Index of Species Information

|

|

|

| Mountain woodsorrel. Creative Commons image by Jason Hollinger. |

Introductory

SPECIES: Oxalis montana

AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION:

Pavek, Diane S. 1992. Oxalis montana. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station,

Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available:

https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/forb/oxamon/all.html [].

Revisions:

On 1 June 2018, the common name of this species was changed in FEIS

from: common woodsorrel

to: mountain woodsorrel. Images were also added.

ABBREVIATION:

OXAMON

SYNONYMS:

Oxalis acetosella L.

Oxalis acetosella f. montana Raf.

Oxalis acetosella var. rhodantha (Fern.) Knuth.

NRCS PLANT CODE:

OXMO

COMMON NAMES:

mountain woodsorrel

common woodsorrel

white woodsorrel

wood shamrock

TAXONOMY:

The scientific name of mountain woodsorrel is Oxalis montana Raf.,

in the woodsorrel family (Oxalidaceae). There are no recognized

subspecies or varieties. Mountain woodsorrel is closely related to the

European species Oxalis acetosella. Some earlier authors included

mountain woodsorrel as a variety of O. acetosella [10]. Two forms

based on flower color are infrequently used [10]:

Oxalis montana forma montana

Oxalis montana forma rhodantha Fern.

LIFE FORM:

Forb

FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS:

No special status

OTHER STATUS:

NO-ENTRY

DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE

SPECIES: Oxalis montana

GENERAL DISTRIBUTION:

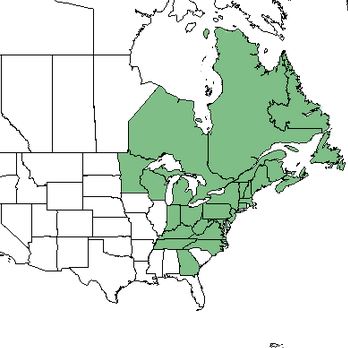

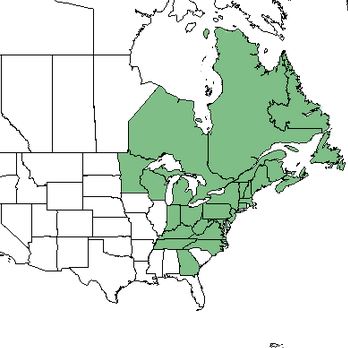

In Canada, mountain woodsorrel occurs from Manitoba east to southern

Labrador and south to Nova Scotia [32]. In the United States, its range

extends from Minnesota across the North Central States to New England

[22]. Its range continues south along the Appalachian Mountains to

North Carolina and Tennessee [10,22].

|

| Distribution of mountain woodsorrel. Map courtesy of USDA, NRCS. 2018. The PLANTS Database.

National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC [2018, June 1] [40]. |

ECOSYSTEMS:

FRES11 Spruce - fir

FRES14 Oak - pine

FRES15 Oak - hickory

FRES18 Maple - beech - birch

FRES19 Aspen - birch

FRES23 Fir - spruce

STATES:

CT DE IL IN KY ME MD MA MI MN

NH NJ NY NC OH PA RI TN VA WV

WI MB NF NS ON

BLM PHYSIOGRAPHIC REGIONS:

NO-ENTRY

KUCHLER PLANT ASSOCIATIONS:

K096 Northeastern spruce - fir forest

K097 Southeastern spruce - fir forest

K102 Beech - maple forest

K104 Appalachian oak forest

K106 Northern hardwoods

K107 Northern hardwoods - fir forest

K108 Northern hardwoods - spruce forest

SAF COVER TYPES:

1 Jack pine

5 Balsam fir

12 Black spruce

13 Black spruce - tamarack

15 Red pine

16 Aspen

17 Pin cherry

18 Paper birch

19 Gray birch - red maple

21 Eastern white pine

22 White pine - hemlock

23 Eastern hemlock

24 Hemlock - yellow birch

25 Sugar maple - beech - yellow birch

28 Black cherry - maple

30 Red spruce - yellow birch

31 Red spruce - sugar maple - beech

32 Red spruce

33 Red spruce - balsam fir

34 Red spruce - Fraser fir

35 Paper birch - red spruce - balsam fir

37 Northern white-cedar

60 Beech - sugar maple

107 White spruce

SRM (RANGELAND) COVER TYPES:

NO-ENTRY

HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES:

Mountain woodsorrel is a dominant understory species in red spruce (Picea

rubens) and balsam or Fraser fir (Abies balsamea or A. fraseri) forests

of the Appalachian Mountains, which are part of the boreal forest

formation [29,34]. Mountain woodsorrel is an indicator for several forest

habitat types or site types in the balsam and Fraser fir phases

[3,5,11,15].

