Chapter 2—Planning for Restoration of Small Sites in Wilderness

- 2.1 Gathering the Information To Formulate a Plan

- 2.1.1 Using Your Land Management Plan and NEPA

- 2.1.2 Using the Minimum Requirements Decision Process

- 2.1.3 Planning Scale and Priorities

- 2.1.4 Forming an Interdisciplinary Team

- 2.1.5 Developing a Site Assessment

- 2.1.6 Assessing Historical Human Influences

- 2.1.7 Assessing Current Human Influences

- 2.1.8 Problem Statements

- 2.1.9 Scoping the Proposed Action

- 2.1.10 Selecting Management Actions To Meet Standards

- 2.1.11 The Minimum Tool

- 2.1.12 Types of Management Actions

- 2.1.13 Passive Restoration of Damaged Soil and Vegetation

- 2.1.14 Active Restoration of Damaged Soil and Vegetation

- 2.1.15 Adjusting Management Actions: A Tale of Two Lake Basins

This chapter provides a conceptual overview of the components of restoration planning (figure 2-1) for a wilderness setting with ongoing recreational use. This chapter explains the concepts depicted on the accompanying flowchart, A Process for Small-Site Restoration in Wilderness. Chapter 3, which is more technical, will provide the restoration methodologies. This chapter serves more as the "trail map" to help you see where you are headed. Chapter 3 serves as a guide to help you get there.

Figure 2-1—Restoration planning in the Desolation Wilderness, CA,

considered the Three Es: engineering the project design to succeed,

education

of the public so they know how to reduce wilderness impacts,

and enforcement

of regulations designed to protect the wilderness resource.

Just as there is usually more than one right way to travel to a destination, the process laid out in this chapter may not occur in exactly the same order in all restoration projects. That's the wilderness restoration experience!

The flowchart, developed by Tom Carlson of the Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center and others, was revised by Lisa Therrell.

Click on image for large and descriptive view

As can be seen from the flowchart, A Process for Small-Site Restoration in Wilderness, many factors must be considered during the restoration planning. Law, policy, and land management plans provide sideboards and the desired conditions for the land. A site assessment examines the role of historical and continuing influences, leading to proposed management actions. Designing a holistic package of management actions helps support restoration success.

2.1.1 Using Your Land Management Plan and NEPA

Most agencies manage wilderness and backcountry areas according to management direction provided in a land management plan. The management plan, tiered to law and policy, provides clear goals, objectives, and management standards that steer wilderness management. Development of a restoration project, as with any project on Federal land, also needs to follow the procedures mandated by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). In this chapter, we will show how to dovetail restoration planning with the NEPA process.

Many Forest Service and U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management (BLM) wildernesses use the accompanying Limits of Acceptable Change (LAC) model (Stankey and others 1985) to formulate management direction. The U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service uses the accompanying Visitor Experience and Resource Protection (VERP) framework (U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service 1993) for planning. Both planning systems include the concept of zones governed by indicators of condition. Management actions are selected to achieve desirable resource conditions, while preserving an appropriate social setting.

Click on image for

large and descriptive view

Resource conditions are monitored to determine when management actions might be needed. Restoration treatments often are considered because recreation-related campsite condition indicators such as vegetation loss, campsite density, or a site's distance from a trail or water do not comply with the management plan. Other campsite condition indicators may be based on social concerns, such as whether campers in one site can see and hear campers in another site (such sites are said to be intervisible and interaudible). These indicators are likely to have quantitatively measurable standards. Qualitative standards also may come into play, such as indicators describing the degree of naturalness or those describing the overall visual setting. Indicators based on other resources may drive the need for action. For example, such indicators might be based on riparian condition, unique plant communities, or soil degradation.

Once monitoring for an area has been completed, managers analyze whether conditions in the area comply with the standards for that zone or opportunity class (using LAC terminology). If standards are being met, current management direction may be appropriate; restoration doesn't need to be considered (See the flowchart, A Process for Small-Site Restoration in Wilderness, at the beginning of this chapter). If conditions in the area do not comply with management standards, revised management actions are needed. Vegetative restoration may, or may not, be part of the mix of possible solutions.

Click on image for

large and descriptive view

2.1.2 Using the Minimum Requirements Decision Process

If a proposed project is in congressionally designated wilderness, the first step is to ask the question-"Is administrative action needed?" This question is the first step in the Minimum Requirements Decision process, developed to ensure compliance with the intent of the Wilderness Act and agency policies. The Minimum Requirements Decision Guide is available from the Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center (Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center 2004) and on the Internet at http://www.wilderness.net. Worksheets in the guide will lead you through the minimum requirements decision process.

To oversimplify the minimum requirements concept, administrative action in wilderness is "required" when necessary to achieve the purposes of the Wilderness Act, such as:

- Allowing for natural processes, solitude, and primitive and unconfined

recreation

- Ensuring a lack of human manipulation and permanent structures

- Providing

for provisional uses of wilderness, such as valid existing rights

- Addressing emergencies

2.1.3 Planning Scale and Priorities

Planning scale also needs to be determined. Many of the national parks have developed programmatic vegetation restoration management plans covering the entire park. The Rocky Mountain National Park Vegetation Restoration Management Plan, version 2, 2006, is one example. This approach allows managers to look at all human-caused disturbances, define parkwide goals and objectives, and sort out priorities and procedures at a large scale. Individual projects are selected based on priorities. Selected projects receive site-specific planning.

