Index of Species Information

SPECIES: Hamamelis virginiana

|

|

|

| American witchhazel. Creative Commons image by James H. Miller & Ted Bodner, Southern Weed Science Society, Bugwood.org. |

Introductory

SPECIES: Hamamelis virginiana

AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION:

Coladonato, Milo. 1993. Hamamelis virginiana. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station,

Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available:

https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/tree/hamvir/all.html [].

Updates: On 29 January 2018, the common name of the species was changed in FEIS from: witch-hazel

to: American witchhazel. Photos and the map were also added.

ABBREVIATION:

HAMVIR

SYNONYMS:

Hamamelis virginiana var. parvifolia Nutt. [3], prarie peninsula

SCS PLANT CODE:

HAVI4

COMMON NAMES:

American witchhazel

witch-hazel

TAXONOMY:

The scientific name for American witchhazel is Hamamelis virginiana L. [24].

LIFE FORM:

Tree, Shrub

FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS:

No special status

OTHER STATUS:

NO-ENTRY

DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE

SPECIES: Hamamelis virginiana

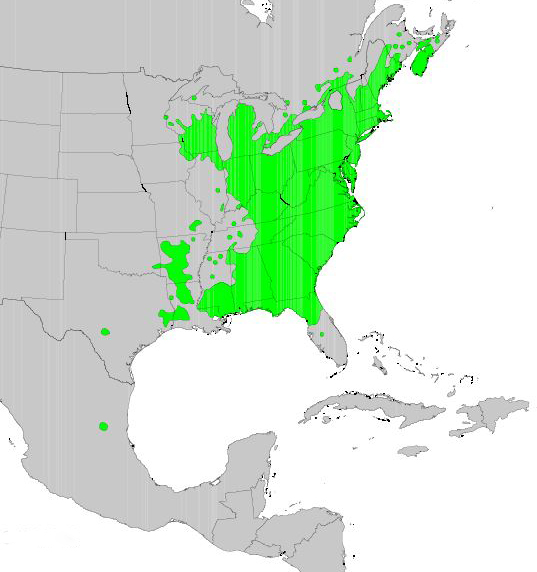

GENERAL DISTRIBUTION:

American witchhazel occurs throughout the northeastern and southeastern United

States. It extends from the Appalachian Mountains south to the northern

Florida Panhandle and west from the mountains into Indiana, Illinois,

Iowa, Minnesota, western Kentucky, eastern Missouri, eastern Oklahoma,

and eastern Texas. At its northern limit, American witchhazel ranges along the

southern border of Canada from southern Ontario to southern Nova Scotia.

Isolated populations occur in south-central Texas and east-central Mexico at its

southern limit [3,12,25,32,40].

|

| Distribution of American witchhazel. 1977 USDA, Forest Service map digitized by Thompson and others [40]. |

ECOSYSTEMS:

FRES10 White - red - jack pine

FRES11 Spruce - fir

FRES12 Longleaf - slash pine

FRES13 Loblolly - shortleaf pine

FRES14 Oak - pine

FRES15 Oak - hickory

FRES18 Maple - beech - birch

STATES:

AL AR CT DE FL GA IL IN IA KY

LA ME MD MA MI MN MS MO NH NJ

NY NC OH OK PA SC TN TX VT VA

WV NB NS ON PQ

BLM PHYSIOGRAPHIC REGIONS:

NO-ENTRY

KUCHLER PLANT ASSOCIATIONS:

K095 Great Lakes pine forest

K096 Northeastern spruce - fir forest

K097 Southeastern spruce - fir forest

K100 Oak - hickory forest

K101 Elm - ash forest

K102 Beech - maple forest

K104 Appalachian oak forest

K106 Northern hardwoods

K111 Oak - hickory - pine forest

K112 Southern mixed forest

K113 Southern floodplain forest

SAF COVER TYPES:

14 Northern pin oak

17 Pin cherry

19 Gray birch - red maple

20 White pine - northern red oak - red maple

21 Eastern white pine

22 White pine - hemlock

23 Eastern hemlock

24 Hemlock - yellow birch

25 Sugar maple - beech - yellow birch

28 Black cherry - maple

31 Red spruce - sugar maple - beech

32 Red spruce

40 Post oak - blackjack oak

42 Bur oak

43 Bear oak

44 Chestnut oak

45 Pitch pine

51 White pine - chestnut oak

52 White oak - black oak - northern red oak

53 White oak

55 Northern red oak

57 Yellow-poplar

59 Yellow-poplar - white oak - northern red oak

60 Beech - sugar maple

62 Silver maple - American elm

64 Sassafras - persimmon

75 Shortleaf pine

79 Virginia pine

80 Loblolly pine - shortleaf pine

81 Loblolly pine

82 Loblolly pine - hardwood

83 Longleaf pine - slash pine

93 Sugarberry - American elm - green ash

97 Atlantic white-cedar

108 Red maple

110 Black oak

SRM (RANGELAND) COVER TYPES:

NO-ENTRY

HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES:

NO-ENTRY

MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

SPECIES: Hamamelis virginiana

IMPORTANCE TO LIVESTOCK AND WILDLIFE:

The fruit of American witchhazel is eaten by ruffed grouse, northern bobwhite,

ring-necked pheasant, and white-tailed deer. The fruit is also

frequently eaten by beaver and cottontail rabbit [11,35].

