Chapter 10—Securing Horses and Mules

After riders unload their stock at a recreation site, keeping them there can be a challenge. Stock may escape when a handler accidentally leaves a corral gate open, when a mule opens a gate or unties itself, or when a rider falls off and the horse runs away. A combination of continuous perimeter fences, road barriers, and trail barriers is vital. Inside the recreation site additional confinement methods are used. Corrals and highlines secure stock at camp units, especially overnight. Hitch rails serve short-term needs. Arenas and round pens provide space for exercising and training horses and mules.

Importance of Perimeter Fences

When a horse or mule gets loose, it may remain calm or it may run wildly about. Other stock nearby may get nervous if they see or hear a loose animal running because they assume it is running from a predator. Powerful instincts kick in, and the stock nearby may try to join the freed animal and flee the perceived threat. An unbroken barrier around the recreation site makes it easier to catch escaped stock and prevents them from running headlong onto a busy road. Perimeter fences also keep large wildlife or domestic animals, such as cattle, out of the site. These uninvited animals are nuisances and can hurt recreationists. Combine perimeter fences with a barrier at the site entrance.

If the terrain is varied, locate perimeter fences on the highest point of the landscape. Horses and mules watch the horizon and are more likely to see the fences there. They may not notice fences in drainages or hollows.

Fence Materials and Construction

The materials used to build perimeter fences and horse enclosures, such as corrals, arenas, and round pens, are often the same. Slight variations exist in construction details. For maximum security, perimeter fences should not be one side of a corral, arena, or round pen. When choosing materials for perimeter fences and horse enclosures, the primary consideration is safety. Materials must be durable, suitable for the application, and appropriate for the level of development. The goal is to choose horse-friendly, nontoxic materials that discourage chewing and scratching.

Horse Sense

Scratching an Itch

Horses and mules like to rub against fences, structures, and trees to relieve the discomfort caused by insect bites, dried sweat, or shedding hair. They can cause substantial damage when scratching their itch.

The cornerposts of perimeter fences need to be larger diameter than the lineposts, because cornerposts receive more stress. The recommended distance between perimeter fenceposts is 8 to 12 feet (2.4 to 3.6 meters). Set all posts in concrete and bury them an appropriate depth for local soil conditions. The higher the fence, the deeper the posts must be buried. Set cornerposts and gateposts deeper than lineposts. Regardless of the fence style selected, the bottom rail or strand should be no less than 1 foot (0.3 meter) from the ground, high enough to allow mowing or raking, yet low enough to prevent small stock from rolling under the fence. Corrals, arenas, and round pens should be 5 to 6 feet (1.5 to 1.8 meters) high. The recommended height for perimeter fences is between 4.5 and 5 feet (54 and 60 inches or 1,372 and 1,524 millimeters).

Avoid making square or rectangular enclosures that hold more than one animal, because they can be unsafe. Horses and mules that are being pursued are less likely to be trapped by more aggressive stock when enclosures are oval or have angled sections instead of 90-degree corners.

Post-and-Rail Construction

Post-and-rail construction is suitable for perimeter fences and horse enclosures. One style places the rails in line with the posts, and the other mounts the rails on the sides of posts. Of the two styles, inline construction generally is stronger, cleaner, and looks more professional (figure 10–1). Placing steel rails in line requires more welding and is more costly. Saddle-welded joints are preferred because they are stronger than surface- or butt-welded joints. Mounting steel rails on the sides of posts usually is more economical because it requires less labor. However, the fence appears bulky and may have weak joints at the cornerposts (figure 10–2). Rails on the inside don't pop off as easily if an animal runs into or pushes against them.

Some post-and-rail fences made of wood and vinyl have inline rails. The rails measure up to 16 feet (4.9 meters) long and are set in holes drilled through the posts (figure 10–3). Many traditional wood fences have rails attached securely to the sides of the posts on the inside of the horse enclosure.

Post-and-rail perimeter fences and horse enclosures may have three to five rails. Riders debate the required number of rails needed in corral fences. Some feel that the more rails in a corral fence, the better it is. They recommend using four or five rails, saying that the fence appears more solid to a horse or mule, reducing any temptation to run through it. Other riders say the more rails, the easier it is for an animal to trap a leg or hoof. These riders prefer three rails. When deciding how many rails are needed, seek input from riders who will use the enclosures. Regardless of the number of rails, fences must be free from sharp corners or protruding hardware. This is critical—horses, mules, and people get hurt when they rub against sharp objects.