It doesn't make much sense to go through the entire planning process for one campsite. On the other hand, if the plan includes too large an area, such as an entire watershed, the site-specific planning required for a successful plan (and required by NEPA) might become unmanageable.

One suggestion is to focus on one destination or trail, or on closely interrelated areas. For example, planning might be more efficient if you consider restoration of nearby campsites when planning a trail relocation and restoration project. A number of wilderness projects have employed this strategy quite successfully. The planning area should be large enough (figure 2-2) to address the problems created when users are displaced to other areas nearby.

Figure 2-2-The planning scale should be large enough to

address

problems

that

arise when users are being displaced from closed areas.

Determining which projects receive priority depends on resource management objectives, conditions in the planning area, budgets, and compatible opportunities. It would be easy to say that the most serious problem should be your first priority. But there may be too many constraints to solve the most serious problem right away. The constraints may be financial, biological, logistical, financial, or political. For your first projects, consider choosing ones where your chances of success are fairly high. Another approach would be to choose projects that address small pieces of a complex problem. As you learn from your successes, you can move on to more challenging projects.

2.1.4 Forming an Interdisciplinary Team

Persons knowledgeable about any resources potentially affected by a proposed project need to be included on an interdisciplinary team. At a minimum, a typical Forest Service team would include the recreation or wilderness manager, an archeologist or cultural resource technician, a botanist, and a soil scientist (figure 2-3). Additional support may be needed from a landscape architect, wildlife biologist, fisheries biologist, hydrologist, engineer, or trails specialist. The team will identify and gather any additional resource data or visitor-use data needed.

Figure 2-3—An interdisciplinary team field trip will help

build

a mutual understanding of human-caused

impacts and viable solutions.

2.1.5 Developing a Site Assessment

The next step is to develop a more detailed assessment of the planning area. The purpose of the site assessment (figure 2-4) is to gather the information for a clear problem statement and site-specific proposed action. A quick initial assessment may be followed by a more exhaustive assessment. During the site assessment process, you will gather all the information needed to formulate the preferred alternative (NEPA terminology) and write a detailed restoration plan. The restoration plan also will include other supporting management actions.

Figure 2-4-Restorationists Joy Juelson and Greg Shannon

collaborate on a site

assessment for Juelson's research

project in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness,

WA.

The next chapter will provide technical background to help you evaluate erosion, soil, and vegetative conditions as part of your site assessment. The remainder of this chapter will help you identify and correct problems caused by human use, so your plan can address not just the problems, but their causes.

2.1.6 Assessing Historical Human Influences

The team will determine the initial and ongoing causes of resource impacts. Don't assume that the impacts you see today are from current recreation use patterns-take enough time to research past uses of the area that may have contributed to current conditions. Even if a specific use ended long ago, you will want to understand the full context of impacts caused by human use. This research also will help identify cultural sites you may not wish to disturb with a restoration project.

Historical influences might include grazing, old sheep camps, use by large groups, old developments such as roads or mines, logging (yes, even in wilderness), homesteads, administrative sites, airfields, or damage by off-road vehicles. In some cases, an area may continue to erode or noxious weeds may continue to spread, even after the original cause of the problem has been eliminated.

Your staff archeologist may help you find relevant information sources. You may wish to consult agency heritage resource files, range records, local historical libraries, local history books or memoirs, and expedition journals. Local residents, oldtimers at your work unit, and former employees also are excellent sources of information.

One week, I hiked to Lake Mary in Washington's Alpine Lakes Wilderness, joining the restoration crew to plant a site we had designed as an experiment to test the effectiveness of inoculating planting holes with mycorrhizal fungi (figure 2-5). Working together, we were planting specific numbers of several species in a grid pattern, mixing a spoonful of inoculum into half the planting holes. While we were planting the site with greenhouse-grown stock, I was surprised to feel a very sharp angular chip of stone that was not characteristic of the powdery ash-based soil. Taking a close look, I recognized the tiny chip as a lithic flake—a byproduct of making arrowheads. A thoughtful debate on whether to stop or continue our work followed. Because the site had already been disturbed with a restoration treatment 10 years before, we continued our work. This taught me the importance of making sure an archeologist or cultural resource technician visits each site before treatment.

—Lisa Therrell

Figure 2-5-Inoculating planting holes with mycorrhizal fungi.

2.1.7 Assessing Current Human Influences

Impacts may be declining because of changes in use. Perhaps conditions have stabilized to a new norm. Thorough observation and analysis of current human use patterns is essential. The restorationist or wilderness manager needs to be part psychologist or sociologist, gaining a feel for the management tactics that might succeed or fail based on an understanding of the local clientele. Future management actions will be based, in part, on these determinations.

Identify the regulations that are in place. How are these regulations helping your situation? How might they be making things worse? Are additional regulations or adjustments needed?

