Index of Species Information

SPECIES: Shepherdia argentea

|

|

|

| Silver buffaloberry. Wikimedia Commons image

by SriMesh, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/

index.php?curid=2667469. |

Introductory

SPECIES: Shepherdia argentea

AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION :

Esser, Lora L. 1995. Shepherdia argentea. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station,

Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available:

https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/shrub/shearg/all.html [].

ABBREVIATION :

SHEARG

SYNONYMS :

NO-ENTRY

SCS PLANT CODE :

SHAR

COMMON NAMES :

silver buffaloberry

buffaloberry

thorny buffaloberry

TAXONOMY :

The currently accepted scientific name of silver buffaloberry is

Shepherdia argentea (Pursh.) Nutt. (Elaeagnaceae) [36,47,71,87]. There

are no recognized infrataxa.

LIFE FORM :

Tree, Shrub

FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS :

No special status

OTHER STATUS :

NO-ENTRY

DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE

SPECIES: Shepherdia argentea

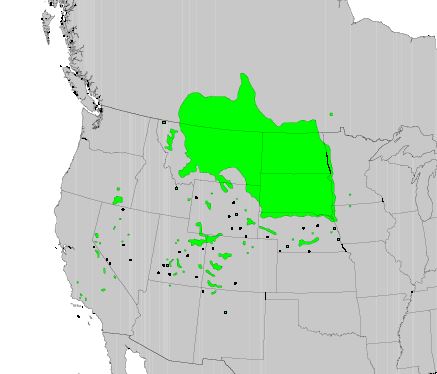

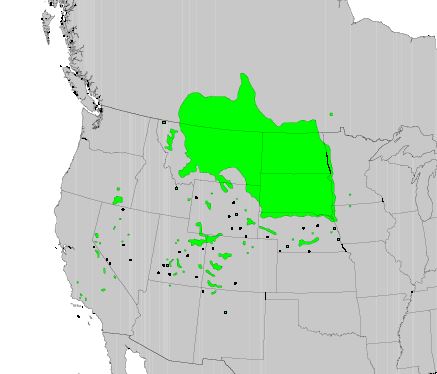

GENERAL DISTRIBUTION :

Silver buffaloberry occurs from British Columbia east to Manitoba and

south to California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Oklahoma [25,44,47,71,87].

Small populations occur in western Minnesota and northwestern Iowa

[25,39]. Silver buffaloberry is most commonly found in the northern

Great Plains [25,44].

|

| Distribution of silver buffaloberry. 1976 USDA, Forest Service map digitized by Thompson and others [89]. |

ECOSYSTEMS :

FRES17 Elm-ash-cottonwood

FRES21 Ponderosa pine

FRES28 Western hardwoods

FRES29 Sagebrush

FRES34 Chaparral-mountain shrub

FRES35 Pinyon-juniper

FRES37 Mountain meadows

FRES38 Plains grasslands

FRES39 Prairie

STATES :

AZ CA CO ID IA KS MN MT NE NV

NM ND OK OR SD UT WA WY AB BC

MB SK

BLM PHYSIOGRAPHIC REGIONS :

2 Cascade Mountains

3 Southern Pacific Border

4 Sierra Mountains

5 Columbia Plateau

6 Upper Basin and Range

8 Northern Rocky Mountains

10 Wyoming Basin

11 Southern Rocky Mountains

12 Colorado Plateau

13 Rocky Mountain Piedmont

14 Great Plains

15 Black Hills Uplift

16 Upper Missouri Basin and Broken Lands

KUCHLER PLANT ASSOCIATIONS :

K011 Western ponderosa forest

K016 Eastern ponderosa forest

K017 Black Hills pine forest

K023 Juniper-pinyon woodland

K037 Mountain-mahogany-oak scrub

K038 Great Basin sagebrush

K056 Wheatgrass-needlegrass shrubsteppe

K064 Grama-needlegrass-wheatgrass

K066 Wheatgrass-needlegrass

K067 Wheatgrass-bluestem-needlegrass

K069 Bluestem-grama prairie

K074 Bluestem prairie

K081 Oak savanna

K098 Northern floodplain forest

SAF COVER TYPES :

63 Cottonwood

217 Aspen

220 Rocky Mountain juniper

235 Cottonwood-willow

236 Bur oak

237 Interior ponderosa pine

239 Pinyon-juniper

247 Jeffrey pine

SRM (RANGELAND) COVER TYPES :

203 Riparian woodland

210 Bitterbrush

310 Needle-and-thread-blue grama

401 Basin big sagebrush

408 Other sagebrush types

411 Aspen woodland

412 Juniper-pinyon woodland

421 Chokecherry-serviceberry-rose

422 Riparian

601 Bluestem prairie

606 Wheatgrass-bluestem-needlegrass

607 Wheatgrass-needlegrass

608 Wheatgrass-grama-needlegrass

612 Sagebrush-grass

615 Wheatgrass-saltgrass-grama

704 Blue grama-western wheatgrass

706 Blue grama-sideoats grama

709 Bluestem-grama

710 Bluestem prairie

714 Grama-bluestem

735 Sideoats grama-sumac-juniper

805 Riparian

HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES :

Silver buffaloberry occurs in a variety of habitats including woodland,

pinyon (Pinus spp.)-juniper (Juniperus spp.), shortgrass prairie,

mixed-grass prairie, shrubland, sagebrush (Artemisia spp.), and riparian

[2,4,11,33,39].