American witchhazel fruit is a minor fall food for black bear in western

Massachusetts [15].

PALATABILITY:

NO-ENTRY

NUTRITIONAL VALUE:

NO-ENTRY

COVER VALUE:

NO-ENTRY

VALUE FOR REHABILITATION OF DISTURBED SITES:

NO-ENTRY

OTHER USES AND VALUES:

Medicinal extracts, lotions, and salves are prepared from the leaves,

twigs, and bark of American witchhazel. The distillate is used to reduce

inflammation, stop bleeding, and check secretions of the mucous

membranes. Extracts of the twigs were also believed to infuse the

imbiber with occult powers [36,37].

OTHER MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

American witchhazel competes with more desirable hardwoods for available light

and moisture [26]. Its dense cover inhibits seed germination of

intolerant species [9].

Blair and Burnett [2] reported that American witchhazel, along with Carolina

jessamine (Gelsemium sempervirens), blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), sweetgum

(Liquidambar styraciflua), red maple (Acer rubrum), and post oak

(Quercus stellata), declined by 94.7 percent collectively after logging.

BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS

SPECIES: Hamamelis virginiana

GENERAL BOTANICAL CHARACTERISTICS:

American witchhazel is a deciduous shrub or small tree with a short trunk,

bearing numerous spreading, crooked branches. At maturity, it is

commonly 15 to 25 (4.5-7.5 m) feet tall. It has thin bark and shallow

roots. The fruit is a woody capsule containing two to four seeds

[19,20,21,23].

|

| American witchhazel flower. Creative Commons image by Vern Wilkins, Indiana University, Bugwood.org. |

RAUNKIAER LIFE FORM:

Phanerophyte

REGENERATION PROCESSES:

American witchhazel reproduces mainly by seed. After maturing the capsules

burst open, explosively discharging their seeds several yards from the

parent plant. There is limited dispersal by birds. The seeds germinate

the second year after dispersal [5,29]. Brinkman [4] reported that

American witchhazel can be propagated by layering.

SITE CHARACTERISTICS:

American witchhazel is found on a variety of sites but is most abundant in mesic

woods and bottoms. In the western and southern parts of its range, it

is confined to moist cool valleys, moist flats, north and east slopes,

coves, benches, and ravines. In the northern part of its range, it is

found on drier and warmer sites of slopes and hilltops [1,6,8,27].

In addition to those species listed under Distribution and Occurrence,

common tree and shrub associates of American witchhazel include white ash

(Fraxinus americana), blackgum, mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia),

blueberry (Vaccinium spp.), rhododendron (Rhododendron spp.), pepperbush

(Clethra acuminata), sweetgum, flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), and

eastern hophornbeam (Ostrya virginiana) [6,7,20,30].

SUCCESSIONAL STATUS:

American witchhazel is a shade-tolerant, mid- to late-seral species. It

sometimes forms a solid understory in second-growth and old-growth

forests in the eastern United States [9,13,14].

SEASONAL DEVELOPMENT:

The flowers of American witchhazel open in September and October, and the fruit

ripens the next fall. Shortly after ripening, the capsules burst open,

discharging their seed [4,5].

FIRE ECOLOGY

SPECIES: Hamamelis virginiana

FIRE ECOLOGY OR ADAPTATIONS:

DeBruyn and Buckner [10] rated American witchhazel low in fire resistance. This

is probably due to its thin bark, shallow roots, and low-branching

habit. Fire survival strategies were not given.

FIRE REGIMES:

Find fire regime information for the plant communities in which this

species may occur by entering the species name in the FEIS home page under

"Find Fire Regimes".

POSTFIRE REGENERATION STRATEGY:

Secondary colonizer - off-site seed

FIRE EFFECTS

SPECIES: Hamamelis virginiana

IMMEDIATE FIRE EFFECT ON PLANT:

American witchhazel is readily killed by fire. In a prescribed fire in a

loblolly pine community in western Tennessee, witch hazel suffered 54

percent mortality [10].

DISCUSSION AND QUALIFICATION OF FIRE EFFECT:

NO-ENTRY

PLANT RESPONSE TO FIRE:

American witchhazel's response to fire is not well documented. Literature

suggests that it is generally a fire decreaser, although pre- and

postfire/unburned control comparisions were unavailable as of 1993

[17,31,38].