Look for situations where management direction or regulations do not complement the indicators or standards, resulting in noncompliance. For example, the Alpine Lakes Wilderness in Washington has a campsite vegetation loss standard of 400 square feet (about 37 square meters) or less. The group size limit, including stock, is 12. Groups of 12, especially those with stock, occupy and impact larger areas than allowed by the standards. In fact, any group with a large wall tent will impact more vegetation than allowed by the 400-square-foot (about 37-square-meter) standard. Such discrepancies need to be addressed during the planning process.

It is helpful to think of the larger project as a series of miniprojects. Assign each campsite and trail segment (or other feature) a unique number, cross-referenced to a map (figure 2-6). The number allows each feature to be tracked all the way through planning, implementation, and monitoring. The project area map needs to be detailed enough that each campsite and trail segment can be identified on the ground. Be sure to indicate key features such as north, the direction of waterflow, system trails, the direction to system trails, and so forth. It may not be possible to map every single social trail at this scale; more detailed site maps will show the trails. Establish photopoints, so you can use a series of pictures of impacted campsites and trails to show changes in their condition. Your numbering system will allow you to identify each site.

Figure 2-6—One example of a project map.

It pays to study human use patterns in an area. Hang out and watch what people do during peak-use periods and during different parts of the use season.

- Who are

the users?

- Where do users wander when they select a campsite?

- Which

campsites receive the most use?

- Are all campsites occupied during

peak-use periods?

- Does campsite occupancy change use patterns

(forcing visitors to bypass the occupied sites when accessing areas

of interest, for example)?

- Do groups avoid camping in campsites

that have impacts?

- How and where do users access water, firewood,

and toilet areas?

- How do fishing and other area attractions affect

trail and campsite development?

- What other seasonal conditions

influence use patterns? High water? Seasonal snowmelt? Presence

or lack of shade during the hot months? Access to water?

- How do current regulations and other management strategies shape these patterns?

Review use statistics for the area. Are use levels stable, rising, or falling? Have the types of users changed over time?

What behaviors, use levels, or conditions need to change to bring the planning area back into compliance with standards or management objectives?

Each specialist will contribute to the assessment based on his or her discipline. Chapter 3 discusses a process and method for completing a soil and vegetation assessment. Assuming that restoration might be part of a proposed action, the focus is on comparing the damaged sites to one or more reference sites to determine what is missing and what can realistically be restored.

The information gathered for the site assessment is quite specific. Plant species and the distribution of native plant communities are noted. Potential site treatments are based on soils, vegetation, and use patterns. An archeologist or cultural resource technician needs to survey any sites that might be slated for ground disturbance or another action that might affect heritage resources. Native sources of plant material, rock, and quantities of nearby fill are noted.

In short, any factors that could limit project success are identified. Appendix A, Treatments To Manage Factors Limiting Restoration, lists potential factors that limit restoration success, along with the corresponding treatments.

For any wilderness with winter snow cover, the early-season snowmelt is a pivotal time for assessing impacts. When the ground is partially covered with snow, visitors will select campsites and travel routes differently than when the ground is bare. They may walk or camp on vegetation because they can't find the main trail and camps, forming duplicate sites and trails (figures 2-7a and 7b). Restorationists will want to avoid closing the first trails and camps that become snowfree. Document your findings with photos and maps.

Figure 2-7a—Would you believe that the Pacific Crest

Trail could

still be covered with snow on Labor Day weekend?

Figure 2-7b-Two additional trails were formed to

skirt the snow. This problem

can be avoided with

careful planning, but you have to survey conditions

in

the early season when the snow is beginning to

melt off trails and camps.

2.1.8 Problem Statements

It is helpful to write a problem statement to focus planning. This brief statement includes the location of the project, description of the impacts addressed by the project, causes of the impacts, the magnitude of the impacts, and any special considerations. A sample problem statement would be:

The project area is on the south shore of Cradle Lake (figure 2-8), between Trail No. 1550 and the lake. It involves two campsites, totaling about 4,000 square feet (about 372 square meters), six social trails, and an area where horses are tied for short periods. These sites are now the best options for camping with stock at Cradle Lake, even though they are inside the 200-foot (about 61-meter) setback where camping is not allowed. Cradle Lake also has a 200-foot (about 61-meter) campfire setback from the lakeshore. Illegal fires and stock camping continue to be a problem. Campsite sizes do not conform to standards. The campsites and social trails, highly visible from most portions of the lake basin, are not in conformance with visual standards.

Figure 2-8-Cradle Lake in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness, WA.

2.1.9 Scoping the Proposed Action

Fairly early in the interdisciplinary process, the team will formulate a proposed action (NEPA terminology) describing the purpose for the proposed project, the project location, and the types of actions that might be taken. At this point, the proposed action is specific to a particular area, but doesn't go into excruciating detail. For example, enumerate exactly which campsites will be closed for restoration. The proposed action is included in a letter and mailed to the concerned public as a part of scoping for the NEPA process. Scoping is the stage when concerns about the proposed action and possible mitigating measures are identified.

Based on the Cradle Lake example, a proposed action might look like this:

The proposed action includes the following strategies:

- Relocate Trail

No. 1550 to a more durable location through talus on the other side of

the lake.

- Retain the portion of the old system trail needed to provide lakeshore

access.