Silver buffaloberry occurs in seral communities throughout the

Intermountain region. It is a riverine floodplain shrub in narrowleaf

cottonwood (Populus angustifolia), black cottonwood (P. trichocarpa),

and willow (Salix spp.) communities of California, Colorado, and Nevada

[2,43,74]. In Colorado silver buffaloberry occurs in a narrowleaf

cottonwood/strapleaf willow (S. ligulifolia)-silver buffaloberry

association [2]. In North Dakota silver buffaloberry is a member of

the quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides)/water birch (Betula

occidentalis) habitat type [29].

In eastern Montana and western North and South Dakota, silver

buffaloberry is an important species in woodland and riparian draws

dominated by green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) [5,12,28,29,55]. Some

common habitat types include green ash, green ash/chokecherry (Prunus

virginiana), and green ash/western snowberry (Symphoricarpos

occidentalis) [5,28,29,37]. In western Montana a silver buffaloberry

community type has been described; western snowberry may form dense

ecotonal thickets around silver buffaloberry stands [28].

Silver buffaloberry is an important species in native shortgrass and

mixed-grass prairies of the northern Great Plains. In North Dakota

silver buffaloberry is commonly found in shrub-grassland communities

dominated by western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), needlegrass (Stipa

spp.), blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), and little bluestem

(Schizachyrium scoparium) [17,45,75]. Silver buffaloberry occurs in

little bluestem-threadleaf sedge (Carex filifolia) and creeping

juniper (Juniperus horizontalis)/little bluestem habitat types [28,29].

In the Black Hills silver buffaloberry occurs in a bur oak (Quercus

macrocarpa)/skunkbush sumac (Rhus trilobata) association [34]. In North

Dakota silver buffaloberry is the dominant shrub in the little Missouri

River Badlands [39].

The following publication lists silver buffaloberry as a community

dominant:

The vegetation of the Grand River/Cedar River, Sioux, and Ashland

Districts of the Custer National Forest: a habitat type classification

[28]

Species not previously mentioned but commonly associated with silver

buffaloberry include plains cottonwood (Populus deltoides), American elm

(Ulmus americana), thinleaf alder (Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia),

boxelder (Acer negundo), American plum (Prunus americana), hackberry

(Celtis occidentalis), red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea), Wood's rose

(Rosa woodsii), Arkansas rose (R. arkansana), Saskatoon serviceberry

(Amelanchier alnifolia), basin big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp.

tridentata), fringed sage (A. frigida), shrubby cinquefoil (Potentilla

fruticosa), rubber rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus nauseous), black

greasewood (Sarcobatus vermiculatus), sideoats grama (Bouteloua

curtipendula), big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii var. gerardii),

Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratense), plains muhly (Muhlenbergia

cuspidata), field horsetail (Equisetum arvense), Canada wildrye (Elymus

canadensis), yellow sweetclover (Melilotus officinalis), white

sweetclover (M. alba), and starry Solomon-seal (Smilacina stellata)

[2,4,6,28,45,73].

MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

SPECIES: Shepherdia argentea

IMPORTANCE TO LIVESTOCK AND WILDLIFE :

Silver buffaloberry is a valuable forage species for mule deer,

pronghorn, and grizzly bear [11,54,75,86]. It is browsed by mule deer

in Montana and constituted 15 percent of mule deer summer diets in 1969

[11]. In North Dakota silver buffaloberry is an important browse

species in mule deer winter diets [39]. In the northern Great Basin,

deer and elk browse silver buffaloberry [54].

In Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota, silver buffaloberry fruits

are eaten by sharp-tailed grouse, cedar waxwings, other passerine

species, and small mammals [14,41,44,76]. In the northern Great Plains,

the fruit of silver buffaloberry provides the best native winter food

source for sharp-tailed grouse [15,44]. In Montana sharp-tailed grouse

feed primarily on silver buffaloberry buds in the winter [76].

Silver buffaloberry is nearly worthless as livestock forage due to its

thornlike twigs [39,41]. In Utah cattle and sheep make limited use of

silver buffaloberry [41]. In the northern Great Basin, silver

buffaloberry is fair forage for sheep [54]. Forage production under

dense, thorny, monotypic stands of silver buffaloberry is low; as stands

open up, forage production increases due to invasion by Kentucky

bluegrass [28].

PALATABILITY :

Palatability ratings for silver buffaloberry are as follows [10,85]:

CO MT ND UT WY

cattle poor poor poor poor poor

sheep poor fair fair fair fair

horses poor poor poor poor poor

NUTRITIONAL VALUE :

Silver buffaloberry nutritional values are rated as follows [10]:

UT CO WY MT ND

elk fair fair fair ---- ----

mule deer fair ---- good good good

white-tailed deer ---- ---- fair fair poor

pronghorn fair ---- poor poor fair

upland game birds good ---- fair fair good

waterfowl fair ---- poor ---- ----

small nongame birds good good fair fair good

small mammals good ---- fair fair ----

Energy rating is fair and protein content is poor [31]; however,

Erickson [13] stated that the protein content of silver buffaloberry is

sufficient to meet maintenance requirements of sheep and cattle during

the growing season. Silver buffaloberry fruit gross energy is

4.937 kcal/gram oven-dry matter and crude protein is 8.4 percent of

oven-dry matter [14].

COVER VALUE :

Silver buffaloberry cover values are rated as follows [10,28]:

UT CO WY MT ND

elk fair ---- poor good ----

mule deer fair fair good good good

white-tailed deer good fair good good good

pronghorn fair ---- poor ---- fair

upland game birds good ---- good good good

waterfowl fair ---- poor ---- ----

small nongame birds good ---- good good good

small mammals ---- ---- good fair ----

In the northern Great Plains, silver buffaloberry provides nesting cover

for sharp-tailed grouse and many species of passerine birds [15,17,26].

