Construction Tools

- Measuring Tapes

- Framing Squares

- Plumb Bob

- Levels

- Surveyor's Transits and Electronic Instruments

- Saws

- Axes

- Adzes

- Planes

- Draw Knives

- Bark Spuds

- Tools for Drilling Holes in Wood

- Clamps

- Wrenches

- Chisels

- Mallets

- Hammers

- Crowbars

- Tools for Digging Holes

- Wheelbarrows

- Compactors

The standard tools used for trail construction are also needed for building a trail in a wetland. Standard trail tools are not described here. Instead, this report focuses on tools specifically needed for wetland trail construction. Find out more about handtools in MTDC's Handtools for Trail Work report (Hallman 2005) and two-part video (98-04-MTDC).

Measuring Tapes

Measuring tapes are a necessity for estimating and constructing a wetland trail. Construction measurements for wetland trails are often taken from the trail centerline. It is frequently necessary to divide by two. Metric measurements offer an advantage over English measurements in such cases. In addition, there is a move from the English system of measurement to the metric system (appendix F). Buy new tapes that are graduated in both systems.

Tapes 50 feet and longer are made of fiberglass, cloth, or steel. Fiberglass is best for the wet, brushy environment of wetlands. Cloth is not recommended because it will wear and rip easily. Long steel tapes may rust, kink, and break when used in wetlands. Short steel tapes, 6 to 30 feet long, are essential.

The longer tapes are best for estimating quantities of materials and hours needed for construction and for laying out centerlines of sleepers, bents, and other structures. The shorter steel tapes are handy for the actual construction.

Framing Squares

Framing squares (figure 73) are thin, L-shaped pieces of steel with a 90-degree angle at the corner. Each leg of the L is 1 to 2 inches wide and graduated in inches (or centimeters) from both the inside and outside corners of the L. The legs may be 8 inches to 2 feet long. Framing squares are used to mark hole centers and timbers to be cut at a 90-degree angle and to provide a straight, firm edge for marking angled cuts.

Plumb Bob

A plumb bob is a solid steel or brass cone, 3 inches long by 1½ inches in diameter. The plumb bob accurately transfers measured points above the ground to comparable points on the ground. It is useful for locating the centers of holes to be dug.

Levels

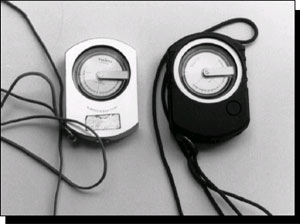

Specialized levels are useful for wetland trail work. An Abney hand level or a clinometer is accurate enough to be used for setting grades during the preliminary layout of most wetland trails (figure 74). String or line levels and carpenter's and mason's levels are needed during construction.

Figure 74—Use a clinometer to set grades

for preliminary trail layout.

String or Line Levels

There are two types of string or line levels: one establishes percent of grade easily, the other does not. Each level is about 3 inches long by ½ inch in diameter and has a hook at each end to hang the level on a string. The string is pulled tight between two points in an almost horizontal line. One of the points must be at a known elevation. The string level will be used to establish the elevation of the other point.

The most common type of string level has two marks on the level tube. These marks are equidistant from the high point of the level tube. Center the level bubble between the two marks on the tube by raising or lowering the string at the second point. When the bubble is centered, the string is level. If the tread is to be level, this is the elevation to be met. If the tread is to be sloped, the difference between the two points must be calculated; the elevation to be met is established by measuring the difference needed, up or down, from the level line.

In the second type of string level, the high point of the level bubble is off center. The level tube has five graduations. The first two are widely spaced. The rest are closer together, but evenly spaced. When the bubble is centered between the two widely spaced marks, the string is level. When the edge of the bubble touches the third mark, the string is at a 1-percent grade, the fourth mark is at a 2-percent grade, and so forth. A string level is accurate enough to begin to establish relative elevations and slopes for small wetland trail projects (figure 75).

Figure 75—String levels and a chalkline.

Stringlines

Almost any type of string can be used for a stringline, but for repeated use a professional stringline is best. This type of stringline is a tightly braided string wound around a short, narrow piece of wood, plastic, or metal. Usually there is a metal clip, or a loop, tied on the end.

The stringline extends a straight line to reference the location of the next section of construction. The stringline can also be used with string levels to establish relative elevations and slopes.

Chalklines

A chalkline is another type of stringline used to mark a straight line between two points on a flat surface. The marked line is commonly a guide for sawing.