- Restore the portion of the old system trail where it leaves

the lake to climb toward the pass.

- Close and restore the two large lakeshore

campsites.

- Direct users to camp on benches away from the lake and at

a nearby stock camp.

- Close four of six social trails.

- Harden the two remaining social trails to provide durable lakeshore access.

Your agency may have a standard scoping mailing list. Work with your team to identify other interested parties, such as local user groups, wilderness advocates, native plant societies, or outfitters and guides. Your scoping process also may include public meetings, club meetings, field trips, articles for newsletters, or press releases. You may need to contact representatives of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or the National Marine Fisheries Service. They are expected to consult on the project if threatened or endangered species or their habitats could be affected.

2.1.10 Selecting Management Actions To Meet Standards

During this stage of planning, your team will identify the appropriate management actions needed to help the planning area meet wilderness standards or other applicable standards. Even though we often start a planning process with restoration in mind, don't assume that restoration is the answer. Other options may be more desirable or appropriate. The process of selecting the best management actions begins with studying the range of options, then choosing options that best complement each other to form an appropriate holistic solution. Even though it is tempting to rush ahead to plan a restoration project, back up a few steps to ensure that you have considered all options.

You have already determined that administrative action is necessary, the first step of the Minimum Requirements Decision Guide (Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center 2004). The next step is to determine the minimum tool. This step requires answering four questions.

- What

are the alternative methods for solving the problem?

- What are the effects

and benefits of each method?

- What is the minimum tool and the rationale

for its selection?

- What operating requirements will minimize impacts?

This section will discuss the first three questions.

Sometimes the concepts of "primitive tool" and "minimum tool" are confused. Part of the tradition of wilderness management includes using primitive tools. Essentially, primitive tools are the tools used during the settlement of America. Based on the language of the Wilderness Act, primitive tools don't have motors and don't have wheels (even though the wheel itself is primitive). Our expert use of these tools and techniques preserves a disappearing slice of our heritage, representing one of the enduring cultural and historical benefits of wilderness.

On the other hand, the minimum tool may not be primitive. The minimum tool represents the minimum action necessary, within the context of wilderness values, to meet management direction or to accomplish other administratively necessary activities. The minimum tool may refer to tools, such as a type of saw, drill, or transportation. Or it may refer to actions, such as the degree of signing, regulation, or physical development in wilderness.

At this stage, consider all the available options. Some methods may not appear to be feasible initially, but conduct some research before reaching conclusions.

Management direction and policy will help frame the options that are appropriate. Many wilderness areas are zoned into "opportunity classes" using the LAC process. The types of management actions identified as acceptable in a transition or semiprimitive zone might be considered unacceptable or possibly a last resort in a primitive or pristine zone. For example, obvious barriers and signs to delineate trails and campsites may be appropriate in the transition zone, but those techniques are inappropriate in a pristine zone.

Public support also will shape the selection of management options. In one study of high-use wilderness destinations, visitors showed low support for limiting use and high support for intensive campsite management techniques, including active restoration (Cole and others 1997). A similar study, using an exit survey of persons who had visited heavily impacted wilderness locations, found that 71 percent did not view agency management favorably. When visitors were surveyed after visits to areas with restoration work in progress, 74 percent reported "positive" to "extremely positive" views of management (Flood and McAvoy 2000).

Before beginning a restoration project, contact users or groups that might be displaced by change (figure 2-9). They may suggest a better alternative that addresses public desires and wilderness protection. In the Seven Lakes Basin of the Selway Bitterroot Wilderness, ID, local stock users suggested a number of ideas that allowed continued limited stock use of fragile subalpine lake basins (Walker 2002).

Figure 2-9—"I love this place—We do, too."

These publications will help guide your wilderness impact analysis:

- Minimum Requirements Decision Guide (Arthur Carhart

National Wilderness Training Center 2004)

- Managing Wilderness Recreation

Use: Common

Problems and Potential Solutions (Cole and others 1987)

- The Limits of Acceptable Change (LAC) System for Wilderness Planning (Stankey and others 1985)

2.1.12 Types of Management Actions

The challenge facing wilderness managers is to develop methods of handling problems that not only address the symptoms, but solve the underlying problems. We will need public support for our new tactics. To borrow vernacular from off-highway vehicle managers, we need to address "The Three Es"—engineering, education, and enforcement. We engineer the project's design so it will succeed, we educate to persuade visitors to practice new behaviors, and we enforce regulations when visitors don't comply.

Wilderness research scientist David Cole (Cole and others 1997) suggests three broad categories of management actions for reducing recreation impacts:

- Reducing recreational use

- Changing

visitor behavior with information and education

- Managing sites intensively by controlling recreational use patterns and restoring damaged sites

Each category of actions has strengths and limitations. Your proposed actions are likely to include a mix of these categories of action as you craft a viable management solution.

2.1.12a Reducing Recreational Use

While limiting use is commonly accepted in the national parks, it is generally seen as a draconian measure in national forests. Limiting use may be the only way to stabilize or reverse impacts to soil and vegetation, especially in areas with too few campsites to support the existing overnight use. Limiting use is not only politically unpopular, it could exclude some users from wilderness and may displace users to other areas. The displaced users could increase the environmental and social impacts at those areas.

