Index of Species Information

SPECIES: Casuarina spp.

|

|

|

| River sheoak fruits. Wikimedia Commons image by Rickpelleg. |

|

|

| Beach sheoak male and female flowers. Wikimedia Commons image by B. Navez. |

Gray sheoak fruits. Wikimedia Commons image by Margaret Donald. |

Introductory

SPECIES: Casuarina spp.

AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION:

Snyder, S. A. 1992. Casuarina spp. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station,

Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available:

https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/tree/casspp/all.html [].

Revisions:

On 2 March 2018, the common name of Casuarina equisetifolia was changed in FEIS

from: Australian-pine

to: beach sheoak. Images were also added.

ABBREVIATION:

CASSPP

CASCUN

CASEQU

CASGLA

SYNONYMS:

For Casuarina cunninghamiana:

Casuarina litoria L.

NRCS PLANT CODE [16]:

CASUA

CACU8

CAEQ

CAGL11

COMMON NAMES:

For Cunningham casuarina:

river sheoak

river-oak

sheoak

she-oak

For Casuarina equisetifolia:

beach sheoak

Australian-pine

horestail casuarina

For Casuarina glauca:

grey sheoak

ironwood

longleaf casuarina

whistling pine

TAXONOMY:

The scientific name of the sheoak genus is Casuarina (Casuarinaceae) [12,19].

Three species of sheoak are common in the United States. All will be treated

in this report because of their similar status as invader species and

across-the-board efforts to eradicate the genus from the continent.

"Sheoak" refers to the genus. The species covered in this review are:

Casuarina cunninghamiana Miq., river sheoak

Casuarina equisetifolia L., beach sheoak

Casuarina glauca Seiber, gray sheoak [6,19]

These species hybridize with each other [14].

LIFE FORM:

Tree

FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS:

NO_ENTRY

OTHER STATUS:

All 3 species of sheoak are list as noxious weeds (prohibited aquatic

plants, Class 1) in Florida [16].

DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE

SPECIES: Casuarina spp.

GENERAL DISTRIBUTION:

Sheoaks were introduced to the United States near the turn of the

20th century [14]. They are widely distributed in southern Florida

and are also found in California, Arizona, and Hawaii [12,17].

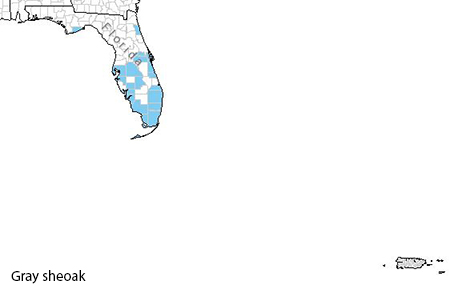

| Distributions of river, beach, and gray sheoak. Maps courtesy of USDA, NRCS. 2018. The PLANTS Database.

National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC [2018, June 8] [16]. |

|

|

ECOSYSTEMS:

FRES12 Longleaf - slash pine

FRES13 Loblolly - shortleaf pine

FRES16 Oak - gum - cypress

FRES41 Wet grasslands

STATES:

AZ CA FL HI MEXICO

BLM PHYSIOGRAPHIC REGIONS:

3 Southern Pacific Border

7 Lower Basin and Range

KUCHLER PLANT ASSOCIATIONS:

K080 Marl - Everglades

K091 Cypress savanna

K092 Everglades

SAF COVER TYPES:

70 Longleaf pine

75 Shortleaf pine

80 Loblolly pine - shortleaf pine

81 Loblolly pine

83 Longleaf pine - slash pine

84 Slash pine

111 South Florida slash pine

SRM (RANGELAND) COVER TYPES:

None

HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES:

River sheoak is listed as a component in the following vegetation

types:

Area Classification Authority

Mariana Is, S. Pacific veg. type Falanruw & others 1989 [5]

Palau, S. Pacific veg. type Cole & others 1987 [2]

MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

SPECIES: Casuarina spp.