In Montana the distribution of sharp-tailed grouse increases in areas

containing high densities (10-15% canopy cover) of silver buffaloberry

[59].

In Montana silver buffaloberry provides thermal and hiding cover for

livestock, upland game birds, small mammals, and big game [28]. In

North Dakota silver buffaloberry provides bedding sites for mule deer

[39].

VALUE FOR REHABILITATION OF DISTURBED SITES :

Silver buffaloberry adapts well to disturbed or degraded sites in the

Intermountain region [36,58]. It is used for multiple-row windbreaks,

shelterbelts, erosion control, wildlife habitat enhancement, and land

reclamation [36,44,77,85]. Nursery-grown stock readily establishes on

disturbed sites and once established, silver buffaloberry is a good soil

stabilizer [29]. Silver buffaloberry is used for erosion control in

riparian areas in the Intermountain region [52].

In the northern Great Plains, silver buffaloberry is not recommended for

shelterbelt plantings because of high winds which may uproot plants

[21,22]. Silver buffaloberry is an actinorhizal pioneer species that is

widely planted for land reclamation in the northern Great Plains [44].

It is used for rehabilitating mine spoils in the northern Great Plains

and Utah [4,5,39,85]. Restoration of coal mine spoils increases when

trickle irrigation is used for 2 years. In North Dakota this technique

increased the survival rate of silver buffaloberry by 257 percent [5].

Dryland techniques for establishment of silver buffaloberry on bentonite

and low-salt coal spoils was moderately successful; survival rate of

silver buffaloberry at the start of the third year was 7 percent [4].

OTHER USES AND VALUES :

Plains Indians and pioneers preserved the fruit of silver buffaloberry

and made a sauce from the berries that was eaten with bison meat

[28,36,39,41,68]. Today the fruit is used to make pies, jams, and

jellies [41,39,68].

Silver buffaloberry is planted as an ornamental [36,70].

OTHER MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS :

In the Black Hills silver buffaloberry has strong browsing resistance,

aided by thorny branches and the ability to sprout from the root crown

[85]. In Nevada silver buffaloberry decreases with grazing [43]. In

the Badlands of North Dakota, three green ash draws exposed to different

grazing intensities were selected to determine the effects of browsing

on silver buffaloberry height. The mean height of silver buffaloberry

on the lightly browsed, moderately browsed, and heavily browsed sites

was 8.2 feet (2.49 m), 7.1 feet (2.17 m), and 7.3 feet (2.21 m),

respectively. Both shrub- and tree-height silver buffaloberry had

highest density and percent cover on moderately browsed sites [8].

Silver buffaloberry fixes nitrogen [77].

Silver buffaloberry is susceptible to leaf spot, white heart rot, and

insect parasites [21,44,61]. White heart rot can lead to brittle wood

and subsequent breakage of branches by wind and snow [21]. Rodents may

harvest planted seeds and girdle young plants [85].

Silver buffaloberry is difficult to transplant from its native habitat

[39]. For field transplanting, root cuttings will give best results

[52]. At the Woodward Field Station in Oklahoma, 9-year-old silver

buffaloberry transplants were 9 feet (2.7 m) tall and similar in spread

to plants growing in native ranges, but were less vigorous [40].

In silver buffaloberry stands trails are established by livestock and

deer which may open the stands to invasion by weedy species [28].

BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS

SPECIES: Shepherdia argentea

|

| A silver buffaloberry sprout emerging from a rhizome. U.S. Forest Service photo by Janet Fryer. |

GENERAL BOTANICAL CHARACTERISTICS :

Silver buffaloberry is a native, deciduous, thicket-forming small tree

or large shrub with spreading to ascending thorny aboverground branches

and belowground rhizomes [47,32,87,85]. It grows from 3.3 to 20 feet

(1-6 m) tall [25,33,41,54]. Leaves are 0.8 to 2.0 inches (2-5 cm) long

and 0.28 to 0.4 inch (7-10 mm) wide [25,71]. The drupelike, ovoid fruit

is 0.16 to 0.24 inch (4-6 mm) long [36,47] and is one seeded [71]. In

western North Dakota, rooting patterns of 323 silver buffaloberry shrubs

were examined. On 12-year-old silver buffaloberry shrubs that were 12

feet (3.6 m) tall, 97 percent of the total roots were found in the first

4 feet (1.2 m) of soil. The longest root was 22 feet (6.6 m) long. The

maximum depth of root penetration was 5.8 feet (1.74 m).

Silver buffaloberry has thin, exfoliating bark with shallow furrows and

flat-topped ridges [71].

A study on relatively undisturbed sites in North Dakota showed that

silver buffaloberry stems were 1 to 32 years old, with an average age of

7.62 years [39].

RAUNKIAER LIFE FORM :

Phanerophyte

REGENERATION PROCESSES :

Sexual: Seed production begins at 4 to 6 years of age, with good seed

crops generally produced every 3 to 4 years [77]. The small, hard seed

shows poor and erratic germination. The embryo is dormant; cold

stratification at 41 degrees Fahrenheit (5 deg C) for 60 to 90 days will

increase germination [66,68,77]. Seed can be stored under cold, dry

conditions in the laboratory for 11 to 15 years and retain viability

[66]. Silver buffaloberry seed with a moisture content of 13.1 percent

showed 97 percent germination after 3.5 years of storage at 41 degrees

Fahrenheit (5 deg C) [77]. Seed is disseminated primarily by animals

[77].