The large volume of literature on permit systems should be reviewed carefully before considering limits on use. Nonetheless, it is always appropriate to ask whether the level of use is contributing to the problem. If resource impacts cannot be stabilized at current use levels, reducing use becomes a minimum tool.

An indirect method of reducing use is to lengthen the approach to an area-usually by closing a road to lengthen trail access. Many wilderness visitors will oppose the mere suggestion of lengthening access. However, this management action may complement other objectives, such as reducing road mileage for wildlife habitat needs or reducing the costs of road maintenance.

2.1.12b Changing Visitor Behavior With Information and Education

The strategic use of information and education can, over time, change unnecessary or discretionary high-impact behaviors, such as littering or damaging trees. However, intensified educational programs are unlikely to reverse damage to vegetation and ongoing soil erosion. It is difficult for many visitors to grasp the impact of their individual actions. Changes to old ways, such as the tradition of enjoying a campfire, evolve ever so slowly.

If stabilizing or reversing damage to vegetation and soils is a project goal, education can be an important tool, but education alone will not solve the problem. Visitors need to be told the actions they can take to prevent further damage, such as staying in the confines of existing campsites and trails, learning to travel off trail on durable surfaces (rock, snow, or gravel), refraining from having a fire, and not removing any vegetation.

Plan ahead and prepare.

Plan ahead and prepare.

- Travel and camp on durable surfaces.

- Dispose of waste properly.

- Leave what you find.

- Minimize campfire impacts.

- Respect wildlife.

- Be considerate of other visitors. (For more information, visit http://www.lnt.org)

Common methods to convey information include Web sites, brochures, information on maps, trailhead posters, signs at the site, contacts by receptionists, and contacts by wilderness rangers (figure 2-10). If adequate resources are available, a more comprehensive wilderness education program may be designed. A process for wilderness education planning is available at http://www.wilderness.net.

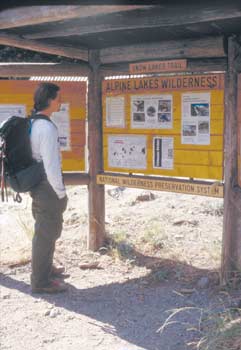

Figure 2-10-Information on bulletin boards can help

visitors learn what's expected

of them in wilderness. Photos

or maps help draw visitors in for a closer look

at the materials.

2.1.12c Intensive Site Management

Intensive site management includes a variety of direct controls: using regulations to require visitors to practice low-impact techniques for wilderness travel, redesigning the area to stabilize impacts and concentrate use, and actively restoring damaged soil and vegetation. The techniques discussed for each of these controls will focus primarily on correcting damage to soil and vegetation. Other problems identified through monitoring and the site assessment process may require additional solutions.

2.1.12d Regulations and Enforcement

Chances are that some regulations may already be in place to reduce impacts to soil and vegetation. Perhaps these regulations have worked in part, but have not allowed the area to reach the appropriate objective for management. It may be necessary to alter regulations or put additional regulations into place. Regulations mandate low-impact behavior in situations where visitors may not normally choose such practices. Regulations are unlikely to succeed without enforcement (figure 2-11).

Figure 2-11—Regulations enforced by rangers can help reduce

damage

caused by visitors in wilderness areas. Regulations might

apply

to the entire

wilderness, to a series of wilderness areas,

or to specific locations.

When considering new regulations or changes to existing regulations, consider the potential that users and their impacts could be displaced. Would this displacement be acceptable? If displaced users meet their needs close by, the impacts will show up close to your project area. They might camp in the next basin over. Perhaps they will seek similar destinations elsewhere or choose another favorite place. Some visitors will seek out completely different wilderness areas, perhaps in other States, where they are less regulated. Visitors displaced from the Enchantment permit area of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness in Washington said they would adopt all strategies discussed above, making it difficult to pinpoint a specific effect of displacement (Shelby and others, no date).

2.1.12e Regulations To Reduce Use Directly

Any regulation may result in an indirect decrease in use if the user would rather go elsewhere than endure the regulation. However, some regulations may reduce overall use directly without actually limiting the number of groups that enter the area. Examples include:

- Limiting

Group Size—A group size limit (for people and/or stock) can be set based

on levels that are sustainable for the campsites, stock-holding areas, and

available forage. Larger groups have more impact, especially when their activities

spread onto vegetated areas and their social interactions require lots of travel

back and forth. Some areas of a wilderness may require a lower group size than

other areas. Regulations limiting group size can be very effective if they

are combined with low-impact practices. Large groups will be displaced to areas

of wilderness that allow larger groups or to other backcountry areas.

- Limiting

Length of Stay—Many national forests already limit the length of stay

(2 weeks is quite common). At a popular destination, a shorter length of stay

may prevent crowding while giving more persons an opportunity to visit.

- Prohibiting

Certain Uses in an Area—An area may be closed to a certain type of use,

such as all stock use, overnight use with stock, or any overnight use altogether.

- Modifying the Location of Use—Some possibilities include requiring the use of designated campsites, prohibiting use at closed sites, or having a camping setback from a lake or desert waterhole.

