Index of Species Information

SPECIES: Thamnosma montana

|

|

|

| Turpentinebroom at Desert Hot Springs, CA. Image by J. E.(Jed) and Bonnie McClellan © California Academy of Sciences. Used with permission. |

Introductory

SPECIES: Thamnosma montana

AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION:

Tesky, Julie L. 1994. Thamnosma montana.In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station,

Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available:

https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/shrub/thamon/all.html [].

Revisions:

On 27 August 2018, the common name of this species was changed in FEIS

from: Mojave desertrue

to: turpentinebroom. Images were also added.

ABBREVIATION:

THAMON

SYNONYMS:

NO-ENTRY

NRCS PLANT CODE:

THMO

COMMON NAMES:

turpentinebroom

cordoncillo

Mojave desertrue

TAXONOMY:

The scientific name of turpentinebroom is Thamnosma

montana Torrey & Fren. (Rutaceae) [3,15,18,22,30]. There are no recognized

infrataxa.

LIFE FORM:

Shrub

FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS:

No special status

OTHER STATUS:

NO-ENTRY

DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE

SPECIES: Thamnosma montana

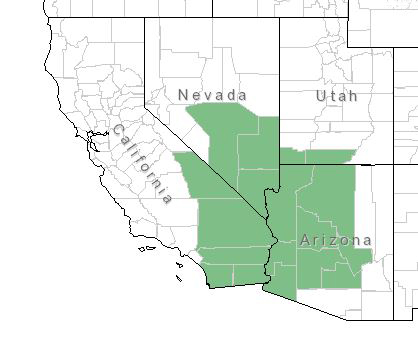

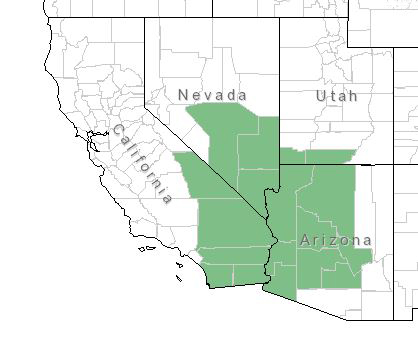

GENERAL DISTRIBUTION:

Turpentinebroom is found in the Mojave, Sonora, and Colorado deserts of

Baja California, southern California, southern Nevada (Nye and Clark

counties), southwestern Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and Mexico

[3,13,15,18,22].

|

| Distribution of turpentinebroom in the United States. Map courtesy of USDA, NRCS. 2018. The PLANTS Database.

National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC. [2018, August 27] [25]. |

ECOSYSTEMS:

FRES29 Sagebrush

FRES30 Desert shrub

FRES35 Pinyon - juniper

STATES:

AZ CA NM NV UT MEXICO

BLM PHYSIOGRAPHIC REGIONS:

3 Southern Pacific Border

7 Lower Basin and Range

12 Colorado Plateau

13 Rocky Mountain Piedmont

KUCHLER PLANT ASSOCIATIONS:

K023 Juniper - pinyon woodland

K024 Juniper steppe woodland

K039 Blackbrush

K040 Saltbush - greasewood

K041 Creosotebush

K042 Creosotebush - bursage

K044 Creosotebush - tarbush

SAF COVER TYPES:

238 Western juniper

239 Pinyon - juniper

SRM (RANGELAND) COVER TYPES:

NO-ENTRY

HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES:

Turpentinebroom is commonly found in creosotebush (Larrea tridentata)

scrub, blackbrush (Coleogyne ramosissima) scrub, and other warm desert

shrub communities, and in Joshua tree (Yucca brevifolia) and

pinyon-juniper (Pinus spp.-Juniperus spp.) woodlands [5,6,27,18,30]. In

addition to the above mentioned species, turpentinebroom is commonly

associated with desertsenna (Cassia armata), Nevada ephedra (Ephedra

nevadensis), banana yucca (Yucca baccata), Mojave yucca (Y. schidigera),

spiny hopsage (Grayia spinosa), winterfat (Ceratoides lanata), budsage

(Artemisia spinescens), Utah agave (Agave utahensis), purple sage

(Salvia dorrii), desert almond (Prunus fasciculatus), Dalea spp.,

Atriplex spp., Tetradymia spp., Eriogonum spp., and Lycium spp.

[8,23,27]. Turpentinebroom is not listed as a dominant or indicator

species in the available literature.

MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

SPECIES: Thamnosma montana

IMPORTANCE TO LIVESTOCK AND WILDLIFE:

Turpentinebroom is occasionally browsed by desert bighorn sheep [5].

PALATABILITY:

Turpentinebroom is not palatable to livestock [26].

NUTRITIONAL VALUE:

NO-ENTRY

COVER VALUE:

NO-ENTRY

VALUE FOR REHABILITATION OF DISTURBED SITES:

NO-ENTRY

OTHER USES AND VALUES:

Turpentinebroom has been used by the Indians as a tonic and in the

treatment of gonorrhea [15].

OTHER MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

Turpentinebroom commonly accumulates organic material and windblown

soil beneath its crown. These shrub mounds serve as an increased source

of nutrients and water for turpentinebroom in addition to providing a

microhabitat for desert ephemerals [6].

BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS

SPECIES: Thamnosma montana

GENERAL BOTANICAL CHARACTERISTICS:

Turpentinebroom is a native, long-lived, profusely branched, deciduous,

perennial shrub 1 to 2.5 feet (30-80 cm) tall [3,22]. It has stout,

spine-tipped, broomlike branches that are thickly covered with

blisterlike glands and are leafless most of the year [6,13].

Turpentinebroom forms new branches from the root crown, resulting in multiple

stems arising from the ground [6,9]. The leaves are 0.16 to 0.6 inch

(4-15 mm) long and 0.04 inch (1 mm) wide [3,22]. The flowers are in

small cymose or racemose clusters [15].

|

| Turpentinebroom fruits. Image by Charles Webber, © California Academy of Sciences. Used with permission. |

RAUNKIAER LIFE FORM:

Phanerophyte

REGENERATION PROCESSES:

Turpentinebroom reproduces by seed. The flowers are animal pollinated

and the fruit is dispersed by animals [19]. The fruit is a capsule

containing one to three seeds [22,30]. The ability of turpentinebroom

to reproduce vegetatively was not specifically described in the

literature. However, since it branches from the root crown,

turpentinebroom may be able to sprout after top-kill.

SITE CHARACTERISTICS:

Turpentinebroom is commonly found on sunny, dry, rocky, or gravelly

slopes and mesas. [3,22,26]. It occurs at the following elevations:

Arizona - 4,500 feet (1,371 m) and lower [15]

California - 5,500 feet (1,676) and lower [18]

Utah - 2,316 to 4,265 feet (760-1,300 m) [30].

SUCCESSIONAL STATUS:

Turpentinebroom is present in most stages of succession. Wells [32]

described it as a pioneer shrub typically found in disturbed areas such

as drainageways and actively eroded bedrock areas. Others have reported

that turpentinebroom is a long-lived shrub, present in later stages of

desert succession [27,28]. On a sandy bajada in California,

turpentinebroom was one of the most common species found in an old, stable

creosotebush scrub community [27].

SEASONAL DEVELOPMENT:

Turpentinebroom flowers in the spring at the same time new vegetative

shoots are being initiated [9,15,18]. It flowers from February through

April in Arizona, and from March through May in California [15,18].

Turpentinebroom leaves are deciduous and are shed soon after flowering

[3], but the twigs often remain green for 3 to 5 years [9,22].

FIRE ECOLOGY

SPECIES: Thamnosma montana

FIRE ECOLOGY OR ADAPTATIONS:

Regeneration of turpentinebroom after fire in not described in research

currently available. However, since it produces new branches from the

root crown, it probably can sprout from the root crown if top-killed by

fire. Turpentinebroom probably also colonizes burned areas via

animal-dispersed seeds.

Fire frequency in the communities where turpentinebroom occurs depends

on productivity and continuity of fuels. Where livestock grazing has

reduced grass cover and accelerated erosion, fire frequency has

decreased [17,31]. In creosotebush scrub communities, fires generally

occur in those occasional years when exceptionally heavy winter rains

have produced abnormally heavy stands of annuals [14]. Fires are also

rare in blackbrush communities; however, these communities have been

known to burn under conditions of high temperature, high wind velocity,

and low relative humidity [14]. Pinyon-juniper communities historically

burned every 10 to 30 years [31].

POSTFIRE REGENERATION STRATEGY:

Small shrub, adventitious-bud root crown

Initial-offsite colonizer (off-site, initial community)

Secondary colonizer - off-site seed

FIRE REGIMES: Find fire regime information for the plant communities in

which this species may occur by entering the species name in the

FEIS home page under "Find Fire Regimes".