Mountain woodsorrel is dominant in the northern hardwoods forest, red or

sugar maple-yellow birch-American beech (Acer rubrum or A.

saccharum-Betula lutea-Fagus grandifolia) [7,24]. It is also a dominant

species in the transition plant associations between the boreal forest

and the northern hardwoods [19,37]. It is a minor component of the

riparian communities in the northern hardwood forests [6].

Mountain woodsorrel is subdominant in seral communities of black cherry

(Prunus serotina)-red maple [36]. In northern Wisconsin, mountain

woodsorrel is a dominant forb in the association of eastern

hemlock-false lily-of-the-valley-goldthread (Tsuga

canadensis-Maianthemum canadense-Coptis groenlandica) [13,20]. In white

cedar (Thuja occidentalis) communities, mountain woodsorrel is a minor

component with a corresponding low importance value of 0.4 [28].

Frequent herbaceous codominants are false lily-of-the-valley,

goldthread, starflower (Trientalis borealis), and woodferns (Dryopteris

spp.) [8,29,31,37,41].

Publications that list mountain woodsorrel as a dominant herb are:

(1) Field Guide: Habitat classification system for Upper Peninsula of

Michigan and northeast Wisconsin [4]

(2) Ground vegetation patterns of the spruce-fir area of the Great Smoky

Mountains National Park [5]

(3) The principal plant associations of the Saint Lawrence Valley [7]

(4) Field guide to forest habitat types of northern Wisconsin [20]

(5) Habitat classification system for northern Wisconsin [21]

(6) Soil-vegetation relationships in northern hardwoods of Quebec [24]

(7) A comparison of virgin spruce-fir forest in the northern and southern

Appalachian system [29]

(8) Vegetation, soil, and climate on the Green Mountains of Vermont [34]

(9) Communities and tree seedling distribution in Quercus rubra- and Prunus

serotina- dominated forests in southwestern Pennsylvania [36].

MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

SPECIES: Oxalis montana

IMPORTANCE TO LIVESTOCK AND WILDLIFE:

While mountain woodsorrel has not been investigated, other members of the

woodsorrel family (Oxalis pes-capre and O. corniculata) form

concentrations of soluble oxalates lethal to livestock under specific

grazing conditions [18].

PALATABILITY:

No information was available on this topic.

NUTRITIONAL VALUE:

No information was available on this topic.

COVER VALUE:

No information was available on this topic.

VALUE FOR REHABILITATION OF DISTURBED SITES:

Mountain woodsorrel is a soil stabilizer; it has extensive clonal growth

and the ability to grow on steep ground, poor soil, and in deep shade

[5,27,38,39].

In a Canadian northern hardwood-boreal transition forest, disturbed

ground was mulched to suppress red raspberry (Rubus idaeus) growth [16].

Mountain woodsorrel appeared during the second growing season, despite the

oat (Avena sativa) mulch. Because only plants with 10 percent or

greater cover were recorded, it is likely that mountain woodsorrel was

present the first year in low amounts [16].

OTHER USES AND VALUES:

No information was available on this topic.

OTHER MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

No information was available on this topic.

BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS

SPECIES: Oxalis montana

GENERAL BOTANICAL CHARACTERISTICS:

Mountain woodsorrel is a native woodland perennial with well-developed

clonal growth [1]. It is a small evergreen plant (less than 4 inches

[10 cm] high) that has scaley rhizomes [23]. Mountain woodsorrel does not

have a main stem. Leaves, with three cloverlike leaflets, are basal.

The fruit is a round capsule [10,32].

RAUNKIAER LIFE FORM:

Geophyte

REGENERATION PROCESSES:

Reproduction usually involves episodes of seedling recruitment as a

result of disturbance, such as fire and logging, followed by long

periods of vegetative clonal growth [1]. Mountain woodsorrel forms

extensive colonies in boreal spruce-fir forests; however, its colonies

rarely exceed several feet in diameter in the northern hardwood forests

[35].

Mountain woodsorrel reproduces both sexually and asexually. Asexual

flowers (cleistogamous) produce greater amounts of seed compared to

sexual flowers [14]. Total fruit set per plant is low because there is

only one flower per stalk, with a recorded maximum of 34 flowers per

plant [1]. Mature capsules dehisce seeds forcefully, flinging them

outward from the plant [14].

SITE CHARACTERISTICS:

Mountain woodsorrel has wide ecologic amplitude and occurs commonly

throughout the northern hardwood and spruce-fir (Picea rubens-Abies

balsamea) forests of the Appalachian Mountains [35]. Some authors have

stated that mountain woodsorrel occurrence is not correlated with any

particular suite of site features [27,35].