Professional chalklines come in a metal case that holds the coil of string and the chalk dust. One end of the chalkline is held tightly at a fixed point on the surface of the object to be marked. The chalkline is stretched to the mark at the opposite end and held tightly at that point. Hold the chalkline at about midpoint, pull the chalkline straight up from the surface and release it. The chalkline will snap back into place, leaving a sharp, straight line of chalk between the two points.

A chalkline is useful for marking the centers of sleepers and bents for a deck that needs to be in a straight line, or the edges of a deck to be trimmed uniformly, or the edges of a log to be cut with a flat face.

Carpenter's and Mason's Levels

There used to be a distinction between carpenter's levels and mason's levels. Carpenter's levels were wood or wood with steel strips to protect the edges. The mason's level was all or mostly steel. Today, wood, steel, aluminum, and plastic are used in either type of level.

These levels are available in lengths of from 2 to 6 feet. Given the abuse trail tools take, steel or aluminum levels are best. A 3- to 4-foot-long level is more accurate than a shorter level. These levels are easier to pack than 5- to 6-foot-long levels. Plastic levels are also available and cost less.

The levels have three tubes mounted in the body of the level. One level tube is parallel with the length of the level, one is perpendicular to it, and one is at 45 degrees to the other two. When a level bubble is centered, the edge of the level is either level, vertical, or at 45 degrees.

Torpedo Levels

A torpedo level is steel or aluminum and plastic and only 8 to 12 inches long and 1 to 2 inches wide. It is used to determine if a surface within a confined area is level, for example the surface of a notch. Although the torpedo level is not as accurate as the longer levels, it can be used to check whether an item is out of level, or out of plumb. If so, a more accurate level can be used to make the corrections.

Post Levels

Post levels save time when setting posts and piles. They are basically plastic right angles that are 4 inches long in three dimensions. Two level tubes are mounted in the two faces of the level. Set the level along the side of the post or pile, and use a crowbar or shovel to adjust the post or pile until it is plumb (figure 76).

Surveyor's Transits and Electronic Instruments

Hand-held tapes and levels are adequate for short destination or loop trails in a wetland, or for low, poorly drained sections of existing trails. However, for trails longer than a quarter mile or over undulating terrain, more precise measurements might avoid future problems. Control points for elevation and slope can be established using surveyor's transits or a variety of electronic instruments.

Surveyor's Levels or Transits

Old surveyor's levels or transits may be hiding in a closet or storage area at some agency offices. Blow the dust off and try to find someone who knows how to run the instrument. A builder's level or transit may be less accurate, but should work. A surveyor's level rod will be needed to obtain distances and elevations. Distances can be quickly measured optically using stadia.

Electronic Distance Measuring Instruments

Two types of electronic distance-measuring instruments (EDMs) are available. The least expensive type is hand held and can measure distances across a flat surface to a point from 2 to 250 feet away. This type of instrument does not provide elevations of points or information needed to determine slopes and relative elevations. It will not provide accurate distance measurements if vegetation impedes the line of sight.

More expensive instruments can measure distances up to 12,000 feet with an accuracy of 0.02 to 0.03 feet. A direct, clear line of sight is required.

Global positioning systems (GPS) provide horizontal positioning through the use of coordinates and can provide elevations. This equipment may cost from a hundred dollars to several thousand dollars depending on the quality. The skills needed to operate GPS equipment vary depending on the equipment's sophistication and accuracy.

The accuracy of small hand-held instruments can be close to 1 meter (3.28 feet), in open, relatively level terrain, sufficient accuracy for trail work if frequent points are taken along the route.

Survey-grade GPS instruments also are available for more precise work. These instruments require extensive training and experience in their use. They are also very expensive.

GPS technology changes quickly. Technological advances, reduced costs, and increased accuracy have resulted in many practical and affordable GPS trails applications.

Saws

Handsaws

Most timbers and logs used in wetland trail construction are of relatively small diameter. Usually the largest are the piles, 6 to 10 inches in diameter.

If only a few pieces must be cut, or if wilderness regulations require, a one-person crosscut saw can do the job. This is an old-fashioned large handsaw. The blade is 3 to 4 feet long and heavier than a carpenter's handsaw, with much larger teeth (figure 77).

Chain Saws

If many pieces of wood need to be cut, and if regulations permit them, chain saws do faster work for cutting the small sleepers, piles, and planks used for some wetland trails. A small, lightweight saw designed for tree pruning is better for cutting horizontally on vertical piles, posts, and other items. Pruning saws are available weighing 8 pounds, with a 12- to 14-inch bar.