Vegetative: Silver buffaloberry sprouts originate from a complex

network of underground stems and rootstocks [28,39,85]. It also sprouts

from the root crown [29]. Shrubs are interconnected for distances of up

to 20 feet (6 m). In western North Dakota no seedlings were found in

323 silver buffaloberry shrubs examined [39].

SITE CHARACTERISTICS :

Silver buffaloberry occurs in riparian areas such as wet meadows,

floodplains, terraces, and along streams, rivers, lakes, springs, and

ponds [8,32,25,30,39].

Silver buffaloberry grows best on moist to semiwet soils with good

drainage [28,70], but will grow in semishaded areas and on dry, exposed

hillsides [28,35,71,85,87]. It grows best on loam and sandy loam soils,

but occurs on clay, clay loam, and gravelly substrates as well

[8,17,28,70]. Silver buffaloberry is tolerant of poorly drained soils

and some flooding, but is intolerant of prolonged flooding and

permanently high water tables [28].

Elevations for silver buffaloberry are as follows:

feet meters

Arizona 5,000 1,500 [42]

California 3,300-6,600 1,000-2,000 [36]

Colorado 3,800-7,500 1,140-2,250 [10]

Montana 3,500-7,000 1,050-2,100 [10]

New Mexico 3,000-7,000 900-2,100 [39]

Nevada 3,500-6,500 1,050-1,950 [70]

Utah 5,000-7,000 1,500-2,100 [10]

Wyoming 3,500-7,000 1,050-2,100 [10]

SUCCESSIONAL STATUS :

Silver buffaloberry occurs in seral and climax communities. It is

generally shade intolerant, but grows in some shaded areas such as

semiwooded draws [29,36,85]. In New Mexico silver buffaloberry is an

obligate riparian species [9]. In North Dakota silver buffaloberry is

a pioneer species that invades grasslands [39]; it also occurs on older

portions of streams [55]. Silver buffaloberry is a highly competitive

species except with taller woody plants such as green ash [28,85].

In the northern Great Plains, silver buffaloberry forms dense, nearly

impenetrable thickets, often exceeding 6.6 feet (2 m) [28]. Where

there is abundant moisture and deep fertile soil, silver buffaloberry

may reach tree height; where conditions are severe, silver buffaloberry

persists as a low or medium shrub [57].

In California silver buffaloberry trees have suffered much crown

dieback as a result of water diversion; many of the damaged shrubs are

now regenerating from sprouts and seeds [73].

SEASONAL DEVELOPMENT :

Silver buffaloberry flowering dates are as follows:

California Apr-May [89]

Colorado Apr-Aug [10]

Great Plains May-Jun [25]

Montana Apr-Jun [77]

Nevada Apr-May [70]

North Dakota Apr-May [10]

Utah Apr-May [10]

Wyoming May-July [10]

Saskatchewan late Apr [33]

Fruit ripening occurs from July to September in the Great Plains, July

to August in Nevada, June to August in Montana, and in early August in

Saskatchewan [25,70,71,77]. Seed dispersal occurs from June to December

in Montana [77].

FIRE ECOLOGY

SPECIES: Shepherdia argentea

FIRE ECOLOGY OR ADAPTATIONS :

Silver buffaloberry has fair tolerance to fire in the dormant state and

sprouts from rhizomes following fire [28,85]. In North Dakota the

green ash/chokecherry and boxelder/chokecherry habitat types, in which

silver buffaloberry is common, are adapted to fire. When main trunks of

most shrubs and trees in these habitat types are damaged by fire, the

plants sprout from the root crown [30].

POSTFIRE REGENERATION STRATEGY :

Tall shrub, adventitious-bud root crown

Small shrub, adventitious-bud root crown

FIRE EFFECTS

SPECIES: Shepherdia argentea

IMMEDIATE FIRE EFFECT ON PLANT :

Silver buffaloberry is probably killed by severe fires. In the northern

Great Plains, silver buffaloberry abundance was greatly reduced by "hot"

fires in early August [37].

DISCUSSION AND QUALIFICATION OF FIRE EFFECT :

NO-ENTRY

PLANT RESPONSE TO FIRE :

Silver buffaloberry sprouts from the root crown and rhizomes following

fire [24,28,85]. Varying responses to fire have been reported. In

northern mixed-grass prairies, silver buffaloberry percent cover decreased

after spring and summer fires [45].

A 5 acre (2 ha) fire occurred in a plains cottonwood forest in Dinosaur

Park, Alberta, in August 1989. In July 1990, average percent canopy

cover of silver buffaloberry on burned and unburned sites was 0.0 and

0.3, respectively [53].

In North Dakota an October 1976 fire burned mixed-prairie and wooded

draw plant communities. Average densities (stems/sq m) of silver

buffaloberry within wooded draw transects in the summers of 1977 and

1978 were as follows [88]:

1977 1978

lower draw-burned 0.5 1.2

upper draw-burned 1.5 1.9

unburned --- 0.6

DISCUSSION AND QUALIFICATION OF PLANT RESPONSE :

NO-ENTRY

FIRE MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS :

Uses of fire specifically for managing silver buffaloberry are not

described in the literature. In the northern Great Plains prescribed

fire may be useful for opening up shrub thickets or triggering sprout

reproduction of remnant shrubs in failing stands [65].

