Gros Ventre Slide

The Gros Ventre Slide Geological Area was designated by the Forest Service in 1962 to preserve and commemorate the 1925 Gros Ventre landslide. It serves as a reminder that geology is always changing, sometimes slowly, and sometimes in the blink of an eye.

Hike through history

To honor the 100th anniversary of the Gros Ventre Slide, Kelly Elementary School students spent a year learning about geology and the slide. Their efforts produced a brochure to enhance learning for all who visit the Gros Ventre Slide Geological Area. Download the self-guided interpretive trail brochure, explore the geology of this unique area, and learn about the plants and animals that have adapted to live in a changed environment.

When the Mountain Moved

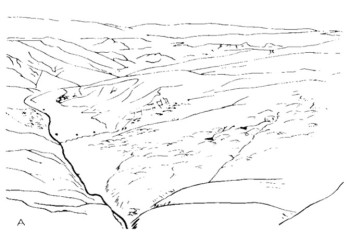

Aerial view of the Gros Ventre landslide in 1955

(WB and JM Hill)The Gros Ventre landslide is located in the Gros Ventre Mountains, east of the Tetons. It was caused by a complex combination of underlying geology, a thick snowpack, heavy rainfall, and the river below, which undercut the Tensleep Sandstone.

The landslide had shown ominous signs of instability on the morning of June 23, 1925, showing cracks and water seeping from the bottom of the slide. That changed by 4 p.m. that afternoon when the landslide sent 50 million cubic yards of the north face of Sheep Mountain catapulting towards the valley floor.

A River Dammed

The landslide formed a natural earthen dam that blocked the flow of the Gros Ventre River. With nowhere to go, the water quickly started rising. Eventually, the free-flowing Gros Ventre River transformed into Lower Slide Lake. This was not the first time a landslide had blocked the Gros Ventre River. A landslide, likely thousands of years old, dammed the Gros Ventre River upstream to form Upper Slide Lake.

There are several eye-witness accounts of the landslide and the rapid rise of Lower Slide Lake on June 25, 1925. The witnesses were homesteaders, ranchers, and Forest Service rangers in the Gros Ventre valley. The experience of the slide differed greatly depending on where the observer was in the valley. To some it was a violent surge of rock, trees, and wind. Others hardly took notice.

Likely Stages of the Gros Ventre Landslide

There are no direct observations of how the landslide developed, but geologists have created a scenario how the events unfolded based on the evidence left behind. Below are the stages that the Gros Ventre landslide likely went through. Click on the images to learn more.

Eyewitness Accounts

The Gros Ventre landslide in 1925.

(WC Alden)Guil Huff

On the afternoon of June 23, 1925, Guil Huff, a local landowner, was riding his horse along the Gros Ventre River when he heard loud rumblings. He looked to the south and witnessed a massive landslide descending rapidly towards him. He and his horse escaped the impact of flying rocks and debris by a mere 20 feet. In a matter of minutes, the landslide covered 17 acres of his ranch. It is estimated that 50 million cubic yards of rock collapsed, sliding at about 50 miles per hour and riding 300 feet up the opposite slope. The landslide blocked the Gros Ventre River, creating an earthen dam. With the valley blocked by the landslide dam, the Gros Ventre River had nowhere to go, and the Lower Slide Lake level continued to rise. By June 29, the Huff house was floating in the lake, to be joined by the Forest Service ranger station on July 3.

“During the morning, I was ploughing in my field about one-half mile above the center of the slide area. I noted cracks at the base of the hill and seepage was also showing along the base of the hill and the sloughing and seepage continued to occur along a section about a half mile… At four o'clock I rode horseback down to the slide looking for cattle and, attracted by the movement of the hill, was interested in seeing what was taking place. All of a sudden, a cut bank rising about 30 or 40 feet high at the south side of the river started to roll into the stream; then with a rush and a roar came the entire side of the mountain, spreading out in a fan shape and rolling forward with great speed. I turned my horse and rode with all possible speed up the river, needing to change my course twice in order to keep away from the on-rushing mass of rock, trees, and earth. It reminded me of a flood of water and only the good horse upon which I was mounted prevented me from being buried. The whole thing was over in about a minute and a half.”

Seaton, Cole, and Boyd Charter

Bob Seaton, Forney Cole, and Boyd Charter were cowboys driving cattle to their summer range to the east during the slide. The Jackson Hole Courier reported that the cowboys, “likened the action to a wave of water as it rushed down the mountain.” Cole had just cut a cow with his horse when he saw a force of air blasted a bridge upstream right in front of him.

Ned Budge

Ned Budge, searching for horses on Windy Point, northwest of the slide, witnessed dust rising as the slide began to move. He could hear a loud hissing sound at first, then a big rumble that grew to a roar.

Violet Huff

Violet Huff, Guil Huff’s wife, also reported seeing a portion of the moving slide mass from a west-facing window of her house while she was sewing but did not think much of it. She heard a muffled “shifting” sound and continued at her work. She was amazed a few minutes later when her husband returned to the house to discover what happened.

William Card

William Card was ploughing his field during the slide and remarkably kept on plough through the event.