Mountain woodsorrel is on the glaciated uplands of the Canadian shield

[24]. The shallow soils are sandy loams to loamy tills [20]. Saturated

soils may be poor to moderately well-drained [6,7]. However, soils are

generally poorly developed and often consist only of an organic mat on

top of bedrock [27,31]. Soil pH is strongly to moderately acidic

[15,34,38]. Mountain woodsorrel occurs on level to steep slopes and any

aspect [5]. Plants occur at 500 feet (152 m) in Maine coastal forests

to 5,000 feet (1,524 m) in the Smoky Mountains of Tennessee [24,34,37].

The growing season throughout its range is from 110 to 140 days and is

cool with ample moisture [8]. Snowpack in the subalpine zones can

extend from November to May [31]. The average annual temperatures are

less than 60 degrees Fahrenheit (16 deg C) [41]. Average annual

precipitation is 90 to 140 inches (2,286-3,556 mm) per year [5]. The

moisture regime is perhumid to humid [31]. Rainfall is equitable in all

summer months. Fog drip from evergreen needles increases precipitation

amounts [34].

Moss coverage can be low to high, and very high fern coverage reduces

mountain woodsorrel populations [5]. Associated understory species

include lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium), witherod (Viburnum

cassinoides), hobblebush (Viburnum alnifolium), and bunchberry (Cornus

canadensis) [5,8,15]. Overstory species also include white ash

(Fraxinus americana) and paper birch (Betula papyrifera) [31].

SUCCESSIONAL STATUS:

Mountain woodsorrel is a climax understory species. It is a tolerant

species under mature fir canopy [38,39]. Mountain woodsorrel is present

in, although not characteristic of, early or mid- seral stages in New

England's northern hardwood or spruce-fir boreal forests [35].

Disturbance occurs as severe winds, hurricanes, and fire [31].

SEASONAL DEVELOPMENT:

Plant growth mainly occurs before flowers are out [14]. Sexual flowers

on mountain woodsorrel bloom from late May to August throughout its range

[10,23]. In a population, the flowering period lasts approximately 30

days with individual flowers open for about five days [14]. Fruits

mature in about 12 days, requiring warm days before dehiscence [14].

Seed is shed from June to September throughout its range [14].

FIRE ECOLOGY

SPECIES: Oxalis montana

FIRE ECOLOGY OR ADAPTATIONS:

Burning conditions are usually poor in the spruce-fir boreal forests in

which mountain woodsorrel grows due to the presence of water throughout

the year [17]. Droughts can make the areas more susceptible to fire.

Fires may occur in the southern boreal forests every 50 to 150 years,

and in the northern boreal forests, fire frequencies are every 100 to

300 years [17].

Mountain woodsorrel fire survival strategy is that of a perennial with

underground rhizomes; surviving rhizomes sprout. However, it often

grows in humus on bedrock in spruce-fir forests [27,31]. The organic

layer does not give much protection from fire. No information was found

about mountain woodsorrel seed surviving fire.

FIRE REGIMES:

Find fire regime information for the plant communities in which this

species may occur by entering the species name in the FEIS home page under

"Find Fire Regimes".

POSTFIRE REGENERATION STRATEGY:

Rhizomatous herb, rhizome in soil

Secondary colonizer - off-site seed

FIRE EFFECTS

SPECIES: Oxalis montana

IMMEDIATE FIRE EFFECT ON PLANT:

No fire studies have been done on mountain woodsorrel . Fire would

top-kill this plant. Growing in mainly organic or shallow soils, its

rhizomes probably would not survive a fire of moderate severity.

DISCUSSION AND QUALIFICATION OF FIRE EFFECT:

NO-ENTRY

PLANT RESPONSE TO FIRE:

Surviving rhizomes will sprout. Existing patches can expand to colonize

open areas. Vegetative reproduction allows the population flexibility

in initiating or stopping plant development. Since mountain woodsorrel

can reproduce by asexual flowers, seed set is highly probable, despite a

possible low initial population size. Dissemination by explosive

dehiscence provides the ability to colonize open disturbed areas. When

open ground has closed with vegetation, mountain woodsorrel colonies will

continue to expand by rhizome growth (see SUCCESSIONAL STATUS).

DISCUSSION AND QUALIFICATION OF PLANT RESPONSE:

The Research Project Summary Effects of surface fires in a mixed red and

eastern white pine stand in Michigan provides information on prescribed

fire and postfire response of plant community species, including mountain

woodsorrel, that was not available when this species review was written.

FIRE MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

No information was available on this topic.