FIRE EFFECTS

SPECIES: Thamnosma montana

IMMEDIATE FIRE EFFECT ON PLANT:

Information was not available regarding the immediate effects of fire on

turpentinebroom. Turpentinebroom is probably top-killed or killed by

most fires.

DISCUSSION AND QUALIFICATION OF FIRE EFFECT:

NO-ENTRY

PLANT RESPONSE TO FIRE:

Turpentinebroom was present on a burn in the Sonoran Desert, Arizona,

within 4 years of a June fire [33]. The absolute cover value of

turpentinebroom following controlled fires in a blackbrush community in

southwestern Utah is as follows [7]:

Absolute cover value (percent)

Time elapsed since burning mean standard deviation

unburned 0.9 2.3

1 year 0.5 0.8

2 years 0 0

6 years 0 0

12 years 0 0

17 years 0 0

19.5 years 11.7 3.8

37 years 15.4 11.4

The 37-year-old site was dominated by shrubs and annual grasses.

Turpentinebroom had the greatest absolute cover value of any other species on

this site [7].

FIRE MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

For several decades after burning blackbrush communities, these sites

may be dominated by nonpalatable shrubs such as turpentinebroom.

Therefore, prescribed burning is not recommended in blackbrush

communities to improve forage for livestock [33].

REFERENCES

SPECIES: Thamnosma montana

REFERENCES:

1. Anderson, D. J.; Perry, R. A.; Leigh, J. H. 1972. Some perspectives on

shrub/environment interactions. In: McKell, Cyrus M.; Blaisdell, James;

Goodin, Joe R., tech. eds. Wildland shrubs--their biology and

utilization: An international symposium: Proceedings; 1971 July; Logan,

UT. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station:

172-181. [3794]

2. Bates, Patricia A. 1983. Prescribed burning blackbrush for deer habitat

improvement. Cal-Neva Wildlife Transactions. [Volume unknown]: 174-182.

[4458]

3. Benson, Lyman; Darrow, Robert A. 1981. The trees and shrubs of the

Southwestern deserts. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press.

[18066]

4. Bernard, Stephen R.; Brown, Kenneth F. 1977. Distribution of mammals,

reptiles, and amphibians by BLM physiographic regions and A.W. Kuchler's

associations for the eleven western states. Tech. Note 301. Denver, CO:

U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. 169 p.

[434]

5. Bradley, W. G. 1965. A study of the blackbrush plant community of the

Desert Game Range. Transactions, Desert Bighorn Council. 11: 56-61.

[4380]

6. Burk, Jack H. 1977. Sonoran Desert. In: Barbour, M. G.; Major, J., eds.

Terrestrial vegetation of California. New York: John Wiley and Sons:

869-899. [3731]

7. Callison, Jim; Brotherson, Jack D.; Bowns, James E. 1985. The effects of

fire on the blackbrush [Coleogyne ramosissima] community of southwestern

Utah. Journal of Range Management. 38(6): 535-538. [593]

8. Cody, M. L. 1986. Spacing patterns in Mojave Desert plant communities:

near-neighbor analyses. Journal of Arid Environments. 11: 199-217.

[4411]

9. Comstock, J. P.; Cooper, T. A.; Ehleringer, J. R. 1988. Seasonal

patterns of canopy development and carbon gain in nineteen warm desert

shrub species. Oecologia. 75(3): 327-335. [22222]

10. Dittberner, Phillip L.; Olson, Michael R. 1983. The plant information

network (PIN) data base: Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, Utah, and

Wyoming. FWS/OBS-83/86. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior,

Fish and Wildlife Service. 786 p. [806]

11. Eyre, F. H., ed. 1980. Forest cover types of the United States and

Canada. Washington, DC: Society of American Foresters. 148 p. [905]

12. Garrison, George A.; Bjugstad, Ardell J.; Duncan, Don A.; [and others].

1977. Vegetation and environmental features of forest and range

ecosystems. Agric. Handb. 475. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service. 68 p. [998]

13. Hickman, James C., ed. 1993. The Jepson manual: Higher plants of

California. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. 1400 p.

