Research

Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants: Fighting the Fire Within

Wayne Askew, Ph.D., University of Utah

A fire is smoldering within the cells of your body that could burst into flame at any moment. Scientists who study aging, chronic disease, and preventive medicine call the "smoldering fire free radical production and the "flame oxidative stress. Oxidative stress is the term used to describe the damaging oxidation of biological tissues by free radicals. Free radicals are unstable and short-lived molecules that are especially reactive because they have an unpaired electron in their outer orbit. These molecules seek to stabilize their structure (pair the electrons in their outer orbit) by stealing an electron from an unsuspecting neighbor (Figure 1). When this happens, the free radical is stable once again. The molecule that lost an electron may quit functioning or become a free radical itself.

Figure 1—Free radical damage, (reprinted with

permission of Andrew Subudhi).

Oxygen molecules within the body are essential for life. However, a small percentage of these oxygen molecules can become damaging reactive oxygen species or free radicals. Since humans must exist in an atmosphere of oxygen and consume large quantities to survive, they have developed very effective antioxidant defense systems to neutralize these free radicals. A certain amount of free radical formation is a normal part of metabolism. Our antioxidant defense systems usually prevent free radicals from causing excessive damage. Factors that increase oxidative stress include high levels of energy expenditure, exposure to sunlight and oxidative pollutants, and inadequate dietary intake of antioxidants.

The good news is that the human body is remarkably well equipped to minimize oxidative stress caused by free radical damage. We must provide the body with the "biological flame retardants or antioxidant nutrients it needs to neutralize free radicals. Antioxidant nutrients can be minerals, vitamins, or plant phytochemicals. The minerals zinc, selenium, magnesium, and manganese function as important nutrient cofactors or "helpers for antioxidant enzymes. These minerals and enzymes work together to neutralize free radicals. Left unchecked, free radicals can strip electrons from unsuspecting neighbors, leading to leaky cell membranes, nonfunctional enzyme proteins, and even coding errors in DNA molecules. Antioxidant enzymes are fast acting and very effective as long as the level of invading free radicals is not excessive. When severe oxidative stress is present and the antioxidant enzymes are overwhelmed by the invading free radicals, the antioxidant vitamins and antioxidant phytochemicals become the last line of defense between our cells and free radical damage.

Some antioxidant vitamins such as vitamin E (a-tocopherol) and vitamin C (ascorbate) act as "tag team partners to intercept and neutralize free radicals. Vitamin E is lipid (fat) soluble and can position itself in the membrane of cells and lipoproteins where it intercepts free radicals that attack cell membranes. Once vitamin E has intercepted a free radical, it can pass the task on to water-soluble vitamin C. In this manner, vitamin C regenerates the immobile vitamin E in the membrane and can, in turn, be regenerated by other antioxidant phytochemicals in the cell or pass out of the cell to be excreted in the urine.

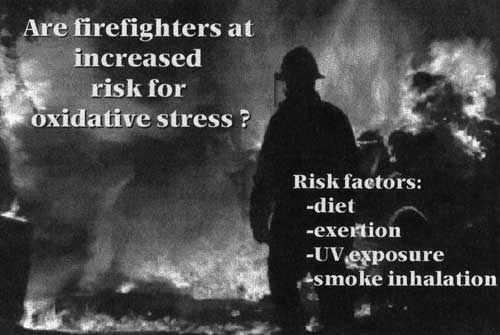

Wildland firefighters expend large quantities of energy, are exposed to sunlight, work in an environment that contains pollutants from burning vegetative material, and often alter their dietary patterns while fighting fires.

Phytochemicals are molecules of plant origin consumed in the diet that are not true vitamins, but that can be very potent antioxidant nutrients. We gain the protective effect of these powerful antioxidant phytochemicals when we consume fruits and vegetables. Five servings of fruits and vegetables per day supply us with enough of these antioxidants to prevent or combat many chronic diseases such as cancer and macular degeneration.

Active people working in remote outdoor environments usually do not have access to ample quantities of fresh fruits and vegetables. In fact, Askew has found these individuals do not even consume the recommended five servings of fruits and vegetables per day when they are eating at home.

How can we tell if someone is experiencing excessive oxidative stress? Free radicals leave a trail of cellular damage—fragments of damaged lipids, proteins, and DNA. We can look for these "damage indicator fragments in breath, blood, and urine. Bioindicators of oxidative stress can be used to establish the need for additional dietary antioxidants as well as the optimal intake of these antioxidants. Elevated levels of oxidative stress usually mean that the body needs reinforcements in its battle against free radicals. These "reinforcements are usually dietary antioxidants that can come from food or antioxidant supplements.

Wildland firefighters expend large quantities of energy, are exposed to sunlight, work in an environment that contains pollutants from burning vegetative material, and often alter their dietary patterns while fighting fires. Research involving occupational groups that share these oxidative-stress risk factors leads us to predict that firefighters may also experience increased free radical formation. Therefore, firefighters might benefit from antioxidant supplementation. Certain types of military training are similar to the rigors of wildland firefighting. Preliminary studies of U.S. Army Ranger training and U.S. Marine Mountain Warfare training indicate that trainees may be under increased levels of oxidative stress and might benefit from supplemental antioxidants.

Research is needed to establish firefighter exposure to oxidative stress and to investigate firefighters' response to supplemental antioxidants. Until then, it is advisable to take a cautious and conservative approach that includes both diet and exercise as preventive measures. The Forest Service has recognized that physical fitness and diet are important components of maintaining firefighter health and safety. As recommended in the Forest Service manual Fitness and Work Capacity (NFES 1596), firefighters should be in excellent physical condition, participate in regular aerobic and strength training, and pay close attention to their diet to ensure that they have high levels of antioxidant defense enzymes and nutrients in their tissues.

The diet should include at least five servings of fruits and vegetables each day. During extended periods of training or actual firefighting, the catering service should be encouraged to supply foods that contain high levels of antioxidant nutrients. Fruits, fruit juices, and vegetable juices are appealing to most people even under adverse field conditions, and they are good sources of antioxidant nutrients.

Oxidative stress causes tissue damage, slows recovery from fatigue, and contributes to long-term health problems (heart disease, cancer, cataracts).

Consideration should be given to providing supplemental antioxidants during field training and firefighting. These supplements could be provided in beverage, solid (energy bar), or tablet form.

Dr. Askew is Professor and Director of the Department of Food and Nutrition at the University of Utah. He served many years as a researcher at the U.S. Army Research Institute for Environmental Medicine. He continues to conduct field research on military populations such as Army Rangers and Marines. The complete text of this paper can be found in Wildland Firefighter Health and Safety: Recommendations of the April 1999 Conference (9951-2841-MTDC).