Sclerocactus papyracanthus

Table of Contents

|

|

|

| Paperspine fishhook cactus. Image by Rebou at the German language Wikipedia. |

Introductory

SPECIES: Sclerocactus papyracanthus

AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION :

Matthews, Robin F. 1994. Sclerocactus papyracanthus. In: Fire Effects

Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service,

Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer).

Available: Available: https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/cactus/sclpap/all.html

[].

Revisions:

On 20 March 2018, the common and scientific names of this species were changed in FEIS

from: Pediocactus papyracanthus, grama-grass cactus

to: Sclerocactus papyracanthus, paperspine fishhook cactus. Images were also added.

ABBREVIATION :

SCLPAP

SYNONYMS :

Pediocactus papyracanthus (Engelmann) L. Benson (Cactaceae) [2,17,18]

Toumeya papyracanthus (Engelm.) Britt. & Rose [4,8,17]

NRCS PLANT CODE :

SCPA10

COMMON NAMES :

paperspined cactus

grama-grass cactus

toumeya

TAXONOMY :

The scientific name of paperspine fishhook cactus is Sclerocactus papyracanthus

(Engelm.) N.P. Taylor (Cactaceae) [16].

LIFE FORM :

Cactus

FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS :

None

OTHER STATUS :

Paperspine fishhook cactus has only 6 to 20 occurrences globally and is

imperiled and vulnerable to extinction throughout its range. It is on

the Texas Natural Heritage Program's Special Plant List and is

critically imperiled and vulnerable to extirpation from Texas [13].

DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE

SPECIES: Sclerocactus papyracanthus

GENERAL DISTRIBUTION :

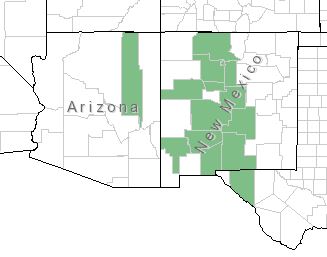

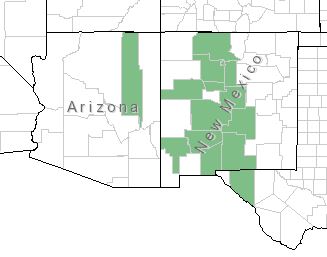

Paperspine fishhook cactus is found in the southern portion of Navajo County,

Arizona, and from southeast Rio Arriba County and McKinley County to

Grant and Dona Ana counties in New Mexico [1,2]. Additional populations

have been located in Hudspeth County, Texas [1,13]. Paperspine fishhook cactus

is inconspicuous and probably irregular in occurrence; it may be more

widespread than presently known [1,2].

|

| Distribution of paperspine fishhook cactus. Map courtesy of USDA, NRCS. 2018. The PLANTS Database.

National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC [16] [2018, January 29]. |

ECOSYSTEMS :

FRES35 Pinyon - juniper

FRES40 Desert grasslands

STATES :

AZ NM TX

BLM PHYSIOGRAPHIC REGIONS :

7 Lower Basin and Range

12 Colorado Plateau

KUCHLER PLANT ASSOCIATIONS :

K023 Juniper - pinyon woodland

K053 Grama - galleta steppe

K054 Grama - tobosa prairie

SAF COVER TYPES :

220 Rocky Mountain juniper

239 Pinyon - juniper

SRM (RANGELAND) COVER TYPES :

504 Juniper-pinyon pine (Juniperus-Pinus spp.) woodland

735 Sideoats grama-sumac-juniper

|

| Paperspine fishhook cactus habitat. Image by Rebou at the German language Wikipedia |

HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES :

Paperspine fishhook cactus grows in pinyon-juniper woodlands and in desert

grasslands and is almost always associated with grama (Bouteloua spp.),

especially blue grama (B. gracilis) [2,17]. It may also be associated

with dropseed (Sporobolus spp.) [11].

MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

SPECIES: Sclerocactus papyracanthus

IMPORTANCE TO LIVESTOCK AND WILDLIFE :

NO-ENTRY

PALATABILITY :

NO-ENTRY

NUTRITIONAL VALUE :

NO-ENTRY

COVER VALUE :

NO-ENTRY

VALUE FOR REHABILITATION OF DISTURBED SITES :

NO-ENTRY

OTHER USES AND VALUES :

NO-ENTRY

OTHER MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS :

In New Mexico, populations of paperspine fishhook cactus are in decline, some

severely so. However, its highly inconspicuous nature makes it a

difficult species to study. Paperspine fishhook cactus is affected by

disturbances such as urban development, grazing, recreational use of

land, and cactus collection. It was once common on grassy outwash fans

at the western edge of the Sandia Mountains, but that entire area is now

consumed by the eastern expansion of the city of Albuquerque. Both

paperspine fishhook cactus and its habitat are destroyed by heavy off-road

vehicle traffic. Paperspine fishhook cactus populations have often been quickly

depleted by cactus collectors. Fairly tall paperspine fishhook cactus plants

may be common in ungrazed areas, but under moderate grazing intensities

plants are often trampled and taller plants are less frequent. Soil

compaction due to grazing is also a problem since most paperspine fishhook

cactus seedlings are found on loose soil. Light grazing may open the

grass cover and facilitate seedling establishment, whereas more intense

grazing reduces grass cover and exposes paperspine fishhook cactus to increased

predation by small herbivores. Also, the loss of grass cover results in

increased erosion of topsoil and accelerates the loss of potential sites

for seedling establishment [11].

BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS

SPECIES: Sclerocactus papyracanthus

GENERAL BOTANICAL CHARACTERISTICS :

Paperspine fishhook cactus is a native stem succulent with solitary stems 1 to 3

inches (2.5-7.5 cm) tall and 0.4 to 0.8 inch (1-2 cm) in diameter. It

has no ribs and tubercles are elongate. Areoles are 0.04 to 0.06 inch

(0.1-0.15 cm) in diameter and generally 0.12 inch (0.3 cm) apart. The

spines are dense, often obscuring the surface of the stem. The central

spines are up to 1.2 inches (3 cm) long and strongly flattened. Radial

spines lie parallel to the stem surface and are up to 0.12 inch (0.3 cm)

long. Flowers are found on new growth of the current season and are

therefore near the apex of the stem. The fruit is green, often changing

to tan, and is dry at maturity. The fruits are dehiscent along a dorsal

slit and around the circumscissile apex [2,17]. Paperspine fishhook cactus has

fibrous roots that are 2 to 4 inches (5-10 cm) long [4].

RAUNKIAER LIFE FORM :

Stem succulents

REGENERATION PROCESSES :

NO-ENTRY

SITE CHARACTERISTICS :

Paperspine fishhook cactus is restricted to fine, sandy clay loams and red sandy

soils of open flats at 5,000 to 7,200 feet (1,500-2,200 m) elevation

[1,2]. It is often found on highly erodable sites [11]. Paperspine fishhook

cactus grows in or near fairy rings of blue grama, and is inconspicuous

because its spines resemble dried blue grama leaves [2,17].

SUCCESSIONAL STATUS :

NO-ENTRY

SEASONAL DEVELOPMENT :

NO-ENTRY

FIRE ECOLOGY

SPECIES: Sclerocactus papyracanthus

FIRE ECOLOGY OR ADAPTATIONS :

Specific information concerning adaptations that paperspine fishhook cactus may

have for survival following fire is not available in the literature.

Its small stature and the fact that it often occurs in or near clumps of

grama may make it particularly vulnerable to destruction by fire. Paperspine

fishhook cactus may survive fire mainly in refugia.

Thomas [14] cited references suggesting that fire intervals in desert

grasslands may be 3 to 40 years.

FIRE REGIMES:

Find fire regime information for the plant communities in which this

species may occur by entering the species name in the FEIS home page

under "Find Fire Regimes".

POSTFIRE REGENERATION STRATEGY :

NO-ENTRY

FIRE EFFECTS

SPECIES: Sclerocactus papyracanthus

IMMEDIATE FIRE EFFECT ON PLANT :

The immediate effect of fire on paperspine fishhook cactus is unknown [15].

Paperspine fishhook cactus is probably killed by even light fires.