WOOD PRODUCTS VALUE:

Sheoak wood has many uses, including fuelwood, poles, posts,

beams, oxcart tongues, shingles, paneling, fence rails, furniture,

marine pilings, tool handles, and cabinets [3,12]. The wood, however,

is subject to cracking and splitting [14].

IMPORTANCE TO LIVESTOCK AND WILDLIFE:

Sheoak poses a serious threat to some wildlife species. Nest

sites of three endangered species, the American crocodile (Crocodylus

acutus), the loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta ssp. caretta), and the

gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus), are all threatened by Australian

pine invasion [9,10]. Also, this invader creates sterile foraging and

breeding environments for small mammals [3,14]. It does, however,

provide food for migrating goldfinches which feed on sheoak

seeds [3].

PALATABILITY:

NO-ENTRY

NUTRITIONAL VALUE:

Tannins in the leaves of sheoak are carcinogenic and could be

fatal to foraging cattle, which sometimes eat the leaves [3].

COVER VALUE:

NO-ENTRY

VALUE FOR REHABILITATION OF DISTURBED SITES:

Sheoak was once used in the United States for reclaiming eroded

areas, but many land managers condemn its use because it threatens

indigenous plants and animals [12]. Some African and Asian countries

use it to combat desertification [17].

OTHER USES AND VALUES:

Sheoak has various medicinal uses and is also used for dyes, as

an ornamental, and in windbreaks [12]. C. cunninghamiana (the most

cold-hardy) can be planted in citrus groves to protect fruit trees from

cold [14].

OTHER MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

Sheoak is extremely fast growing, crowding out many native

plants and creating sterile environments for both plants and animals

[10]. It forms dense roots, which deplete soil moisture and break water

and sewer lines. It is also susceptible to windthrow during hurricanes

[3]. Cutting often induces sprouting, so it is not an effective control

method. Chemicals, such as 2,4,5-T, 2,4-D, or Garlon 3A, can be used to

eradicate sheoak [10,14].

BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS

SPECIES: Casuarina spp.

GENERAL BOTANICAL CHARACTERISTICS:

Sheoaks are medium to tall evergreen trees. They have stout

trunks with rough bark and erect or semispreading main branches and

drooping twigs [12]. Leaves are jointed and scalelike. The fruits

are round and warty with winged seeds. Trees can be dioecious or

monoecious; male flowers are borne at the tips of twigs, while female

flowers form on nonshedding branches [3,14]. Sheoak fixes

nitrogen with the aid of Frankia spp. fungi.

Characteristics of individual species are as follows:

C. cunninghamiana - 80 feet (25 m) in height, 2 feet (6 m) d.b.h.,

dioecious, nonsprouter.

C. equisetifolia - 50 to 100 feet (15-30 m) in height, 1.0 to 1.5 feet

(3-5 m) d.b.h., monoecious, nonsprouter.

C. glauca - 40 to 50 feet (10-15 m) in height, 1.5 feet (5 m) d.b.h.,

dioecious, agressive sprouter, in Florida, usually does not

produce fruit [12].

RAUNKIAER LIFE FORM:

Phanerophyte

REGENERATION PROCESSES:

Sheoaks regenerate by seed as well as vegetatively through

sprouting [3,12,14]. They are fast growing (5 to 10 feet [1.5-3 m] per

year) [14]. Seeds average 300,000 per pound. No pregermination

treatment is necessary. Seeds can remain fertile for a few months to a

year and will germinate in moist and porous soil, sometimes within 4 to

8 days of dispersal [14].

SITE CHARACTERISTICS:

Because of its nitrogen-fixing capability, sheoak can colonize

nutrient-poor soils [12]. It can grow in sloughs, sawgrass (Cladium

jamaicensis) glades, wet prairies, saltmarshes, pinelands, along rocky

coasts, on sandbars, dunes, and islands, and in water-logged clay or

brackish tidal areas [3,10,14,17,18]. C. equisetifolia is found only in

south Florida because of its cold intolerance. It is resistant to salt

spray but not to prolonged flooding. C. cunninghaminana grows along

freshwater streambanks and is not salt tolerant [3]. It is more

resistant to cold temperatures than C. equisetifolia [12]. C. glauca

grows on steep slopes as well as in intermittently flooded or poorly

drained sites. It is salt tolerant [3].

