Index of Species Information

SPECIES: Fendlera rupicola

|

|

|

| Cliff fendlerbush. Wikimedia Commons image By Andrey Zharkikh from Salt Lake City, UT. |

Introductory

SPECIES: Fendlera rupicola

AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION :

Tesky, Julie L. 1993. Fendlera rupicola. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station,

Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available:

https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/shrub/fenrup/all.html [].

Revisions:

On 6 July 2018, the common name of this species was changed in FEIS

from: fendlerbush

to: cliff fendlerbush. Images were also added.

ABBREVIATION :

FENRUP

SYNONYMS :

Fendlera rupicola var. rupicola

Fendlera rupicola var. falcata Gray, sickle-leaf fendlerbush [12,16,22]

SCS PLANT CODE :

FERU

COMMON NAMES :

cliff fendlerbush

false mockorange

fendlera

fendlerbush

TAXONOMY :

The scientific name of cliff fendlerbush is Fendlera rupicola Gray (Hydrangeaceae) [12,16,20,22,24].

LIFE FORM :

Shrub

FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS :

No special status

OTHER STATUS :

NO-ENTRY

DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE

SPECIES: Fendlera rupicola

GENERAL DISTRIBUTION :

Cliff fendlerbush is found from the Sabinal River to the Pecos River in

scattered locations in Texas. It is common in the higher mountains of

the Trans-Pecos region. It also occurs in the Davis, Chisos, and

Guadalupe mountains; northward and westward into New Mexico, Colorado,

Utah, and Arizona; and southward into Mexico [12,22].

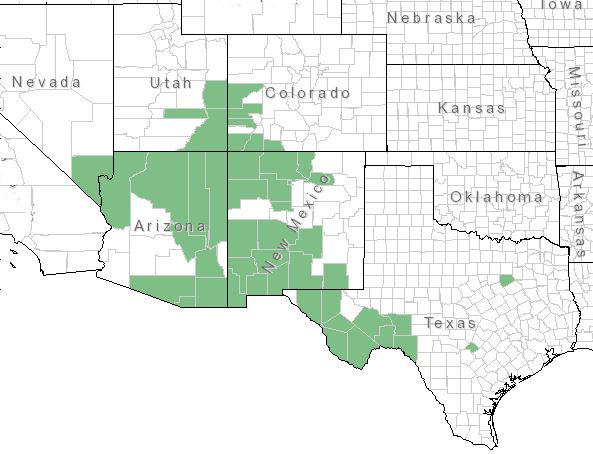

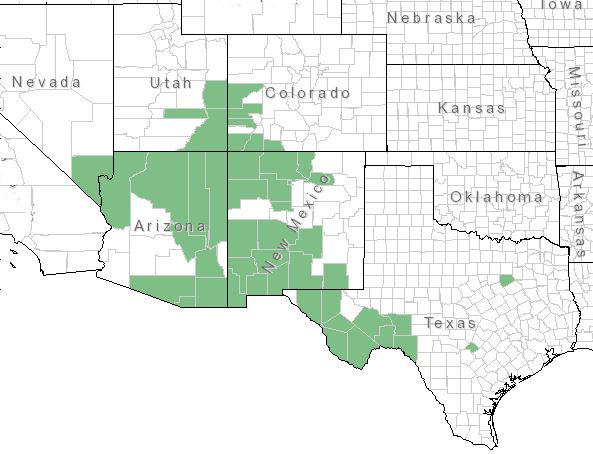

|

| Distribution of cliff fendlerbush in the United States. Map courtesy of USDA, NRCS. 2018. The PLANTS Database.