It is important to have a clear understanding of why a site should be closed. Is it to allow access to a day-use area? To improve the view for others? To reduce campsite intervisibility? To prevent further damage?

Closing a site may or may not fix a problem. Sites are unlikely to recover on their own unless they are impacted only lightly or are located in the lushest of environments. Malcontents may remove signs in closed sites and then say, "We didn't see a sign." Designated sites help concentrate impacts (figure 2-12).

Figure 2-12-Signs telling campers where they're welcome to

camp aren't as likely

to be pulled up and thrown into the

bushes

as signs telling campers where not

to camp.

Designated stock camps and areas to hold stock are an excellent way to concentrate stock impacts.

There is less incentive for campers to remove a sign that designates a campsite, because once the sign is gone they can no longer camp there. Any area that charges a fee for entry incurs more liability for environmental hazards, such as falling trees. If a campsite is designated, forcing a visitor to use it, liability issues may become an increased concern.

Camping setbacks should be considered only when adequate and appropriate places exist to camp outside the setback. Tragically, the number of impacted sites doubled at many wilderness lakes after setbacks were instituted. These sites heal slowly, even with active restoration. Setbacks are common and ecologically important in desert areas where wildlife need undisturbed access to limited water.

Stock setbacks can be used to protect fragile areas, such as shorelines. The national forests in the Washington Cascades implemented a 200-foot (about 61-meter) setback from all lakes and ponds; stock can be within this area only if they are being led to water or passing by on a trail. This practice also reduces user conflicts.

2.1.12f Regulations To Reduce High-Impact Behaviors

Examples of regulations that can be used to reduce or eliminate high-impact behaviors include:

- Prohibiting Campfires—Combined with limiting group size, prohibiting campfires may be the most important regulation to reduce impacts to vegetation and soils. Campfires thoroughly alter soil qualities, making revegetation very difficult. Even in areas where a firepit is considered an acceptable impact, firewood gathering creates many additional impacts. Users create social trails while they are scavenging for wood. The loss of woody debris eliminates habitat for a host of organisms and an important component of the forest floor that contributes to soil development. Trees are damaged as firewood gatherers snap off limbs, creating a human browse line. Large feeder logs in a campfire often remain partially burned. Unless firewood is locally abundant and excess social trails are not a problem, prohibiting campfires (figure 2-13) is a good practice that will reduce impacts over the long term.

Figure 2-13—Campfires may leave scars that are difficult to erase.

- Requiring Low-Impact

Methods for Confining

Stock—Many low-impact alternatives for confining stock eliminate the

need to tie stock to trees (except for short periods). Tying stock to trees

not only destroys vegetation around the tree, but could expose the tree's

roots and girdle the bark, possibly killing the tree. The telltale sign

that a tree has met this fate is a doughnut-shaped depression with a standing

dead tree or stump in the middle. Appropriate use of highlines, hobbles,

pickets,

or electric corrals can prevent this problem. Regulations requiring these

types of stock containment are in place at several wilderness areas, including

the

Lake Chelan-Sawtooth Wilderness and Alpine Lakes Wilderness in Washington.

- Limiting

Campsite Occupancy—Some areas, such as the Mt. Hood Wilderness, regulate

the number of tents or people allowed for a given campsite. This practice

prevents a large group from spilling onto vegetated areas. Nor can a small

group claim a large campsite that is better suited for a large group. Displacement

to other nearby camping areas could become an issue as groups seek a site

for a party of their size.

- Prohibiting Cutting Switchbacks or Leaving

the Trail—Switchback cutting leads to continued erosion and loss

of leaf litter and limbs that often are used to disguise switchback cuts.

A special order can be written to make it illegal to cut switchbacks. Rangers

in some areas with fragile soils or vegetation, such as Paradise Meadows

at Mt. Rainier National Park, cite visitors who leave the trail. With many

thousands

of visitors, this is the only way to stabilize human-caused impacts to

the meadow.

- Modifying Timing of Use—Several methods can be

used to regulate timing of use without instituting a permit system. The

first method is to prohibit certain uses (such as overnight use or grazing)

when the potential for impact is the highest. This may be early in the

season, when vegetation is just emerging, or it may be at another time

to accommodate seasonal wildlife habitat needs. A fee could be charged

during the sensitive time period to discourage use. Another way to discourage

use could be to gate a road and prohibit vehicle access during the sensitive

time period.

- Redesigning Infrastructure To Stabilize Impacts and Concentrate Use—With the possible exception of constructed trails or administrative sites, most impacts at wilderness destinations are caused by the ordinary wear and tear of public use. User trails, often called social trails, generally connect various amenities that visitors are seeking.

Such amenities might include campsites, viewpoints, access to water for drinking or fishing, firewood sources, and private places for toileting. Such a network of trails often looks like the spokes of a wheel, or a spider's web. Users often establish many more trails than are really needed (figure 2-14). Trails shift, depending on snow conditions, wet areas, rockfall, or fallen logs. In addition, trails often shift onto vulnerable locations, such as along the fall line of the slope, which is subject to erosion, or onto areas with fragile vegetation.

Figure 2-14—Multiple trails established by visitors can cause

more

damage

than one carefully located trail. A maze of trails

going every which way is

a common problem in recreation areas.