Some associates of sheoak include eucalyptus (Eucalyptus spp.),

melaleuca (Melaleuca quinquenervia), lovegrass (Eragrostis spp.), muhly

grasses (Huhlenbergia spp.), beard grasses (Andropogon spp.), plume

grass (Erianthus giganteus), saltbush (Baccharis halimifolia), wax

myrtle (Myrica cerifera), willow (Salix spp.), sweetbay (Magnolia

virginiana), redbay (Persia borbonia), and coco plum (Chrysobalanus

icaco) [18]. Native associates in the Northern Mariana Islands include

Neisosperma, Barringtonia, Terminalia, Heritiera, Cynometia, and Cordia

[5,6].

SUCCESSIONAL STATUS:

Sheoak is listed as a dominant species in some South Pacific

island's vegetation types [2,5,6]. It is a warm weather species, not

native to North America. It can be a primary or secondary colonizer in

disturbed areas of Florida [3,10].

SEASONAL DEVELOPMENT:

Sheoak can flower and fruit year-round in warm climates [3].

Its peak flowering time is between April and June, and its peak fruiting

time is between September and December. The minimum seed-bearing age is

4 to 5 years, and it produces a good seed crop annually. C.

equisetifolia usually flowers and fruits two times a year: between

February and April, and September and October. It produces fruit in

June and December. The fastest growth occurs in the first 7 years with

maximum growth reached in 20 years. The maximum lifespan of Australian

pine is 40 to 50 years [3].

FIRE ECOLOGY

SPECIES: Casuarina spp.

FIRE ECOLOGY OR ADAPTATIONS:

Sheoak less than 3 inches (8 cm) in diameter can sucker

following fire [3].

FIRE REGIMES :

Find fire regime information for the plant communities in which these

species may occur by entering the species' names in the FEIS home page under

"Find Fire Regimes".

POSTFIRE REGENERATION STRATEGY:

survivor species; on-site surviving root crown or caudex

off-site colonizer;seed carried by wind; postfire years 1 and 2

off-site colonizer; seed carried by animals or water; postfire yr 1&2

secondary colonizer; off-site seed carried to site after year 2

FIRE EFFECTS

SPECIES: Casuarina spp.

IMMEDIATE FIRE EFFECT ON PLANT:

Sheoaks greater than 3 inches (8 cm) in diameter are killed by fire [3].

DISCUSSION AND QUALIFICATION OF FIRE EFFECT:

A May wildfire killed 60 to 70 percent of sheoak in Florida [10]. A

smoldering controlled burn in Florida killed 90 percent of the sheoaks

on the study plot [14]. A second attempt in the same area killed

all the sheoaks; trunk diameters were between 5 and 8 inches (13-20 cm).

Another tree, with a d.b.h. of 2 feet (0.66 m), was killed after

charcoal was left to smolder at its base [14].

PLANT RESPONSE TO FIRE:

Trees less than 3 inches (8 cm) in diameter may sprout following fire.

Trees larger than this usually die [3,14].

FIRE MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

Periodic fires coupled with the use of herbicides may be an effective

method of controlling sheoak. However, too frequent, intense

fires that kill overstory native pines may actually encourage Casuarina

species to establish [18]. Morton [14] warns that burning Australian

pine in peat soils may be hazardous. Elfer [3] suggests that fire may

be an effective control method for trees greater than 3 inches (8 cm) in

diameter and in dense stands. Burning could be potentially harmful if

the soil pH is changed such that native species cannot establish [3].

REFERENCES

SPECIES: Casuarina spp.

REFERENCES:

1. Bernard, Stephen R.; Brown, Kenneth F. 1977. Distribution of mammals,

reptiles, and amphibians by BLM physiographic regions and A.W. Kuchler's

associations for the eleven western states. Tech. Note 301. Denver, CO:

U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. 169 p.