REFERENCES

SPECIES: Shepherdia argentea

REFERENCES :

1. Arohonka, Tuula; Rousi, Arne. 1980. Karyotypes and C-bands in Shepherdia

and Elaeagnus. Ann. Bot. Fennici. 17(2): 258-263. [19605]

2. Baker, William L. 1989. Classification of the riparian vegetation of the

montane and subalpine zones in western Colorado. Great Basin Naturalist.

49(2): 214-228. [7985]

3. Bernard, Stephen R.; Brown, Kenneth F. 1977. Distribution of mammals,

reptiles, and amphibians by BLM physiographic regions and A.W. Kuchler's

associations for the eleven western states. Tech. Note 301. Denver, CO:

U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. 169 p.

[434]

4. Bjugstad, Ardell J. 1977. Reestablishment of woody plants on mine spoils

and management of mine water impoundments: an overview of Forest Service

research on the n. High Plains. In: Wright, R. A., ed. The reclamation

of disturbed lands. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press:

3-12. [4238]

5. Bjugstad, Ardell J. 1986. Wooded draws of the northern high plains:

characteristics, value and restoration (North and South Dakota).

Restoration & Management Notes. 4(2): 74-75. [4226]

6. Boldt, Charles E.; Uresk, Daniel W.; Severson, Kieth E. 1979. Riparian

woodlands in jeopardy on Northern High Plains. In: Johnson, R. Roy;

McCormick, J. Frank, technical coordinators. Strategies for protection &

management of floodplain wetlands & other riparian ecosystems: Proc. of

the symposium; 1978 December 11-13; Callaway Gardens, GA. Gen. Tech.

Rep. WO-12. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest

Service: 184-189. [4359]

7. Bormann, Bernard T. 1988. A masterful scheme: Symbiotic nitrogen-fixing

plants of the Pacific Northwest. University of Washington Arboretum

Bulletin. 51(2): 10-14. [6796]

8. Butler, Jack Lee. 1983. Grazing and topographic influences on selected

green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) communities in the North Dakota

Badlands. Fargo, ND: North Dakota State University. 130 p. Thesis.

[184]

9. Dick-Peddie, William A.; Hubbard, John P. 1977. Classification of

riparian vegetation. In: Johnson, R. Roy; Jones, Dale A., technical

coordinators. Importance, preservation and management of riparian

habitat: a symposium: Proceedings; 1977 July 9; Tucson, AZ. Gen. Tech.

Rep. RM-43. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest

Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: 85-90.

Available from: NTIS, Springfield, VA 22151; PB-274 582. [5338]

10. Dittberner, Phillip L.; Olson, Michael R. 1983. The plant information

network (PIN) data base: Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, Utah, and

Wyoming. FWS/OBS-83/86. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior,

Fish and Wildlife Service. 786 p. [806]

11. Dusek, Gary L. 1975. Range relations of mule deer and cattle in prairie

habitat. Journal of Wildlife Management. 39(3): 605-616. [5938]

12. Dusek, Gary L.; Wood, Alan K.; Mackie, Richard J. 1988. Habitat use by

white-tailed deer in prairie-agricultural habitat in Montana. Prairie

Naturalist. 20(3): 135-142. [6801]

13. Erickson, D. O.; Barder, W. T.; Wanapat, S.; Williamson, R. L. 1981.

Nutritional composition of common shrubs in North Dakota. Proceedings,

North Dakota Academy of Science. 35: 4. [6454]

14. Evans, Keith E.; Dietz, Donald R. 1974. Nutritional energetics of

sharp-tailed grouse during winter. Journal of Wildlife Management.

38(4): 622-629. [14152]

15. Evans, Keith E.; Probasco, George E. 1977. Wildlife of the prairies and

plains. Gen. Tech. Rep. NC-29. St. Paul, MN: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station. 18

p. [14118]

16. Eyre, F. H., ed. 1980. Forest cover types of the United States and

Canada. Washington, DC: Society of American Foresters. 148 p. [905]

17. Faanes, Craig A. 1987. Breeding birds and vegetation structure in

western North Dakota wooded draws. Prairie Naturalist. 19(4): 209-220.

[9764]

18. Farnsworth, Raymond B. 1975. Nitrogen fixation in shrubs. In: Stutz,

Howard C., ed. Wildland shrubs: Proceedings--symposium and workshop;

1975 November 5-7; Provo, UT. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University:

32-71. [909]

19. Fessenden, R. J. 1979. Use of actinorhizal plants for land reclamation

and amenity planting in the U.S.A. and Canada. In: Gordon, J. C.;

Wheeler, C. T.; Perry, D. A., eds. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation in the

management of temperate forests: Proceedings of a workshop; 1979 April

2-5; Corvallis, OR. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University, Forest

Research Laboratory: 403-419. [4308]

20. Garrison, George A.; Bjugstad, Ardell J.; Duncan, Don A.; [and others].

1977. Vegetation and environmental features of forest and range

ecosystems. Agric. Handb. 475. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service. 68 p. [998]

21. George, Ernest J. 1953. Thirty-one-year results in growing shelterbelts

on the Northern Great Plains. Circular No. 924. Washington, DC: U.S.

Department of Agriculture. 57 p. [4567]

22. George, Ernest J. 1953. Tree and shrub species for the Northern Great

Plains. Circular No. 912. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture. 46 p. [4566]

23. Girard, Michele M.; Goetz, Harold; Bjugstad, Ardell J. 1989. Native

woodland habitat types of southwestern North Dakota. Res. Pap. RM-281.

Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky

Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 36 p. [6319]

24. Girard, Michele M.; Goetz, Harold; Bjugstad, Ardell J. 1987. Factors

influencing woodlands of southwestern North Dakota. Prairie Naturalist.

19(3): 189-198. [2763]

25. Great Plains Flora Association. 1986. Flora of the Great Plains.

Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. 1392 p. [1603]

26. Grosz, Kevin Lee. 1988. Sharp-tailed grouse nesting and brood rearing

habitat in grazed and nongrazed treatments in southcentral North Dakota.

Fargo, ND: North Dakota State University. 72 p. M.S. thesis. [5491]

27. Hansen, Paul L.; Chadde, Steve W.; Pfister, Robert D. 1988. Riparian

dominance types of Montana. Misc. Publ. No. 49. Missoula, MT: University

of Montana, School of Forestry, Montana Forest and Conservation

Experiment Station. 411 p. [5660]

28. Hansen, Paul L.; Hoffman, George R. 1988. The vegetation of the Grand

River/Cedar River, Sioux, and Ashland Districts of the Custer National

Forest: a habitat type classification. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-157. Fort

Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky

Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 68 p. [771]

29. Hansen, Paul L.; Hoffman, George R.; Bjugstad, Ardell J. 1984. The

vegetation of Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota: a habitat

type classification. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-113. Fort Collins, CO: U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and

Range Experiment Station. 35 p. [1077]

30. Hansen, Paul; Boggs, Keith; Pfister, Robert; Joy, John. 1990.

Classification and management of riparian and wetland sites in central

and eastern Montana. Missoula, MT: University of Montana, School of

Forestry, Montana Forest and Conservation Experiment Station, Montana

Riparian Association. 279 p. [12477]

31. Hansen, Paul; Pfister, Robert; Joy, John; [and others]. 1989.

Classification and management of riparian sites in southwestern Montana.

Missoula, MT: University of Montana, School of Forestry, Montana

Riparian Association. 292 p. Draft Version 2. [8900]

32. Harrington, H. D. 1964. Manual of the plants of Colorado. 2d ed.

Chicago: The Swallow Press Inc. 666 p. [6851]

33. Hayes, P. A.; Steeves, T. A.; Neal, B. R. 1989. An architectural

analysis of Shepherdia canadensis and Shepherdia argentea: patterns of

shoot development. Canadian Journal of Botany. 67: 1870-1877. [7981]

34. Hayward, Herman E. 1928. Studies of plants in the Black Hills of South

Dakota. Botanical Gazette. 85(4): 353-412. [1110]

35. Hensley, David L.; Carpenter, Philip L. 1986. Survival and coverage by

several N2-fixing trees and shrubs on lime-avended acid mine spoil. Tree

Planters' Notes. 29: 27-31. [2845]

36. Hickman, James C., ed. 1993. The Jepson manual: Higher plants of

California. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. 1400 p.

[21992]

37. Higgins, Kenneth F.; Kruse, Arnold D.; Piehl, James L. 1989. Effects of

fire in the Northern Great Plains. Ext. Circ. EC-761. Brookings, SD:

South Dakota State University, Cooperative Extension Service, South

Dakota Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit. 47 p. [14749]

38. Hitchcock, C. Leo; Cronquist, Arthur. 1973. Flora of the Pacific

Northwest. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. 730 p. [1168]

39. Hladek, Kenneth Lee. 1971. Growth character. & utiliz. of buffaloberry

(Shepherdia argentea Nutt.) in the Little Missouri River badlands of

southwestern North Dakota. Fargo, ND: North Dakota State University of

Agriculture & Applied Sci. 115 p. Dissertation. [12120]

40. Johnson, E. W. 1963. Ornamental shrubs for the Southern Great Plains.

Farmer's Bull. 2025. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture. 62

p. [12064]

41. Johnson, James R.; Nichols, James T. 1970. Plants of South Dakota

grasslands: A photographic study. Bull. 566. Brookings, SD: South Dakota

State University, Agricultural Experiment Station. 163 p. [18501]

42. Kearney, Thomas H.; Peebles, Robert H.; Howell, John Thomas; McClintock,

Elizabeth. 1960. Arizona flora. 2d ed. Berkeley, CA: University of

California Press. 1085 p. [6563]

43. Klebenow, Donald A.; Oakleaf, Robert J. 1984. Historical avifaunal

changes in the riparian zone of the Truckee River, Nevada. In: Warner,

Richard E.; Hendrix, Kathleen M., eds. California riparian systems:

Ecology, conservation, and productive management: Proceedings of a

conference; 1981 September 17-19; Davis, CA. Berkeley, CA: University of

California Press: 203-209. [5835]

44. Knudson, Michael J.; Haas, Russell J.; Tober, Dwight A.; [and others].

1990. Improvement of chokecherry, silver buffaloberry, and hawthorn for

conservation use in the Northern Great Plains. In: McArthur, E. Durant;

Romney, Evan M.; Smith, Stanley D.; Tueller, Paul T., compilers.

Proceedings--symposium on cheatgrass invasion, shrub die-off, and other

aspects of shrub biology and management; 1989 April 5-7; Las Vegas, NV.

Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-276. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station: 291-299. [12863]

45. Kruse, Arnold D.; Higgins, Kenneth F. 1990. Effects of prescribed fire

upon wildlife habitat in northern mixed-grass prairie. In: Alexander, M.

E.; Bisgrove, G. F., technical coordinators. The art and science of fire

management: Proceedings, 1st Interior West Fire Council annual meeting

and workshop; 1988 October 24-27; Kananaskis Village, AB. Inf. Rep.