National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC [2018, July 6] [20]. |

ECOSYSTEMS :

FRES29 Sagebrush

FRES30 Desert shrub

FRES32 Texas savanna

FRES33 Southwestern shrubsteppe

FRES35 Pinyon - juniper

FRES34 Chaparral - mountain shrub

FRES40 Desert grasslands

STATES :

AZ CO NM TX UT MEXICO

BLM PHYSIOGRAPHIC REGIONS :

7 Lower Basin and Range

12 Colorado Plateau

13 Rocky Mountain Piedmont

KUCHLER PLANT ASSOCIATIONS :

K023 Juniper - pinyon woodland

K024 Juniper steppe woodland

K031 Oak - juniper woodlands

K032 Transition between K031 and K037

K037 Mountain-mahogany - oak scrub

K053 Grama - galleta steppe

K054 Grama - tobosa prairie

K058 Grama - tobosa shrubsteppe

K086 Juniper - oak savanna

SAF COVER TYPES :

238 Western juniper

239 Pinyon - juniper

SRM (RANGELAND) COVER TYPES :

NO-ENTRY

HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES :

Cliff fendlerbush is often found in desert shrub, pinyon-juniper

(Pinus-Juniperus spp.)/mountain shrub and blue grama (Bouteloua

gracilis) communities throughout its range [7,15].

Cliff fendlerbush is often found associated with oneseed juniper (Juniperus

monosperma), alligator juniper (J. deppeana), true pinyon (Pinus

edulis), wavyleaf oak (Quercus undulata), skunkbush sumac (Rhus

trilobata), mountain-mahogany (Cercocarpus breviflorus), and antelope

bitterbrush (Purshia tridentata) [7,15].

MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

SPECIES: Fendlera rupicola

IMPORTANCE TO LIVESTOCK AND WILDLIFE :

Cliff fendlerbush is browsed by goats, deer, bighorn sheep, and cattle [12].

In the San Cayetano Mountains, Arizona, cliff fendlerbush made up 11 percent

of the white-tailed deer diet during the hot, dry season (April- June);

this season appears to be the most critical period of the year for deer

herds in the desert southwest [1,2].

PALATABILITY :

Cliff fendlerbush palatability is high for goats in New Mexico. It is closely

grazed by cattle in central Arizona [21], and is a frequent diet item of

white-tailed deer in the San Cayetano Mountains, Arizona [1,2].

NUTRITIONAL VALUE :

NO-ENTRY

COVER VALUE :

NO-ENTRY

VALUE FOR REHABILITATION OF DISTURBED SITES :

NO-ENTRY

OTHER USES AND VALUES :

Cliff fendlerbush is grown as an ornamental. It is suitable for rock gardens

in well-drained, sunny situations, and has been grown as far north as

New England [4,12,18].

OTHER MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS :

Cliff fendlerbush decreases in response to grazing [25].

Cliff fendlerbush has vesicular-arbuscular endomycorrhizal associations

[6,26]. These fungi increase cliff fendlerbush growth by increasing

phosphorus absorption [26].

BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS

SPECIES: Fendlera rupicola

GENERAL BOTANICAL CHARACTERISTICS :

Cliff fendlerbush is a native, deciduous, widely-branched shrub [12,22,24].

It grows 3 to 9 feet (1-3 m) high [4,12,22,24]. The leaves are thick,

twisted, 0.2 to 1.6 inches (5-40 mm) long and 0.08 to 0.28 inches (2-7

mm) wide [13,24]. The flowers are solitary or two to three together at

the ends of short branches [24]. The fruit is a four-celled capsule

which remains on the plant all year [11,13]. Cliff fendlerbush bark is

shreddy [11]. It generally has deep roots [4]. Cliff fendlerbush can endure

intense heat and considerable drought [21].

RAUNKIAER LIFE FORM :

Phanerophyte

REGENERATION PROCESSES :

Cliff fendlerbush reproduces by seed [4,22]. Commercial production is

accomplished through seed that is stratified at 41 degrees Fahrenheit (5

deg C) for 60 to 90 days [4]. Cliff fendlerbush can also reproduce via branch

cuttings [4,22].

SITE CHARACTERISTICS :

Cliff fendlerbush is commonly found on rocky ledges and steep slopes of cliffs

and canyons at elevations of 3,000 to 7,000 feet (914-2,133 m)

[16,22,23]. Cliff fendlerbush thrives on very dry, well-drained, poor soils

that may be rocky and/or alkaline [4,21,22]. Less than 15 inches (38.1 cm)

of annual precipitation have been measured in its natural habitat [4].