The sawyer should be adequately trained and experienced in the use of the chain saw and the safety equipment. Most government agencies, the Forest Service included, require workers to receive special training and certification before they are allowed to use a chain saw.

Figure 77—A one-person crosscut saw is a

good choice for backcountry

settings.

Hand-Held Pruning Saws

Small hand-held pruning saws are used on most projects. Most types have a curved blade 12 to 26 inches long. For wetland work, the shorter saws are adequate. Some saws have a wood or plastic handle that the blade folds into when it is not being used. Small pruning saws with a straight blade 6 to 8 inches long are available. The short saws with the straight blade work well for cutting shallow notches in log sleepers. When the saws are folded, they can be carried in a pocket (figure 78).

Axes

Three kinds of axes are commonly used in trail work: singlebit, double-bit, and broad axes. The hatchet is not included in this tool list. A Maine guide once wrote that the hatchet is the most dangerous tool in the woods. He may have been right. It takes only one hand to use a hatchet. The other hand is often used to hold the piece of wood to be cut—not the safest thing to do. Few trail crews include a hatchet in their toolbox.

Proper ax selection, care, and use is described in MTDC's videos and reports: An Ax to Grind: A Practical Ax Manual (Weisgerber and Vachowski 1999) and Handtools for Trail Work (Hallman 2005).

Adzes

If the hatchet is the most dangerous handtool in the woods, the carpenter's adz is the second most dangerous. A person getting hurt with a hatchet has usually been careless. It is not necessary to be careless to get hurt using an adz. The carpenter's adz is used for cutting a level surface on a log for some types of puncheon and gadbury and for removing knots and bulges on log surfaces.

The blade of a carpenter's adz is 5 inches wide and similar to an ax except that it is mounted perpendicular to the line of the handle, similar to a hoe. The edge must be sharp. The handle is curved, similar to a fawn's-foot handle on a single-bit ax.

Workers using an adz normally stand on a wide log (16 inches or more in diameter) and swing the adz toward their feet, almost like hoeing a garden. An adz can be used on smaller-diameter logs by a worker standing next to the log and chopping sideways along the length of the log. When one face of the log is cut to a level plane, the log can be turned and another face can be cut. It is extremely difficult to use a long-handled adz to cut anything but the upper surface of a log.

Two other types of carpenter's adzes have short handles. They are not suitable for shaping large logs, but work well for removing knots and bulges and for cutting notches. Short-handled adzes are made with a straight or concave blade, about 3 inches wide. Striking the back of the adz head with a hammer will eventually crack the head (figure 79).

Planes

Small block planes can be used for shaping bevels and chamfers, for removing unevenness where two pieces of wood butt together, and for smoothing splintery edges that visitors might touch. Block planes are small, about 2 inches wide and 4 inches long, and easily packed to the worksite (figure 80).

Figure 80—A small block plane is useful for

finish work on wood

structures.

Draw Knives

Draw knives are often used to peel the bark off logs. Logs will last longer without the bark. Draw knives work best on logs with thin bark.

Draw knives have either straight or concave steel blades that are 12 to 15 inches long with a wooden handle at each end. The draw knife is pulled toward the worker. The straight draw knife does not put as much of the edge against the wood as the concave knife, making the concave knife more efficient and more popular (figure 81).

Figure 81—Straight and concave draw knives.

Bark Spuds

Bark spuds are better suited for removing the bark from thickbarked or deeply furrowed logs and logs with many knots or large knots. Normally, logs are most easily peeled when the tree is still green, but this characteristic varies by tree species. Bark spuds are from 18 inches to 6 feet long. All have a steel head that is 2 to 3 inches wide and 3 to 5 inches long, sharpened on the end and both sides. The wooden handle is 15 inches to 5½ feet long (figure 82).

Figure 82—A bark spud works well

when peeling green logs.

Tools For Drilling Holes in Wood

Bits

Bits are used to drill holes in wood for bolts and for pilot holes for nails and screws. Some of the types of bits available are twist bits, chisel bits, augers, and ship augers.

