Design Strategies That Work for Forest Service LEED Buildings

Some Forest Service Regions have staff architects and engineers who design some or most of their new buildings, but most Forest Service building designs are done by architectural and engineering contractors. Whether a design is done in house or by a contractor, certain design methods and procedures lead to a more successful outcome. Most importantly, the design team must consider LEED certification a means to achieve better, more sustainable buildings, rather than viewing "getting LEED Silver" as an isolated goal to be added to ordinary design and construction practices.

What Line Officers Need To Know

Focus on durable and energy-efficient LEED strategies to maximize cost effectiveness over the life of the building. With better insulation, more efficient lighting and HVAC systems, and finishes and systems that last longer, buildings will have lower operations and maintenance costs. The savings will benefit the unit's budget and occupants will be more comfortable.

Building Performance Goals

Before design can begin, the facility's function, general appearance, and budget must be established. This information should be developed and recorded in a project prospectus. More information about creating and using a project prospectus is available at http://www.fs.fed.us/eng/toolbox/fmp/fmp08.htm. In addition to the information that's required in all Forest Service prospectuses, those for LEED buildings should clearly state that the building must be LEED certified and at which level. In addition, the prospectus should contain the LEED and sustainability requirements in Forest Service Handbook 7309.11, chapter 70 (http://www.fs.fed.us/im/directives/fsh/7309.11/7309.11_70.doc).

It's a good idea to include information about the LEED strategies that are deemed most appropriate for the particular project in the final project prospectus. This information will guide the design process and save design and review time that might otherwise be wasted by false starts or inappropriate conceptual designs.

A table has been developed using data from 19 Forest Service offices across the country that shows which LEED credits can most likely be incorporated into Forest Service building designs cost effectively. The table also includes information about which specific sustainable strategies are required for Forest Service buildings. See the "LEED Prerequisites and Points for Forest Service Offices" table in appendix A. Of course, not every Forest Service building should incorporate the same LEED strategies, because climate and building function vary significantly. The table can be modified for individual projects to show which LEED credits will be required or encouraged and which are not likely to be practical.

Integrated Design

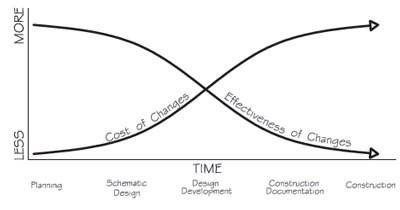

The most successful LEED designs begin incorporating LEED considerations during the planning stage. Doing so makes achieving LEED much easier and more cost effective than if LEED features are pasted into a design that has mostly been completed (figure 5).

Figure 5—The best time to incorporate nonstandard design

elements is at

the planning stage. Early in the design process,

all options are open. Incorporating

changes from standard

practices becomes increasingly ineffective and expensive

as

the design becomes more complete.

Click here for long description.

The most effective way to incorporate LEED considerations early in the design process is to use an integrated design approach. Integrated design—a radical departure from the traditional planning and design process—is required by the USDA Sustainable Buildings Implementation Plan (http://www.usda.gov/energyandenvironment/facilities/sbip.htm) and Forest Service Handbook 7309.11, chapter 70 (http://www.fs.fed.us/im/directives/fsh/7309.11/7309.11_70.doc).

During the traditional planning and design process, the owner and each design specialist make decisions in relative isolation from each other. The owner decides the building's size and location, the budget, and the major functions, hires an architect, and usually tells the architect the general style that is preferred. The architect determines the building layout and tries to make the esthetics please the owner. The architect turns the plans over to the structural engineer, who inserts a structure into the architect's layout and esthetic vision. Then the plans are shipped to the mechanical and electrical engineers, who add heating, cooling, lighting, and electrical systems. Next, the landscape architect is engaged to add plantings and other amenities to the outside of the building. A civil engineer may be hired to design parking areas and access roads. A construction contractor is hired and the structure is built to match the plans.

This process often leads to conflicts, inefficiencies, redesigns, and change orders. Structural, mechanical, and electrical engineers compete for limited space and struggle to design systems that will compensate for incompatible or interfering design decisions by other design specialists. Contractors sometimes balk at details that don't match their preferred methods of construction and may have difficulty integrating the separately designed systems.

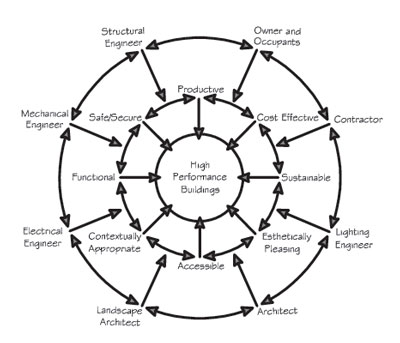

Integrated design (figure 6) is a team approach. The building owner still controls the budget and has the final say, but the owner, architect, engineers, landscape architect, building occupants, and sometimes the contractor and building commissioner collaborate on design choices. They discuss the effects of design choices on building functions and components throughout the design process, beginning with the planning stage. Each team member has different expertise and may devote more or less time to the effort, but each member is integral to the design team.

Figure 6—This graphic representation of the integrated design

process shows

how all members of the design team collaborate

on each of the design goals

to produce high-performance buildings.

Click here for the long description.

Using an integrated design process, more time is invested in the planning and conceptual stages of the process with less time spent on design. All of the building's features and systems work together more efficiently and cost effectively. If cost-effective LEED design is important to a project, hire a design firm that routinely uses an integrated design process.

To illustrate the importance of integrated design, consider the initial and long-term costs of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) and electrical systems. Site orientation (landscape architect), building configuration and envelope (architect), and light fixture and daylighting choices (lighting engineer) have bigger effects on the costs of electrical and HVAC systems than the mechanical and electrical engineers' choices of mechanical and electrical systems (figure 7). More efficient buildings that work with the local climate and are configured to allow nonglare daylight to penetrate well into the building need smaller HVAC systems and use less fuel and electricity.

Figure 7—This graphic representation shows the relative

amount of influence

on long-term energy costs attributable to

choices by different design disciplines.

Design decisions made

by the landscape architect and architect (base of pyramid)

have the most effect. Design choices made by the lighting

engineer (middle

tier of pyramid) also have a substantial effect.

The mechanical and electrical

systems specified by the mechanical

and electrical engineers (top tier of pyramid)

have less influence

on long-term costs than the other design decisions.

Click here for the long description.

The "Whole Building Design Guide" (http://www.wbdg.org/wbdg_approach.php) explains more about integrated design. The American Institute of Architects encourages including the contractor in the integrated design process, which they call "integrated project delivery" (http://www.aia.org/index.htm, search for "collaboration: integrated" and click on "WORDS BY: The Key Is Collaboration: Integrated Project Delivery").