Most campsites are on relatively flat areas near water. The earliest users (in some cases, indigenous peoples) wanted the best view, which means that many scenic areas have large, denuded, and sometimes eroding campsites. When these sites are occupied, other users may have difficulties reaching the shoreline or campsites nearby.

Good project planning will take into account a variety of criteria that might include:

- Leaving the necessary

infrastructure of social trails and improving them if needed

- Closing

unneeded social trails

- Closing excess campsites, while leaving enough

campsites to meet demand

- Stabilizing or closing eroding trails or

campsites

- Closing or reducing the size of trails or campsites

that do not meet visual objectives

- Closing campsites that are visible

from other campsites

- Closing trails or campsites to protect other

resource values, such as cultural artifacts, rare plants, or animal

habitat

- Installing

barriers to delineate trails and campsites

- Hardening trails or

campsites as needed to concentrate use

- Providing facilities to concentrate use (figure 2-15), such as toilets or facilities to hold stock.

Figure 2-15—The Wallowa toilet design has been used by the Forest

Service since the 1920s. A carefully located toilet helps alleviate

recreation

impact by reducing the number of social trails, by

reducing

vegetation disturbance,

and by protecting water quality.

- Identifying signs that might be needed to inform

the public

- Anticipating the likelihood of public acceptance and the range of possible user behaviors when making these determinations

Methods for implementing these criteria will be discussed in more detail in chapter 3.

2.1.13 Passive Restoration of Damaged Soil and Vegetation

Before concluding that a vegetative restoration treatment is the minimum tool, consider whether natural recovery, or passive restoration, might be successful. Passive restoration allows secondary succession of native plant communities once the conditions preventing vegetative recovery have been abated. Passive restoration has the benefit of allowing Mother Nature to do the healing, producing a more natural result.

Sometimes active restoration may not be necessary once the human impact has been removed. This is especially true in areas:

- That are wet

- That still have live plant material

in the soil

- Where the soil is in good condition to serve as a seedbed

- That have a suitable native seed source nearby

The following criteria favoring passive restoration are based on those used by Rocky Mountain National Park (U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service, Rocky Mountain National Park, 2006):

- The

disturbed site will resemble an early-, mid-, or late-seral condition

for an undisturbed community growing under similar environmental

conditions.

- Adequate native propagules remain in the soil or plants

will be able to colonize from nearby sources.

- The disturbed site will

preserve natural interactions between individual plants growing on

the site and adjacent to the site, including their genetic integrity.

- No exotic

plant species that could impede revegetation are on the disturbed site

or nearby.

- The

site is more than 160 feet (about 50 meters) from a trail, destination

area, or campsite.

- Recreation use can be controlled to manage site recovery.

- The

site's appearance is not a factor.

- The site has topsoil, natural

levels of soil compaction, and soil microbes are still intact.

- The site

is stable (no active human-caused soil erosion).

- No other factors are known that might impede natural recovery.

Passive restoration requires managers to accept whatever time scale Mother Nature dictates. For example, the lush forests of the Eastern United States seem to recover rapidly without human intervention. In contrast, most upland Western ecosystems require decades, if not centuries or millennia, to recover. A long timeframe for recovery may be acceptable—give yourself permission to think beyond human time scales. Such long time scales may not be acceptable if resource values would continue to degrade or if social setting objectives cannot be met. Appendix D, Case Studies, includes an excellent case study that describes how implemention of a grazing system allowed a meadow on the Dixie National Forest in southern Utah to recover naturally.

At Rocky Mountain National Park, a lake shoreline (figure 2-16a) recovered naturally (figure 2-16b) after a dam was breached. The soil was rich with nutrients and still held a large seedbank and pieces of live plant material. The park was able to save the expense of a costly restoration project (Connor 2002).

Rocky Mountain National Park addresses passive restoration in the park's vegetation restoration management plan (U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service, Rocky Mountain National Park, 2006). A go/no-go checklist (U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service 2002) ensures that passive restoration is considered when criteria can be met. Otherwise, the checklist helps managers document the need for active restoration.

Figure 2-16a-A lakeshore in Rocky Mountain

National Park, CO, before recovery.

2.1.14 Active Restoration of Damaged Soil and Vegetation

Even with volunteer labor and partnerships, restoration projects in wilderness are expensive per square foot of area treated. In addition, restoration is a form of manipulation, although at a very small scale. For example, future researchers will want to know where your restoration sites are so they don't become confused while studying otherwise intact native plant communities.

Restoration becomes the "minimum tool" when less manipulative options would fail to return the area to an acceptable standard. If excessive impacts remain once other options have been implemented, restoration may be part of the solution.

2.1.15 Adjusting Management Actions: A Tale of Two Lake Basins

The examples of two different lake basins in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness in Washington show how management can be adjusted to bring areas toward their desired condition. The "minimum tool" strategy for each of these locations, developed through trial and error, involved a multipronged approach.