Twist bits are intended for use on steel, but the smaller bits can be used for drilling pilot holes in wood for nails and screws (see appendix D for appropriate pilot hole sizes). Chisel bits resemble a chisel with a point in the center. Chisel bits tend to tear up the wood around the hole on the top and bottom surfaces of the wood, but they are readily available in diameters of 1/16-inch increments. Augers resemble a widely threaded screw with a sharp end and sharp edges. Augers do not tear up the wood like chisel bits do. A normal auger bit is 6 inches long and readily available in ¼- to 1½-inch diameters, in 1/8-inch increments, less readily in 1/16-inch increments. With a 6-inch-long auger, it is difficult to get the holes to line up when two 3-inch ledgers are on each side of a 6 by 6 pile. Ship augers help in this situation because they are longer. Ship augers are 15, 17, 18, 23, and 29 inches long and are indispensable when working with timbers and logs.

Old auger bits were made with a four-sided shaft to fit into a manually powered brace or drill. A six-sided shaft is designed for use in a power drill and will spin uselessly when used in a manually powered brace or drill. Today, most bits are made for power drills. When selecting a bit from a maintenance shop, check to see that the shaft of the bit matches the brace or drill to be used at the worksite (figure 83).

Figure 83—Ship augers are longer

than normal 6-inch augers.

Braces

Braces and bits are the traditional tools for drilling holes in wood. The brace, a handtool suitable for wilderness use, is extremely slow. Old braces require an auger bit with a foursided shaft (figure 84).

Figure 84—A traditional brace and bit.

Some braces are made with a ratchet, which is helpful when working in close situations where the brace cannot be turned a full circle. People have a tendency to lean on the brace to speed up drilling. This practice bends inexpensive braces. Buy a good brace or don't lean on it. Keep the bits sharp.

Battery-Powered Drills

Small battery-powered drills are useful for drilling holes 1/16 inch to 3/8 inch in diameter. Some heavy-duty drills can drill holes up to 1 inch in diameter. Battery-powered drills may be practical for backcountry use where only a few holes are to be drilled, where the crew returns to the shop after work, or where a generator or photovoltaic power source is available.

Gasoline-Powered Drills

Many trail crews use gasoline-powered drills. These tools can drill holes up to 1 inch in diameter and weigh from 10 to 12 pounds, plus fuel (figure 85).

Figure 85—Gasoline-powered drills are great for

backcountry work if

regulations allow their use.

Only the more expensive heavy-duty drills, whether battery or gasoline powered, have a reverse gear. A bit can become stuck if it does not go all the way through the wood. To avoid getting a bit stuck, lift the drill up a few times while drilling each hole. If the bit does get stuck, disconnect the bit from the brace or drill and use a wrench to twist the bit backward.

If you have a generator at the worksite, another alternative is to use a ½-inch-diameter electric drill. Most of these drills have a reverse. An annoying drawback is stepping over a long extension cord and getting it tangled in brush and timbers. If the operator is standing in water, electric shock is a possibility. Generators are heavy and require fuel. Although some generators have wheels, most are awkward to transport to wetland sites.

Clamps

A pair of large jaw clamps can speed the installation of two ledger bents. The clamps should have at least a 12-inch opening. These clamps are used for making furniture and may be all steel or part steel and part plastic. Both ledgers are placed roughly in position and clamped loosely to each pile. The height of each ledger is adjusted, the clamps are tightened, and the bolt holes are drilled (figure 86).

Wrenches

At least one wrench is needed to securely fasten carriage bolts and lag screws. Two wrenches are needed to fasten machine bolts and all-thread rod. Specialty wrenches or screwdrivers are needed to install vandal-proof screws. Closed-end and open-end wrenches, and a set of socket wrenches, may all be needed. Tying one end of a cord to the wrench and the other end to your belt may help keep the wrench from getting lost in the water or mud.

Chisels

Wood chisels are needed for wetland trail structures. The blade may be ¼ to 2½ inches wide. Wood chisels are typically made with short handles, which often contribute to scraped knuckles. It is worthwhile to repair or replace the handles of old, long-handled chisels.

For a small amount of close work, the wood chisel can be hit or pushed with the palm of the hand. If this technique is impractical, use a wooden mallet. Hitting a wood chisel with a steel hammer will damage the chisel's handle. A good wood chisel should not be used close to nails, screws, or bolts. The cutting edge should be kept sharp.

The socket slick, an oversized chisel, is a difficult tool to find. However, if considerable notching or other accurate work is required, obtaining a slick will be worth the extra effort and expense. The blade is 33/8 inches wide with an 18-inch wooden handle. The slick weighs 3 pounds. A 2-inch-wide chisel weighs just 10 ounces. The advantages of the slick are its wide blade and long handle. The slick can remove wood twice as quickly as a wide chisel. The long handle keeps the hands farther from the wood being cut (figure 87).