SUCCESSIONAL STATUS :

Cliff fendlerbush occurs in nearly all stages of succession. It is most

common in mid- to late-seral communities. In Mesa Verde National Park,

cliff fendlerbush maximum cover and frequency was not reached until 80 years

after a fire in a pinyon-juniper community. In an adjacent 400-year-old

climax pinyon-juniper stand, cliff fendlerbush cover was only 2 percent;

frequency was 8 percent [7].

SEASONAL DEVELOPMENT :

Cliff fendlerbush generally flowers from March through June, depending on the

location [12,22]. In the Trans-Pecos, Texas, cliff fendlerbush sometimes

flowers through August [16]. Cliff fendlerbush fruits mature in July and

August [22].

FIRE ECOLOGY

SPECIES: Fendlera rupicola

FIRE ECOLOGY OR ADAPTATIONS :

Little information is available regarding cliff fendlerbush fire ecology and

adaptations. Erdman [7] suggested that cliff fendlerbush probably recovers

after fire by sprouting from the root crown. Pinyon-juniper communities

where cliff fendlerbush is commonly found historically burned every 10 to 30

years, which favored dominance by grasses. However, for the last 70

years, heavy livestock grazing has reduced grass competition and fuel,

and shrub cover has increased. This has decreased fire occurrence and

lowered the intensity of fires that do occur [27,28]. On 23 grazed

transects in desert shrub communities where cliff fendlerbush occurs in the

Guadalupe Mountains, New Mexico, shrubs had only 6.4 to 6.6 percent

cover. Bare ground cover was 33.8 to 42.4 percent, and litter cover was

6.1 to 12 percent [25].

POSTFIRE REGENERATION STRATEGY :

Small shrub, adventitious-bud root crown

Secondary colonizer - off-site seed

FIRE REGIMES :

Find fire regime information for the plant communities in

which this species may occur by entering the species name in the

FEIS home page under "Find Fire Regimes".

FIRE EFFECTS

SPECIES: Fendlera rupicola

IMMEDIATE FIRE EFFECT ON PLANT :

Information was not available regarding the immediate effects of fire on

cliff fendlerbush. Cliff fendlerbush is probably top-killed or killed by most fires.

PLANT RESPONSE TO FIRE :

In Mesa Verde National Park, 4 years after a July/August, 1959 natural

fire in a pinyon-juniper community, cliff fendlerbush had no significant

cover. Cliff fendlerbush frequency was 2 percent. Twenty-nine years

following a July fire in a nearby pinyon-juniper community, cliff fendlerbush

made up 1 percent of the cover and had 6 percent frequency. Cliff fendlerbush

maximum cover and frequency was not reached until almost 80 years after

a pinyon-juniper fire in Mesa Verde National Park. At this time

cliff fendlerbush made up 14 percent of the cover and had 48 percent frequency

[7].

FIRE MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS :

NO-ENTRY

REFERENCES

SPECIES: Fendlera rupicola

REFERENCES :

1. Anthony, Robert G. 1976. Influence of drought on diets and numbers of

desert deer. Journal of Wildlife Management. 40(1): 140-144. [11558]

2. Anthony, Robert G.; Smith, Norman S. 1977. Ecological relationships

between mule deer and white-tailed deer in southeastern Arizona.

Ecological Monographs. 47: 255-277. [9890]

3. Bernard, Stephen R.; Brown, Kenneth F. 1977. Distribution of mammals,

reptiles, and amphibians by BLM physiographic regions and A.W. Kuchler's

associations for the eleven western states. Tech. Note 301. Denver, CO:

U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. 169 p.