NOR-X-309. Edmonton, AB: Forestry Canada, Northwest Region, Northern

Forestry Centre: 182-193. [14146]

46. Kuchler, A. W. 1964. Manual to accompany the map of potential vegetation

of the conterminous United States. Special Publication No. 36. New York:

American Geographical Society. 77 p. [1384]

47. Lackschewitz, Klaus. 1991. Vascular plants of west-central

Montana--identification guidebook. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-227. Ogden, UT:

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research

Station. 648 p. [13798]

48. Landis, Thomas D.; Simonich, Edward J. 1984. Producing native plants as

container seedlings. In: Murphy, Patrick M., compiler. The challenge of

producing native plants for the Intermountain area: proceedings:

Intermountain Nurseryman's Association 1983 conference; 1983 August

8-11; Las Vegas, NV. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-168. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department

of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range

Experiment Station: 16-25. [6849]

49. Looman, J. 1980. The vegetation of the Canadian prairie provinces. II.

The grasslands, Part 1. Phytocoenologia. 8(2): 153-190. [18400]

50. Major, J.; Rejmanek, M. 1992. Amelanchier alnifolia vegetation in

eastern Idaho, USA and its environmental relationships. Vegetatio. 98:

141-156. [19831]

51. McElligott, Vincent T.; Sundt, Charles N.; Fay, Pete K.; Harstead, Kris.

1988. Goats, their control and use as a biological agent against leafy

spurge. In: Vegetative rehabilitation and equipment workshop: 42nd

annual report: Proceedings; 1988 February 21-22; Corpus Christi, TX.

2200--Range: 8822 2807. [Missoula, MT]: U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Forest Service, Technology & Development Program; U.S. Department of the

Interior: 41-42. [15428]

52. Monsen, Stephen B. 1983. Plants for revegetation of riparian sites

within the Intermountain region. In: Monsen, Stephen B.; Shaw, Nancy,

compilers. Managing Intermountain rangelands--improvement of range and

wildlife habitats: Proceedings of symposia; 1981 September 15-17; Twin

Falls, ID; 1982 June 22-24; Elko, NV. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-157. Ogden,

UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest

and Range Experiment Station: 83-89. [9652]

53. Mowat, Catherine. 1990. Fire effects study for Quail Flats Fire,

Dinosaur Provincial Park. Calgary, AB: Alberta Recreation, Parks and

Wildlife Foundation, Dinosaur National Park. 37 p. [+]. On file with:

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research

Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT. [17454]

54. Mozingo, Hugh N. 1987. Shrubs of the Great Basin: A natural history.

Reno, NV: University of Nevada Press. 342 p. [1702]

55. Nelson, Jack Raymond. 1961. Composition and structure of the principal

woody vegetation types in the North Dakota Badlands. Fargo, ND: North

Dakota State University. 195 p. Thesis. [161]

56. Nilson, David J. 1989. Woodland reclamation within the Missouri Breaks

in west central North Dakota. In: Walker, D. G.; Powter, C. B.; Pole, M.

W., compilers. Reclamation, a global perspective: Proceedings of the

conference; 1989 August 27-31; Calgary, AB. Edmonton, AB: Alberta Land

Conservation and Reclamation Council: 345-355. [14347]

57. Plummer, A. Perry. 1977. Revegetation of disturbed Intermountain area

sites. In: Thames, J. C., ed. Reclamation and use of disturbed lands of

the Southwest. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press: 302-337. [171]

58. Plummer, A. Perry. 1970. Plants for revegetation of roadcuts and other

disturbed or eroded areas. Range Improvement Notes. [Ogden, UT: U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Region]; 15(1):

1-10. [1897]

59. Prose, Bart L. 1987. Habitat suitability index models: plains

sharp-tailed grouse. Biological Report 82(10.142). Washington, DC: U.S.

Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, National Ecology

Center. 31 p. [23499]

60. Raunkiaer, C. 1934. The life forms of plants and statistical plant

geography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 632 p. [2843]

61. Riffle, Jerry W.; Peterson, Glenn W., technical coordinators. 1986.

Diseases of trees in the Great Plains. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-129. Fort

Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky

Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 149 p. [16989]

62. Sanford, Richard Charles. 1970. Skunk bush (Rhus trilobata Nutt.) in the

North Dakota Badlands: ecology, phytosociology, browse production, and

utilization. Fargo, ND: North Dakota State University. 165 p.

Dissertation. [272]

63. Schroeder, W. R. 1988. Planting and establishment of shelterbelts in

humid severe-winter regions. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment.

22/23: 441-463. [8774]

64. Severson, Kieth E.; Boldt, Charles E. 1978. Cattle, wildlife, and

riparian habitats in the western Dakotas. In: Management and use of

northern plains rangeland: Reg. rangeland symposium; 1978 February

27-28; Bismarck, ND. Dickinson, ND: North Dakota State University:

90-103. [65]

65. Severson, Kieth E.; Boldt, Charles E. 1977. Problems associated with

management of native woody plants in the western Dakotas. In: Johnson,

Kendall L., editor. Wyoming shrublands: Proceedings, 6th Wyoming shrub

ecology workshop; 1977 May 24-25; Buffalo, WY. Laramie, WY: Shrub

Ecology Workshop: 51-57. [2759]

66. Shaw, N. 1984. Producing bareroot seedlings of native shrubs. In:

Murphy, P. M., compiler. The challenge of producing native plants for

the Intermountain area: Proceedings, Intermountain Nurseryman's

Association conference; 1983 August 8-11; Las Vegas, NV. Gen. Tech. Rep.