REFERENCES

SPECIES: Oxalis montana

REFERENCES:

1. Raphael, Martin G.; White, Marshall. 1984. Use of snags by

cavity-nesting birds in the Sierra Nevada. Wildlife Monographs No. 86.

Washington, DC: The Wildlife Society. 66 p. [15592]

2. Bernard, Stephen R.; Brown, Kenneth F. 1977. Distribution of mammals,

reptiles, and amphibians by BLM physiographic regions and A.W. Kuchler's

associations for the eleven western states. Tech. Note 301. Denver, CO:

U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. 169 p.

[434]

3. Blum, Barton M. 1990. Picea rubens Sarg. red spruce. In: Burns, Russell

M.; Honkala, Barbara H., technical coordinators. Silvics of North

America. Volume 1. Conifers. Agric. Handb. 654. Washington, DC: U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: 250-259. [13388]

4. Coffman, Michael S.; Alyanak, Edward; Resovsky, Richard. 1980. Field

guide habitat classification system: For Upper Peninsula of Michigan and

northeast Wisconsin. [Place of publication unknown]: Cooperative

Research on Forest Soils. 112 p. [8997]

5. Crandall, Dorothy L. 1958. Ground vegetation patterns of the spruce-fir

area of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Ecological Monographs.

28(4): 337-360. [11226]

6. Cronan, Christopher S.; DesMeules, Marc R. 1985. A comparison of

vegetative cover and tree community structure in three forested

Adirondack watersheds. Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 15: 881-889.

[7296]

7. Dansereau, Pierre. 1959. The principal plant associations of the Saint

Lawrence Valley. No. 75. Montreal, Canada: Contrib. Inst. Bot. Univ.

Montreal. 147 p. [8925]

8. Davis, Ronald B. 1966. Spruce-fir forests of the coast of Maine.

Ecological Monographs. 36(2): 79-94. [8228]

9. Eyre, F. H., ed. 1980. Forest cover types of the United States and

Canada. Washington, DC: Society of American Foresters. 148 p. [905]

10. Fernald, Merritt Lyndon. 1950. Gray's manual of botany. [Corrections

supplied by R. C. Rollins]. Portland, OR: Dioscorides Press. 1632 p.

(Dudley, Theodore R., gen. ed.; Biosystematics, Floristic & Phylogeny

Series; vol. 2). [14935]

11. Frank, Robert M. 1990. Abies balsamea (L.) Mill. balsam fir. In: Burns,

Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H., technical coordinators. Silvics of

North America. Volume 1. Conifers. Agric. Handb. 654. Washington, DC:

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: 26-35. [13365]

12. Garrison, George A.; Bjugstad, Ardell J.; Duncan, Don A.; [and others].

1977. Vegetation and environmental features of forest and range

ecosystems. Agric. Handb. 475. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service. 68 p. [998]

13. Godman, R. M.; Lancaster, Kenneth. 1990. Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carr.

eastern hemlock. In: Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H., technical

coordinators. Silvics of North America. Volume 1. Conifers. Agric.

Handb. 654. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest

Service: 604-612. [13421]

14. Helenurm, Kaius; Barrett, Spencer C. H. 1987. The reproductive biology

of boreal forest herbs. II. Phenology of flowering and fruiting.

Canadian Journal of Botany. 65: 2047-2056. [6623]

15. Hughes, Jeffrey W.; Fahey, Timothy J. 1991. Colonization dynamics of

herbs and shrubs in disturbed northern hardwood forest. Journal of

Ecology. 79: 605-616. [17724]

16. Jobidon, R.; Thibault, J. R.; Fortin, J. A. 1989. Phytotoxic effect of

barley, oat, and wheat-straw mulches in eastern Quebec forest

plantations 1. Effects on red raspberry (Rubus idaeus). Forest Ecology

and Management. 29: 277-294. [9899]

17. Keeley, Jon E. 1981. Reproductive cycles and fire regimes. In: Mooney,

H. A.; Bonnicksen, T. M.; Christensen, N. L.; [and others], technical

coordinators. Fire regimes and ecosystem properties: Proceedings of the

conference; 1978 December 11-15; Honolulu, HI. Gen. Tech. Rep. WO-26.

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: 231-277.

[4395]

18. Kingsbury, John M. 1964. Poisonous plants of the United States and

Canada. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc. 626 p. [122]

19. Kirkland, Gordon L., Jr. 1977. Responses of small mammals to the

clearcutting of northern Appalachian forests. Journal of Mammalogy.