DISCUSSION AND QUALIFICATION OF PLANT RESPONSE:

On the George Washington National Forest, West Virginia, a spring prescribed

fire increased American witchhazel seedling density in a mixed-hardwood forest.

Average American witchhazel seedling densities before fire and in postfire year 5

were 290 and 365 seedlings/acre, respectively; American witchhazel sprout densities

were 395 sprouts/acre before and 184 sprouts/acre 5 years after the fire.

See the Research Paper of Wendel and Smith's [39] study for details on

the fire prescription and fire effects on American witchhazel and 6 other tree

species.

The following Research Project Summaries provide information on prescribed

fire use and postfire response of plant community species, including

American witchhazel, that was not available when this species review was originally

written:

FIRE MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

NO ENTRY

REFERENCES

SPECIES: Hamamelis virginiana

REFERENCES:

1. Adams, Harold S.; Stephenson, Steven L. 1989. Old-growth red spruce

communities in the mid-Appalachians. Vegetatio. 85: 45-56. [11409]

2. Blair, Robert M.; Brunett, Louis E. 1976. Phytosociological changes

after timber harvest in a southern pine ecosystem. Ecology. 57: 18-32.

[9646]

3. Braun, E. Lucy. 1961. The woody plants of Ohio. Columbus, OH: Ohio State

University Press. 362 p. [12914]

4. Brinkman, Kenneth A. 1974. Hamamelis virginiana L. witch-hazel. In:

Schopmeyer, C. S., ed. Seeds of woody plants in the United States.

Agric. Handb. 450. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Forest Service: 443-444. [7679]

5. Chapman, William K.; Bessette, Alan E. 1990. Trees and shrubs of the

Adirondacks. Utica, NY: North Country Books, Inc. 131 p. [12766]

6. Core, Earl L. 1929. Plant ecology of Spruce Mountain, West Virginia.

Ecology. 10(1): 1-13. [9218]

7. Crawford, Hewlette S.; Hooper, R. G.; Harlow, R. F. 1976. Woody plants

selected by beavers in the Appalachian Ridge and Valley Province. Res.

Pap. NE-346. Upper Darby, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest

Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station. 6 p. [20005]

8. Cross, Shirley G. 1992. An indigenous population of Clintonia borealis

(Liliaceae) on Cape Cod. Rhodora. 94(877): 98-99. [18125]

9. Curtis, John T. 1959. The vegetation of Wisconsin. Madison, WI: The

University of Wisconsin Press. 657 p. [7116]

10. de Bruyn, Peter; Buckner, Edward. 1981. Prescribed fire on sloping

terrain in west Tennessee to maintain loblolly pine (Pinus taeda). In:

Barnett, James P., ed. Proceedings, 1st biennial southern silvicultural

research conference; 1980 November 6-7; Atlanta, GA. Gen. Tech. Rep.

SO-34. New Orleans, LA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service,

Southern Forest Experiment Station: 67-69. [12091]

11. Della-Bianca, Lino; Johnson, Frank M. 1965. Effect of an intensive

cleaning on deer-browse production in the southern Appalachians. Journal

of Wildlife Management. 29(4): 729-733. [16404]

12. Duncan, Wilbur H.; Duncan, Marion B. 1987. The Smithsonian guide to

seaside plants of the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts from Louisiana to

Massachusetts, exclusive of lower peninsular Florida. Washington, DC:

Smithsonian Institution Press. 409 p. [12906]

13. Downs, Julie A.; Abrams, Marc D. 1991. Composition and structure of an

old-growth versus a second-growth white oak forest in southwestern

Pennsylvania. In: McCormick, Larry H.; Gottschalk, Kurt W., eds.

Proceedings, 8th central hardwood forest conference; 1991 March 4-6;

University Park, PA. Gen. Tech. Rep. NE-148. Radnor, PA: U.S. Department

of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station:

207-223. [15313]

14. Eggler, Willis A. 1938. The maple-basswood forest type in Washburn

County, Wisconsin. Ecology. 19(2): 243-263. [6907]

15. Elowe, Kenneth D.; Dodge, Wendell E. 1989. Factors affecting black bear

reproductive success and cub survival. Journal of Wildlife Management.