[434]

2. Cole, Tomas G.; Whitesell, Craig D.; Falanruw, Marjore C.; MacLean, Colin D.;

[and others]. 1987. Vegetation survey of the Republic of Palau. Res. Bull.

PSW-22. Berkeley, CA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service,

Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Experiment Station. 13 p. [16147]

3. Elfers, Susan C. 1988. Casuarina equisetifolia. Unpublished report

prepared for The Nature Conservancy on Australian pine. Winter Park, FL:

The Nature Conservancy. 14 p. On file at: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire

Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT. [17376]

4. Eyre, F. H., ed. 1980. Forest cover types of the United States and

Canada. Washington, DC: Society of American Foresters. 148 p. [905]

5. Falanruw, Marjorie C.; Cole, Thomas G.; Ambacher, Alan H. 1989.

Vegetation survey of Rota, Tinian, and Saipan, Commonwealth of the

Northern Mariana Islands. Resource Bulletin PSW-27. Berkeley, CA: U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research

Station. 11 p. [15707]

6. Falanruw, Marjorie C.; Maka, Jean E.; Cole, Thomas G.; Whitesell, Craig

D. 1990. Common and scientific names of trees and shrubs of Mariana,

Caroline, and Marshall Islands. Resource Bulletin PSW-26. Berkeley, CA:

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest

Research Station. 91 p. [15706]

7. Flores, Eugenia M. 1980. Shoot vascular system and phyllotaxis of

Casuarina (Casuarinaceae). American Journal of Botany. 67(2): 131-140.

[17373]

8. Garrison, George A.; Bjugstad, Ardell J.; Duncan, Don A.; [and others].

1977. Vegetation and environmental features of forest and range

ecosystems. Agric. Handb. 475. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service. 68 p. [998]

9. Klukas, Richard W. 1973. Control burn activities in Everglades National

Park. In: Proceedings, annual Tall Timbers fire ecology conference; 1972

June 8-9; Lubbock, TX. Number 12. Tallahassee, FL: Tall Timbers Research

Station: 397-425. [8476]

10. Klukas, Richard W. 1969. The Australian pine problem in Everglades

National Park. Part 1. The problem and some solutions. Internal Report.

South Florida Research Center, Everglades National Park. 16 p.On file

with: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain

Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT. [17375]

11. Kuchler, A. W. 1964. Manual to accompany the map of potential vegetation

of the conterminous United States. Special Publication No. 36. New York:

American Geographical Society. 77 p. [1384]

12. Little, Elbert L., Jr.; Skomen, Roger G. 1989. Common forest trees of

Hawaii (native and introduced). Agric. Handb. 679. Washington, DC: U.S

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 321 p. [9433]

13. Lyon, L. Jack; Stickney, Peter F. 1976. Early vegetal succession

following large northern Rocky Mountain wildfires. In: Proceedings, Tall

Timbers fire ecology conference and Intermountain Fire Research Council

fire and land management symposium; 1974 October 8-10; Missoula, MT. No.

14. Tallahassee, FL: Tall Timbers Research Station: 355-373. [1496]

14. Morton, Julia F. 1980. The Australian pine or beefwood (Casuarina

equisetifolia L.), an invasive "weed" tree in Florida. In: Proceedings,

Florida State Horticultural Society. 93: 87-95. [17343]

15. Raunkiaer, C. 1934. The life forms of plants and statistical plant

geography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 632 p. [2843]

16. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2018. PLANTS Database,

[Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service

(Producer). Available: https://plants.usda.gov/ [34262]

17. Vietmeyer, Noel. 1986. Casuarina: weed or windfall?. American Forests.

Feb: 22-26; 63. [17345]

18. Wade, Dale; Ewel, John; Hofstetter, Ronald. 1980. Fire in South Florida

ecosystems. Gen. Tech. Rep. SE-17. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station. 125

p. [10362]

19. Wunderlin, Richard P. 1998. Guide to the vascular plants of Florida.

Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. 806 p. [28655]

FEIS Home Page