[21992]

14. Humphrey, Robert R. 1974. Fire in the deserts and desert grassland of

North America. In: Kozlowski, T. T.; Ahlgren, C. E., eds. Fire and

ecosystems. New York: Academic Press: 365-400. [14064]

15. Kearney, Thomas H.; Peebles, Robert H.; Howell, John Thomas; McClintock,

Elizabeth. 1960. Arizona flora. 2d ed. Berkeley, CA: University of

California Press. 1085 p. [6563]

16. Kuchler, A. W. 1964. Manual to accompany the map of potential vegetation

of the conterminous United States. Special Publication No. 36. New York:

American Geographical Society. 77 p. [1384]

17. Leopold, Aldo. 1924. Grass, brush, timber, and fire in southern Arizona.

Journal of Forestry. 22(6): 1-10. [5056]

18. Munz, Philip A. 1974. A flora of southern California. Berkeley, CA:

University of California Press. 1086 p. [4924]

19. Pendleton, Rosemary L.; Pendleton, Burton K.; Harper, Kimball T. 1989.

Breeding systems of woody plant species in Utah. In: Wallace, Arthur;

McArthur, E. Durant; Haferkamp, Marshall R., compilers.

Proceedings--symposium on shrub ecophysiology and biotechnology; 1987

June 30 - July 2; Logan, UT. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-256. Ogden, UT: U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research

Station: 5-22. [5918]

20. Raunkiaer, C. 1934. The life forms of plants and statistical plant

geography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 632 p. [2843]

21. Rowlands, Peter G. 1980. Recovery, succession, and revegetation in the

Mojave Desert. In: Rowlands, Peter G., ed. The effects of disturbance on

desert soils, vegetation & community processes with emphasis on off road

vehicles: a critical review. Special Publication, Desert Plan Staff.

Riverside, CA: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land

Management: 75-119. [20680]

22. Shreve, F.; Wiggins, I. L. 1964. Vegetation and flora of the Sonoran

Desert. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. 2 vols. [21016]

23. Smith, Stanley D.; Bradney, David J. M. 1990. Mojave Desert field trip.

In: McArthur, E. Durant; Romney, Evan M.; Smith, Stanley D.; Tueller,

Paul T., compilers. Proceedings--symposium on cheatgrass invasion, shrub

die-off, and other aspects of shrub biology and management; 1989 April

5-7; Las Vegas, NV. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-276. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department

of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station: 350-351.

[12871]

24. Stickney, Peter F. 1989. Seral origin of species originating in northern

Rocky Mountain forests. Unpublished draft on file at: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire

Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT; RWU 4403 files. 7 p. [20090]

25. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2018.

PLANTS Database, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources

Conservation Service (Producer). Available: https://plants.usda.gov/. [34262]

26. Van Dersal, William R. 1938. Native woody plants of the United States,

their erosion-control and wildlife values. Washington, DC: U.S.

Department of Agriculture. 362 p. [4240]

27. Vasek, Frank C.; Barbour, Michael G. 1977. Mojave desert scrub

vegetation. In: Barbour, M. G.; Major, J., eds. Terrestrial vegetation of

California. New York: John Wiley and Sons: 835-867. [3730]

28. Vasek, F. C.; Johnson, H. B.; Eslinger, D. H. 1975. Effects of pipeline

construction on creosote bush scrub vegetation of the Mojave Desert.

Madrono. 23(1): 1-13. [3429]

29. Vasek, Frank C.; Thorne, Robert F. 1977. Transmontane coniferous

vegetation. In: Barbour, Michael G.; Major, Jack, eds. Terrestrial

vegetation of California. New York: John Wiley & Sons: 797-832. [4265]

30. Welsh, Stanley L.; Atwood, N. Duane; Goodrich, Sherel; Higgins, Larry

C., eds. 1987. A Utah flora. Great Basin Naturalist Memoir No. 9. Provo,

UT: Brigham Young University. 894 p. [2944]

31. Wright, Henry A.; Bailey, Arthur W. 1982. Fire ecology: United States

and southern Canada. New York: John Wiley & Sons. 501 p. [2620]

32. Wells, Philip V. 1961. Succession in desert vegetation on streets of a

Nevada ghost town. Science. 134: 670-671. [4959]

33. Rogers, Garry F.; Steele, Jeff. 1980. Sonoran Desert fire ecology. In:

Stokes, Marvin A.; Dieterich, John H., technical coordinators.

Proceedings of the fire history workshop; 1980 October 20-24; Tucson,

AZ. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-81. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment

Station: 15-19. [16036]

FEIS Home Page