[434]

4. Borland, Jim. 1989. Fendlera rupicola. American Nurseryman. 169(5): 146.

[21970]

5. Dick-Peddie, W. A.; Moir, W. H. 1970. Vegetation of the Organ Mountains,

New Mexico. Science Series No. 4. Fort Collins, CO: Colorado State

University, Range Science Department. 28 p. [6699]

6. Dittberner, Phillip L.; Olson, Michael R. 1983. The plant information

network (PIN) data base: Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, Utah, and

Wyoming. FWS/OBS-83/86. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior,

Fish and Wildlife Service. 786 p. [806]

7. Erdman, James A. 1970. Pinyon-juniper succession after natural fires on

residual soils of Mesa Verde, Colorado. Brigham Young University Science

Bulletin. Biological Series. 11(2): 1-26. [11987]

8. Eyre, F. H., ed. 1980. Forest cover types of the United States and

Canada. Washington, DC: Society of American Foresters. 148 p. [905]

9. Garrison, George A.; Bjugstad, Ardell J.; Duncan, Don A.; [and others].

1977. Vegetation and environmental features of forest and range

ecosystems. Agric. Handb. 475. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service. 68 p. [998]

10. Goodrich, Sherel. 1985. Utah flora: Saxifragaceae. Great Basin

Naturalist. 45(2): 155-172. [15656]

11. Harrington, H. D. 1964. Manual of the plants of Colorado. 2d ed.

Chicago: The Swallow Press Inc. 666 p. [6851]

12. Kearney, Thomas H.; Peebles, Robert H.; Howell, John Thomas; McClintock,

Elizabeth. 1960. Arizona flora. 2d ed. Berkeley, CA: University of

California Press. 1085 p. [6563]

13. Kelly, George W. 1970. A guide to the woody plants of Colorado. Boulder,

CO: Pruett Publishing Co. 180 p. [6379]

14. Kuchler, A. W. 1964. Manual to accompany the map of potential vegetation

of the conterminous United States. Special Publication No. 36. New York:

American Geographical Society. 77 p. [1384]

15. Pieper, Rex D.; Montoya, James R.; Groce, V. Lynn. 1971. Site

characteristics on pinyon-juniper and blue grama in south-central New

Mexico. Bulletin 573. Las Cruces, NM: New Mexico State University,

Agricultural Experiment Station. 21 p. [4540]

16. Powell, A. Michael. 1988. Trees & shrubs of Trans-Pecos Texas including

Big Bend and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks. Big Bend National Park,

TX: Big Bend Natural History Association. 536 p. [6130]

17. Raunkiaer, C. 1934. The life forms of plants and statistical plant

geography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 632 p. [2843]

18. Steger, Robert E.; Beck, Reldon F. 1973. Range plants as ornamentals.

Journal of Range Management. 26: 72-74. [12038]

19. Stickney, Peter F. 1989. Seral origin of species originating in northern

Rocky Mountain forests. Unpublished draft on file at: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire

Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT; RWU 4403 files. 7 p. [20090]

20. U.S. Department of Agriculture, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service.

2018. PLANTS Database, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural

Resources Conservation Service (Producer). Available: https://plants.usda.gov/.

[34262]

21. Van Dersal, William R. 1938. Native woody plants of the United States,

their erosion-control and wildlife values. Washington, DC: U.S.

Department of Agriculture. 362 p. [4240]

22. Vines, Robert A. 1960. Trees, shrubs, and woody vines of the Southwest.

Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. 1104 p. [7707]

23. Weber, William A. 1987. Colorado flora: western slope. Boulder, CO:

Colorado Associated University Press. 530 p. [7706]

24. Welsh, Stanley L.; Atwood, N. Duane; Goodrich, Sherel; Higgins, Larry

C., eds. 1987. A Utah flora. Great Basin Naturalist Memoir No. 9. Provo,

UT: Brigham Young University. 894 p. [2944]

25. Wester, David B.; Wright, Henry A. 1987. Ordination of vegetation change

Guadalupe Mountains, New Mexico, USA. Vegetatio. 72: 27-33. [11167]

26. Williams, Stephen E.; Aldon, Earl F. 1976. Endomycorrhizal (vesicular

arbuscular) associations of some arid zone shrubs. Southwestern

Naturalist. 20(4): 437-444. [5517]

27. Wright, Henry A.; Bailey, Arthur W. 1982. Fire ecology: United States

and southern Canada. New York: John Wiley & Sons. 501 p. [2620]

28. Leopold, Aldo. 1924. Grass, brush, timber, and fire in southern Arizona.

Journal of Forestry. 22(6): 1-10. [5056]

FEIS Home Page