Succulents in general rarely actually burn, but spines may ignite and

flames are then carried to the apex. The cactus body may scorch and

blister without pyrolysis. The primary cause of mortality is death of

the photosynthetic tissue and underlying phloem and cambium. Cacti may

appear completely scorched with no green tissue visible, yet may survive

fire. However, fire can cause delayed mortality in small succulents

such as paperspine fishhook cactus. Removal of spines by fire also increases

subsequent herbivory [14]. Some succulents survive fire in refugia or

if the litter surrounding them is sparse [5,14].

DISCUSSION AND QUALIFICATION OF FIRE EFFECT :

NO-ENTRY

PLANT RESPONSE TO FIRE :

NO-ENTRY

DISCUSSION AND QUALIFICATION OF PLANT RESPONSE :

NO-ENTRY

FIRE MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS :

REFERENCES

SPECIES: Sclerocactus papyracanthus

REFERENCES :

1. Anon. 1992. Handbook of Arizona's endangered, threatened, and candidate

plants. Summer 1992. [Place of publication unknown]: [Publisher

unknown]. 57 p. On file with: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest

Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory,

Missoula, MT. [20963]

2. Benson, Lyman. 1982. The cacti of the United States and Canada.

Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. 1044 p. [1513]

3. Bernard, Stephen R.; Brown, Kenneth F. 1977. Distribution of mammals,

reptiles, and amphibians by BLM physiographic regions and A.W. Kuchler's

associations for the eleven western states. Tech. Note 301. Denver, CO:

U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. 169 p.

[434]

4. Britton, N. L.; Rose, J. N. 1963. The Cactaceae. Vol. 3. New York: Dover

Publications, Inc. 258 p. [22644]

5. Cable, Dwight R. 1973. Fire effects in southwestern semidesert

grass-shrub communities. In: Proceedings, annual Tall Timbers fire

ecology conference; 1972 June 8-9; Lubbock, TX. Number 12. Tallahassee,

FL: Tall Timbers Research Station: 109-127. [4338]

6. Eyre, F. H., ed. 1980. Forest cover types of the United States and

Canada. Washington, DC: Society of American Foresters. 148 p. [905]

7. Garrison, George A.; Bjugstad, Ardell J.; Duncan, Don A.; [and others].

1977. Vegetation and environmental features of forest and range

ecosystems. Agric. Handb. 475. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service. 68 p. [998]

8. Kearney, Thomas H.; Peebles, Robert H.; Howell, John Thomas; McClintock,

Elizabeth. 1960. Arizona flora. 2d ed. Berkeley, CA: University of

California Press. 1085 p. [6563]

9. Kuchler, A. W. 1964. Manual to accompany the map of potential vegetation

of the conterminous United States. Special Publication No. 36. New York:

American Geographical Society. 77 p. [1384]

10. Raunkiaer, C. 1934. The life forms of plants and statistical plant

geography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 632 p. [2843]

11. Spellenberg, Richard. 1993. Species of special concern. In: Dick-Peddie,

William A., ed. New Mexico vegetation: Past, present, and future.

Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press: 179-224. [21101]

12. Stickney, Peter F. 1989. Seral origin of species originating in northern

Rocky Mountain forests. Unpublished draft on file at: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire

Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT; RWU 4403 files. 7 p. [20090]

13. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. 1992. Special plant list: January

31, 1992. Austin, TX: Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Texas Natural

Heritage Program. 29 p. [20507]

14. Thomas, P. A. 1991. Response of succulents to fire: a review.

International Journal of Wildland Fire. 1(1): 11-22. [14991]

15. Thomas, P. A.; Goodson, P. 1992. Conservation of succulents in desert

grasslands managed by fire. Biological Conservation. 60(2): 91-100.

[19894]

16. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2018. PLANTS Database, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service

(Producer). Available: https://plants.usda.gov [34262]

17. Weniger, D. 1970. Cacti of the Southwest. Austin, TX: University of

Texas Press. 249 p. [22645]

18. Arp, Gerald. 1972. A revision of Pediocactus. Cactus & Succulent

Journal. 44(5): 218-222. [22646]

FEIS Home Page