Lake Mary (figure 2-17), a subalpine lake basin, experienced many years of sheep grazing before it became a popular recreation destination. In the 1960s, managers installed picnic tables, a hitch rack, and garbage pits. In the 1980s, a number of management strategies were employed to reduce impacts. These included:

- Prohibiting

campfires

- Installing two toilets

- Moving the access trail to

a more durable alignment

- Restoring the area by transplanting plants salvaged during the trails project

Figure 2-17-Lake Mary, a popular recreation destination

in the Alpine Lakes

Wilderness, WA.

By then, the area had become wilderness, so all structures other than toilets were removed. Additional wilderness-wide regulations included a limit of 12 combined people and stock in a group, a 200-foot (about 61-meter) setback for stock access, and a regulation making it illegal to enter a closed restoration site.

These strategies were working in part, but the impacted areas, including the areas that had received restoration treatments, were not improving (figure 2-18), according to monitoring data. Factors that prevented the impacted areas from improving included continued erosion and compaction, continued human and stock use in closed sites, and the loss of the organic soil horizons. In 1992, a site assessment was completed. The following year, additional strategies were adopted. They included:

- 200-foot (about 61-meter) stock

setback

- Campsite designations to concentrate use

- Delineation of trails and campsites with barriers such as logs or rocks

Figure 2-18— The worst eyesore at Lake Mary was a large,

denuded

stock camp near the lake's outlet. Despite previous

restoration

attempts,

continued

use of the site deterred

recovery.

(This view of the camp was created by splicing

two photos.)

The restoration work was redone with a much more intensive approach—steep sites were stabilized with checkdams before being backfilled with mineral soil and topsoil carefully gleaned from sources nearby. High school students grew plants from locally collected seed. In addition, the sites were seeded when the seedlings were transplanted. A better erosion-control product was used and oak signs were installed to close restoration sites permanently. At first, a small map was installed to help users locate campsites, because only two sites were visible from the lakeshore.

Fast forward from 1993 to 2002. The revised management strategy is meeting with success. The restoration work is flourishing in most locations. Visitors know where they can walk and camp. The foreground view by the lake is dominated by native vegetation and well-located trails (figure 2-19), instead of a huge, bare-dirt campsite that blocked access to the lake. Visitors say that Lake Mary looks far better now than it did in previous decades.

Figure 2-19—Two volunteers and a paid crewleader spent 33

workdays

installing barriers and adding locally collected topsoil

to this former stock

camp at Lake Mary. Native greenhouse-grown

seedlings were planted, and locally

collected seed was sown across

the

site.

Four years later, most plantings were

thriving and seeded

species,

such as Sitka valerian, were becoming established.

Barrier logs

defining the trail remained in place. Silt no longer flowed directly

into

the lake, and a more attractive view greeted visitors to Lake Mary.

Now let's contrast the experience at Lake Mary with the experience at the popular Enchantment Lakes Basin. In comparison to the annual precipitation of 81 to 100 inches (2.06 to 2.54 meters) at Lake Mary, the Enchantments receive about 46 to 60 inches (1.17 to 1.53 meters) of precipitation, mostly as snow in winter. Climbing into the Enchantments requires a very steep scramble. As a result, the area has never had stock use or commercial grazing. The area became popular in the 1960s and 70s when hundreds of people camped in the 3-square-mile (7.8-square-kilometer) basin on weekends. Campsites formed on virtually every flat, dry spot. Hundreds of campsite inventories document extensive impacts during that era.

By the early 1980s, the vegetative condition had declined to a range rating of "poor" because of human foot traffic alone, despite many aggressive management strategies. Campfires had been prohibited, toilets had been installed, trails had been hardened, and group size had been limited. Local soils are so thin and dry that attempts at restoration succeeded only in the wettest of locations (figure 2-20). Because the lakes had measurable levels of fecal coliform and fecal streptococcus from human and dog feces, vault toilets were installed and dogs were prohibited.

Figure 2-20—Thin, dry soils in the Enchantment Lakes Basin have

scuttled most restoration efforts. (This photograph was digitally

altered to

remove distracting elements.)

In 1987, a limited entry permit system was implemented to manage a carrying capacity of no more than 60 people overnight at one time. A few years later, the group size was reduced to eight. Education messages (figure 2-21a) were strengthened to coach people on how to walk, camp, and even urinate (the mountain goats paw up vegetation to eat the salt in urine) in a way that protects fragile meadows.

Figure 2-21a—Coauthor Chris Ryan (left) checks a climber's

limited entry permit and explains policies designed to reduce

visitor impacts

at the fragile Enchantment Lakes Basin.

Long-time visitors are beginning to notice an improvement in vegetative condition, which can be attributed to many factors. Trail hardening (figure 2-21b) and cairns marking the trails keep most traffic on a durable route, preventing hikers from creating parallel trails and damaging sensitive shorelines. Well-established campsites can accommodate the reduced use. Prohibiting campfires and providing toilets (figure 2-21c) further limited the development of social trails. This area will always pose management challenges, but the overall trend of wilderness quality is no longer declining. Because of the area's harsh conditions, management actions other than restoration proved more effective in reaching objectives.

Figures 2-21b and 21c—The combination of reducing use,

hardening

trails (top), installing toilets (bottom), and

prohibiting

fires

has been a

more successful

strategy than

restoration for reducing impacts at the Enchantment Lakes Basin.