The Kelly Flood

After the lake level stabilized, locals questioned whether the natural earthen dam was stable enough to hold back the waters of Lower Slide Lake. Engineers and geologists came to study the slide and dam, determining that the dam was stable and safe. Spring runoff in 1926 passed with no issues. However, the winter of 1927 was snowy and the lake levels rose rapidly after a surge of spring melt and rain. The lake overtopped the earthen dam and eventually gave way. A wall of water, mud, rock, and trees flowed down the Gros Ventre River, destroying ranch lands. The small town of Kelly, 3.5 miles downstream, was nearly obliterated on May 18, 1927. Six people and hundreds of domestic livestock perished.

More to the Story

William "Uncle Billy" and his cabin in the Gros Ventre valley in 1918. The cabin was buried in slide debris in 1925.

William Bierer, a gold prospector in the area, predicted that the north slope of Sheep Mountain would fail catastrophically. Convinced by his theory, Bierer sold his ranch to Guil Huff, an unsuspecting cattle rancher in 1920. Bierer died in 1923 before his observations and predictions became reality.

The Gros Ventre Mountains are made up of tilted and folded sedimentary layers draped over a granitic core. Only the sedimentary rocks are exposed around the Gros Ventre landslide. The crystalline granitic rocks of the Gros Ventre can be seen deep in the range on high peaks. The mountain range formed due to compressive forces from the southwest and northeast during the Laramide mountain building event, about 60-70 million years ago. The tectonic forces folded and faulted the rocks, resulting in the complex geology of the Gros Ventre Range. This episode of mountain building occurred millions of years before the beginning of the Teton fault and the formation of the Teton Range and Jackson Hole valley.

Aftermath of the Gros Ventre Slide, 1925.

Landslides are a common occurrence in the Gros Ventre on a geological timescale. Landslides ranging from hundreds to thousands of years old are found throughout the Gros Ventre valley.

With each landslide comes a cycle of change. The Gros Ventre landslide moved rock and destroyed vegetation. Interestingly, some trees remained rooted in blocks of earth as they launched downhill and were able to survive in their new location after the slide. The altered landscape, with fresh soils, a newly-formed lake, and rocky ground, created different habitat for birds, fish, and mammals. Over time, the vegetation flourished, and different species transitioned with the changes. This cycle of destruction and renewal with each landslide will continue throughout the Gros Ventre valley as landslides continue to occur over the next thousands of years.

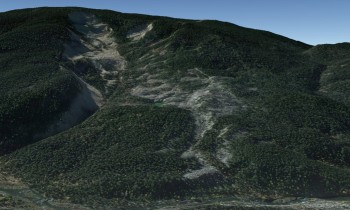

Google Earth imagery of the Gros Ventre landslide today

(Google Earth)Throughout the years, many people have wondered what caused this tremendous slide. Four primary factors are thought to have contributed to the event:

- Swampy ponds with no outlets within the slide area indicating poor water drainage within the slide.

- Heavy rains and rapidly melting snow saturated the rocks below, causing the Amsden Shale rock layer to become exceptionally slippery.

- The Gros Ventre River eroding through the overlying Tensleep Sandstone, produced a "free side" with no support holding it in place.

- Possibly an earthquake. There are reports of an earthquake in the Tetons leading up to the landslide. However, it is unknown if it would have been large enough to trigger the Gros Ventre landslide.

How does rain make rocks slippery?

Water increases what is called the "pore pressure" between sediment grains in a rock. The water pressure between the grains pushes the grains apart. The friction decreases and when the pressure is right, the rock fils and begins to slide.

Photographs from Eliot Blackwelder, a notable geologist, showing the slow movement of the Upper Gros Ventre landslide from his 1908-1911 in his 1912 report.

(Eliot Blackwelder)June 1925 was not the first time an active landslide was observed by settlers in the Gros Ventre valley. About 10 miles upstream of the Gros Ventre landslide is the "Upper Slide." In May 1908, the earth flow slowly crept downhill in blocks, forming cracks and upending trees. The Forest Service telephone line was continually in disrepair from the movement, as the poles crept downhill and snapped the wire. The Upper Slide has remained stable in recent years.

Photographed here is the Crystal Creek landslide, which slid in 2007, 2008, and 2010. The landslide dammed Crystal Creek forming Crystal Lake, similar to Lower Slide Lake. The freshly exposed rock of the Crystal Creek landslide makes it an obvious landmark. In contrast, the Gros Ventre landslide is slowly blending in as more vegetation inhabits the slide.

An example of a landslide geohazard that collapsed a section of Highway 22 along Teton Pass, severely damaging the road in June 2024.

A geohazard is a natural earth process, like an earthquake or landslide, that puts human health, safety, or property in harms way. The mountainous areas of western Wyoming are particularly susceptible to landslides, especially the Gros Ventre valley, Teton Pass, Snake River Canyon, and Togwotee Pass. Engineers work with geologists and road construction crews to monitor and mitigate against landslides that affect these major transportation corridors.

In 1959, tragedy struck campers on the Custer Gallatin National Forest in southwest Montana after a 7.2 magnitude earthquake struck in the middle of the night. The earthquake triggered a large landslide that blocked the Madison River forming Quake Lake. There were 28 fatalities.

The Army Corps of Engineers decided to cut a channel into the Madison Canyon landslide dam to lower the lake level. Their decision to create a spillway was influenced by the failure of the Gros Ventre Lower Slide Lake dam.