INT-168. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service,

Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: 6-15. [6850]

67. Shiflet, Thomas N., ed. 1994. Rangeland cover types of the United

States. Denver, CO: Society for Range Management. 152 p. [23362]

68. Smith, Ronald C. 1987. Shepherdia argentea. American Nurseryman.

166(10): 134. [24414]

69. St. Pierre, Richard G.; Steeves, Taylor A. 1990. Observations on shoot

morphology, anthesis, flower number, and seed production in the

saskatoon, Amelanchier alnifolia (Rosaceae). Canadian Field-Naturalist.

104(3): 379-386. [14119]

70. Stark, N. 1966. Review of highway planting information appropriate to

Nevada. Bull. No. B-7. Reno, NV: University of Nevada, College of

Agriculture, Desert Research Institute. 209 p. In cooperation with:

Nevada State Highway Department. [47]

71. Stephens, H. A. 1973. Woody plants of the North Central Plains.

Lawrence, KS: The University Press of Kansas. 530 p. [3804]

72. Stickney, Peter F. 1989. Seral origin of species originating in northern

Rocky Mountain forests. Unpublished draft on file at: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire

Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT; RWU 4403 files. 7 p. [20090]

73. Stromberg, Julie C.; Patten, Duncan T. 1989. Early recovery of an

eastern Sierra Nevada riparian system after 40 years of stream

diversion. In: Abell, Dana L., technical coordinator. Proceedings of the

California riparian systems conference: Protection, management, and

restoration for the 1990's; 1988 September 22-24; Davis, CA. Gen. Tech.

Rep. PSW-110. Berkeley, CA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest

Service, Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Experiment Station: 399-404.

[13770]

74. Stromberg, Juliet C.; Patten, Duncan T. 1992. Mortality and age of black

cottonwood stands along diverted and undiverted streams in the eastern

Sierra Nevada, California. Madrono. 39(3): 205-223. [19148]

75. Sundstrom, Charles; Hepworth, William G.; Diem, Kenneth L. 1973.

Abundance, distribution and food habits of the pronghorn: A partial

characterization of the optimum pronghorn habitat. Bulletin No. 12.

Boise, ID: U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, Division of

River Basin Studies. 59 p. [5906]

76. Swenson, Jon E. 1985. Seasonal habitat use by sharp-tailed grouse,

Tympanuchus phasianellus, on mixed-grass prairie in Montana. Canadian

Field-Naturalist. 99(1): 40-46. [23501]

77. Thilenius, John F.; Evans, Keith E.; Garrett, E. Chester. 1974.

Shepherdia Nutt. buffaloberry. In: Schopmeyer, C. S., ed. Seeds of

woody plants in the United States. Agric. Handb. 450. Washington, DC:

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: 771-773. [7753]

78. Tinus, Richard W. 1984. Salt tolerance of 10 deciduous shrub and tree

species. In: Murphy, Patrick M., compiler. The challenge of producing

native plants for the Intermountain area: Proceedings: Intermountain

Nurseryman's Association 1983 conference; 1983 August 8-11; Las Vegas,

NV. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-168. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station:

44-49. [6848]

79. Tolstead, W. L. 1941. Plant communities and secondary succession in

south-central South Dakota. Ecology. 22(3): 322-328. [5887]

80. Tuskan, Gerald A.; Laughlin, Kevin. 1991. Windbreak species performance

and management practices as reported by Montana and North Dakota

landowners. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation. 46(3): 225-228.

[15084]

81. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service. 1994. Plants

of the U.S.--alphabetical listing. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service. 954 p. [23104]

82. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Biological Survey. [n.d.]. NP

Flora [Data base]. Davis, CA: U.S. Department of the Interior, National

Biological Survey. [23119]

83. Uresk, Daniel W.; Boldt, Charles E. 1986. Effect of cultural treatments

on regeneration of native woodlands on the Northern Great Plains.

Prairie Naturalist. 18(4): 193-201. [3836]

84. Vines, Robert A. 1960. Trees, shrubs, and woody vines of the Southwest.

Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. 1104 p. [7707]

85. Wasser, Clinton H. 1982. Ecology and culture of selected species useful

in revegetating disturbed lands in the West. FWS/OBS-82/56. Washington,

DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. 347 p.

[15400]

86. Weaver, John L. 1985. Charting the course: The Forest Service grizzly

bear conservation program. Missoula, MT: U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Forest Service, Region 1. 11 p. Report on file with: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire

Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT. [17282]

87. Welsh, Stanley L.; Atwood, N. Duane; Goodrich, Sherel; Higgins, Larry

C., eds. 1987. A Utah flora. Great Basin Naturalist Memoir No. 9. Provo,

UT: Brigham Young University. 894 p. [2944]

88. Zimmerman, Gregory M. 1981. Effects of fire upon selected plant

communities in the Little Missouri Badlands. Fargo, ND: North Dakota

State University. 60 p. Thesis. [5121]

89. Thompson, Robert S.; Anderson, Katherine H.; Bartlein, Patrick J. 1999.

Digital representations of tree species range maps from "Atlas of United

States trees" by Elbert L. Little, Jr. (and other publications). In: Atlas

of relations between climatic parameters and distributions of important

trees and shrubs in North America. Denver, CO: U.S. Geological Survey,

Information Services (Producer). On file at: U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory,

Missoula, MT; FEIS files. [92575]

FEIS Home Page