Figure 87—Socket slicks can be hard to find.

Mallets

Mallets are made with plastic, wooden, leather, or rubber heads. Mallets with plastic or wooden heads should be used for hitting wood chisels.

Hammers

Claw Hammers

A carpenter's claw hammer is helpful for nailing log culverts, bog bridges, boardwalks, and geotextile fabric. A 28-ounce framing hammer is better than the lighter models, although the heavy hammer may be awkward for workers who are unaccustomed to it.

Sledge Hammers

A variety of different weight sledge hammers should be available at the worksite. A 4-pound sledge is good for starting driftpins and spikes. A 6- or 8-pound hammer is better for driving them. The 8-pound hammer is better suited for moving heavy timbers and logs fractions of an inch when they are almost in place. Surveyor's sledge hammers have shorter handles. They are better for driving long pieces of steel because they provide better control.

Crowbars

A crowbar is indispensable for building trails in rocky terrain. For most wetland trail work, the crowbar is used to move fallen trees and logs out of the way and to align piles, logs, and timbers. A crowbar, also called a rock bar or pry bar, is much stronger than a hollow-pipe tamping bar. The two are often confused.

Tools for Digging Holes

Shovels and Posthole Diggers

The sharp-pointed shovel can be used for digging a narrow deep hole, but a posthole digger or manual auger is more efficient. The posthole digger with its clamshell-like blades is most common, but it is slow and awkward to use. The auger is more expensive, but more efficient.

Augers

The auger blade consists of two pieces of immovable curved steel set at opposing angles to each other. The wooden handle is turned in a horizontal plane while the blades drill a hole in the ground. In most soils an auger is more efficient than a posthole digger (figure 88).

Gasoline-Powered Augers

Gasoline-powered augers are available. These can usually be rented from local equipment rental companies. A one-person auger weighs 18 to 140 pounds. A two-person auger weighs 35 to 75 pounds. These augers are easily moved to a site. The heavier one-person augers have an engine mounted on wheels that is separate from the auger. Power augers usually make fast work of drilling holes in almost any soil. Problems occur when the auger runs into a boulder, a large root, or soil containing 4- to 6-inch pieces of gravel. The bit will stop, and the torque of the engine may cause back injury.

Wheelbarrows

Wheelbarrows are an underrated and often forgotten piece of equipment for trail work. A wheelbarrow is a necessity for moving fill for most turnpike construction and can be helpful for moving tools, materials, and supplies. For big jobs, two wheelbarrows are handy. One can be loaded while the other is being dumped.

Steel and fiberglass are the most common materials for the body. Steel is heavier and stronger, but fiberglass is cheaper and more easily repaired.

Wheelbarrows commonly available at most local building supply stores do not withstand the rigors of trail work. Contractor's wheelbarrows are made with stronger steel, and the handles are made of heavier, better quality wood. Although more expensive, a contractor's wheelbarrow will far outlast the flimsy backyard variety. Contractor's wheelbarrows can also be rented.

The solid-body wheelbarrow is the type that comes to mind when we think of wheelbarrows, but the gardener's wheelbarrow also has a place in trail construction. This wheelbarrow, without sides, is easier to use when loading large stones, short timbers and logs, and bags and boxes of materials. Gardener's wheelbarrows are more expensive than contractor's wheelbarrows and are difficult to find. Most have steel wheels. Pneumatic rubber tires are better for trail work. The frame of a standard wheelbarrow can easily be converted to a gardener's wheelbarrow. Temporary flat-tire repair sealants, sold in aerosol cans, help prevent pneumatic tires from going flat. Motorized carriers could greatly ease the burden of moving materials, where their use is allowed.

Compactors

Compactors should be used when placing fill for turnpike and for backfill around end-bearing piles. Several companies make a vibratory tamper type of compactor that is suitable for compacting small areas of fill. These companies also make vibratory plates, which are better suited for larger areas, such as turnpike and accessible surfaces. Vibratory tampers have an area 8 inches square that contacts the ground. Vibratory plates have an area 15 inches square that contacts the ground (figures 89 and 90).

A third type of compactor is an attachment to the Pionjar rock drill. It can be used for compacting backfill in narrow spaces around end-bearing piles, fenceposts, and signposts.