53(4): 962-968. [10339]

16. Eyre, F. H., ed. 1980. Forest cover types of the United States and

Canada. Washington, DC: Society of American Foresters. 148 p. [905]

17. Fennell, Norman H.; Hutnik, Russell J. 1970. Ecological effects of

forest fires. Unpublished paper on file at: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire

Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT. 84 p. [16873]

18. Garrison, George A.; Bjugstad, Ardell J.; Duncan, Don A.; [and others].

1977. Vegetation and environmental features of forest and range

ecosystems. Agric. Handb. 475. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service. 68 p. [998]

19. Godfrey, Robert K. 1988. Trees, shrubs, and woody vines of northern

Florida and adjacent Georgia and Alabama. Athens, GA: The University of

Georgia Press. 734 p. [10239]

20. Gleason, Henry A.; Cronquist, Arthur. 1991. Manual of vascular plants of

northeastern United States and adjacent Canada. 2nd ed. New York: New

York Botanical Garden. 910 p. [20329]

21. Hosie, R. C. 1969. Native trees of Canada. 7th ed. Ottawa, ON: Canadian

Forestry Service, Department of Fisheries and Forestry. 380 p. [3375]

22. Kuchler, A. W. 1964. Manual to accompany the map of potential vegetation

of the conterminous United States. Special Publication No. 36. New York:

American Geographical Society. 77 p. [1384]

23. Kudish, Michael. 1992. Adirondack upland flora: an ecological

perspective. Saranac, NY: The Chauncy Press. 320 p. [19376]

24. Little, Elbert L., Jr. 1979. Checklist of United States trees (native

and naturalized). Agric. Handb. 541. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service. 375 p. [2952]

25. Marquis, David A. 1990. Prunus serotina Ehrh. black cherry. In: Burns,

Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H., technical coordinators. Silvics of

North America. Volume 2. Hardwoods. Agric. Handb. 654. Washington, DC:

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: 594-604. [13972]

26. McGee, Charles E.; Hooper, Ralph M. 1970. Regeneration after

clearcutting in the southern Appalachians. Res. Pap. SE-70. Asheville,

NC: U.S. Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment

Station. 12 p. [10886]

27. McGinnes, Burd S.; Ripley, Thomas H. 1962. Evaluation of wildlife

response to forest-wildlife management--a preliminary report. In:

Southern forestry on the march: Proceedings, Society of American

Foresters meeting; [Date of conference unknown]; Atlanta, GA. [Place of

publication unknown]. [Publisher unknown]. 167-171. [16735]

28. Raunkiaer, C. 1934. The life forms of plants and statistical plant

geography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 632 p. [2843]

29. Roland, A. E.; Smith, E. C. 1969. The flora of Nova Scotia. Halifax, NS:

Nova Scotia Museum. 746 p. [13158]

30. Schlesinger, Richard C. 1990. Fraxinus americana L. white ash. In:

Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H., technical coordinators. Silvics

of North America. Vol. 2. Hardwoods. Agric. Handb. 654. Washington, DC:

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: 333-338. [13965]

31. Silker, T. H. 1957. Prescribed burning in the silviculture and

management of southern pine-hardwood and slash pine stands. In: Society

of American Foresters: Proceedings of the 1956 annual meeting; [Date of

conference unknown]; [Location of conference unknown]. Washington, DC:

Society of American Foresters: 94-99. [15279]

32. Soper, James H.; Heimburger, Margaret L. 1982. Shrubs of Ontario. Life

Sciences Misc. Publ. Toronto, ON: Royal Ontario Museum. 495 p. [12907]

33. Stickney, Peter F. 1989. Seral origin of species originating in northern

Rocky Mountain forests. Unpublished draft on file at: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire

Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT; RWU 4403 files. 7 p. [20090]

34. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service. 1982.

National list of scientific plant names. Vol. 1. List of plant names.

SCS-TP-159. Washington, DC. 416 p. [11573]

35. Van Dersal, William R. 1938. Native woody plants of the United States,

their erosion-control and wildlife values. Washington, DC: U.S.

Department of Agriculture. 362 p. [4240]

36. Vines, Robert A. 1960. Trees, shrubs, and woody vines of the Southwest.

Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. 1104 p. [7707]

37. Walker, Laurence C. 1991. The southern forest: A chronicle. Austin, TX:

University of Texas Press. 322 p. [17597]

38. Wydeven, Adrian P.; Kloes, Glenn G. 1989. Canopy reduction, fire

influence oak regeneration (Wisconsin). Restoration & Management Notes.

7(2): 87-88. [11413]

39. Wendel, G. W.; Smith, H. Clay. 1986. Effects of a prescribed fire in

a central Appalachian oak-hickory stand. NE-RP-594. Broomall, PA: U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment

Station. 8 p. [73936]

40. Thompson, Robert S.; Anderson, Katherine H.; Bartlein, Patrick J. 1999.

Digital representations of tree species range maps from "Atlas of United

States trees" by Elbert L. Little, Jr. (and other publications). In: Atlas

of relations between climatic parameters and distributions of important trees

and shrubs in North America. Denver, CO: U.S. Geological Survey, Information

Services (Producer). On file at: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service,

Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT; FEIS

files. [92575]

FEIS Home Page