58(4): 600-609. [14455]

20. Kotar, John; Kovach, Joseph A.; Locey, Craig T. 1988. Field guide to

forest habitat types of northern Wisconsin. Madison, WI: University of

Wisconsin, Department of Forestry; Wisconsin Department of Natural

Resources. 217 p. [11510]

21. Kotar, John; Kovack, Joseph; Locey, Craig. 1989. Habitat classification

system for northern Wisconsin. In: Ferguson, Dennis E.; Morgan,

Penelope; Johnson, Frederic D., eds. Proceedings--Land classifications

based on vegetation applications for resource management; 1987 November

17-19; Moscow, ID. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-257. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department

of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station: 304-306.

[6962]

22. Kuchler, A. W. 1964. Manual to accompany the map of potential vegetation

of the conterminous United States. Special Publication No. 36. New York:

American Geographical Society. 77 p. [1384]

23. Lakela, O. 1965. A flora of northeastern Minnesota. Minneapolis, MN:

University of Minnesota Press. 541 p. [18142]

24. Lemieux, G. J. 1963. Soil-vegetation relationships in northern hardwoods

of Quebec. In: Forest-soil relationships in North America. Corvallis,

OR: Oregon State University Press: 163-176. [8874]

25. Lyon, L. Jack; Stickney, Peter F. 1976. Early vegetal succession

following large northern Rocky Mountain wildfires. In: Proceedings, Tall

Timbers fire ecology conference and Intermountain Fire Research Council

fire and land management symposium; 1974 October 8-10; Missoula, MT. No.

14. Tallahassee, FL: Tall Timbers Research Station: 355-373. [1496]

26. Maguire, D. A.; Forman, R. T. 1983. Herb cover effects on tree seedling

patterns in a mature hemlock-hardwood forest. Ecology. 64(6): 1367-1380.

[9620]

27. McIntosh, R. P.; Hurley, R. T. 1964. The spruce-fir forest of the

Catskill Mountains. Ecology. 45(2): 314-326. [14886]

28. Ohmann, Lewis F.; Ream, Robert R. 1971. Wilderness ecology: virgin plant

communities of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area. Res. Pap. NC-63. St.

Paul, MN: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central

Forest Experiment Station. 55 p. [9271]

29. Oosting, H. J.; Billings, W. D. 1951. A comparison of virgin spruce-fir

forest in the northern and southern Appalachian system. Ecology. 32(1):

84-103. [11236]

30. Raunkiaer, C. 1934. The life forms of plants and statistical plant

geography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 632 p. [2843]

31. Reiners, William A,; Lang, Gerald E. 1979. Vegetational patterns and

processes in the balsam fir zone, White Mountains, New Hampshire.

Ecology. 60(2): 403-417. [14869]

32. Roland, A. E.; Smith, E. C. 1969. The flora of Nova Scotia. Halifax, NS:

Nova Scotia Museum. 746 p. [13158]

33. Scoggan, H. J. 1978. The flora of Canada. Ottawa, Canada: National

Museums of Canada. (4 volumes). [18143]

34. Siccama, T. G. 1974. Vegetation, soil, and climate on the Green

Mountains of Vermont. Ecological Monographs. 44: 325-249. [6859]

35. Siccama, T. G.; Bormann, F. H.; Likens, G. E. 1970. The Hubbard Brook

ecosystem study: productivity, nutrients and phytosociology of the

herbaceous layer. Ecological Monographs. 40(4): 389-402. [8875]

36. Smith, Lisa L.; Vankat, John L. 1991. Communities and tree seedling

distribution in Quercus rubra- and Prunus serotina-dominated forests in

southwestern Pennsylvania. American Midland Naturalist. 126(2): 294-307.

[16876]

37. Spear, Ray W. 1989. Late-Quaternary history of high-elevation vegetation

in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. Ecological Monographs. 59(2):

125-151. [9662]

38. Sprugel, Douglas G. 1976. Dynamic structure of wave-regenerated Abies

balsamea forests in the north-eastern United States. Journal of Ecology.

64: 889-911. [14866]

39. Sprugel, Douglas G. 1981. Natural disturbance and the steady state in

high-altitude balsam fir forest. Science. 211: 390-393. [14870]

40. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2018. PLANTS Database, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service

(Producer). Available: https://plants.usda.gov/. [34262]

41. Webb, William L.; Behrend, Donald F.; Saisorn, Boonruang. 1977. The

effect of logging on songbird populations in a northern hardwood forest.

Wildlife Monographs No. 55. Washington, DC: The Wildlife Society. 35 p.

[13745]

42. Stickney, Peter F. 1989. Seral origin of species originating in northern

Rocky Mountain forests. Unpublished draft on file at: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire

Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT; RWU 4403 files. 7 p. [20090]

FEIS Home Page