Figure 10–1—Welded inline rails generally are stronger

than sidemounted

rails. Saddle-welded joints are preferred.

Figure 10–2— Steel fence rails mounted on the sides of posts are

more economical, but they may have weak corner joints.

Figure 10–3—Some rustic wood fences have inline

rails that pass

through holes in the posts.

Steel Post-and-Rail Fences

Fences made of steel posts and steel rails are suitable for most perimeter fences and horse enclosures. While steel post-and-rail fences cost more initially than fences made from other materials, steel fences are the most durable and will please riders. The horizontal rails usually are made from schedule 40 pipe that is at least 1 7⁄8 inches (about 47.6 millimeters) in diameter. Posts usually are schedule 40 pipe that is 2 3⁄8 inches (about 60.3 millimeters) in diameter.

Galvanized finishes reduce maintenance, but they may be too shiny for some settings. Black pipe is sometimes used because it rusts, allowing it to blend with less developed settings. However, rusted pipe tends to leave red particles behind when stock rub against it, something riders don't appreciate. If steel fences are painted, use an earth-toned enamel product that blends with the environment. Some stock chew on anything, including steel rails. If the steel rail is painted, chewing can make it unsightly.

Caps on posts keep rainwater from settling at the bottom and rusting through or weakening the posts. Caps on exposed pipe ends keep out bees and wasps.

Wood Post-and-Rail Fences

Wood post-and-rail fences blend well with the natural environment. However, most stock chew on wood fences (figure 10–4). Not only do chewed rails have to be replaced or maintained frequently, ingested wood slivers may be hazardous to stock. Wood rails can be treated with a solution that discourages chewing, but the solution is costly. Stock can easily damage wood fences or panels when they kick, especially if the rails are weak (figure 10–5). Wood post-and-rail fences need to be checked frequently for damage and decay.

Figure 10–4—Hungry or bored stock often chew on inappropriate

items, causing considerable damage.

Figure 10–5—Riders repair corrals with whatever materials are

available—in this case, baling twine and wire. Schedule regular

inspections and maintenance so riders don't have to make repairs

themselves.

Resource Roundup

Preserving Wood

For an overview of wood preservatives,

treatment processes, alternatives, and

guidelines, refer to Preservative-Treated Wood

and Alternative Products in the Forest Service (Groenier and Lebow 2006) at http://www.fs.fed.us/t-d/pubs/htmlpubs/htm06772809.

This site requires a username and password.

(Username: t-d, Password: t-d)

The American Youth Horse Council (1993) lists decay-resistant woods that are suitable for horse enclosures. Osage orange, western red cedar, western juniper, and black locust make good post materials without pressure treatments. Painting or staining wood fences may help them last longer. Waterborne treatments usually are safer for stock than oil-based treatments. Surface treatments require regular reapplication and are not as effective as pressure treatments. Although pressure-treated posts and rails last longer than untreated posts, avoid posts and rails treated with chromated copper arsenate (CCA), pentachlorophenol (penta), and creosote, because these substances may be harmful or toxic to stock.

Wood is most appropriate for perimeter fences, arenas, and round pens where horses and mules don't spend a lot of time. Stock spend more time in corrals and have more opportunity to chew or damage wood. Wood is still the most popular material for corrals in some areas of the country. Figure 10–6 shows a sturdy wood corral with round rails.

Figure 10–6—Sizable rails, attached to the inside of

posts, define

a classic wood corral.

Vinyl Post-and-Rail Fences

Molded vinyl materials (figure 10–7) are suitable for perimeter fences, arenas, and round pens because they are durable. Some synthetic fence materials that have a steel wire bonded inside are light, but are still strong enough for gates. When correctly installed, vinyl fences generally need little maintenance. Most synthetic materials have ultraviolet stabilizers and antifungicidal agents that aren't toxic to stock and stock don't find vinyl appealing to chew on. Vinyl has no sharp edges, so most stock don't get satisfaction from rubbing against it. Synthetic fence materials are available in many colors, including colors that harmonize with the surrounding environment—dark green, brown, and black. Vinyl and similar synthetic materials don't blend well in areas with a low level of development—they are more suited to highly developed areas. A disadvantage of vinyl fence panels is their high initial cost.

Figure 10–7—When they are installed correctly, vinyl post-and-rail

fences are strong, durable, require little maintenance, and

have no sharp edges to injure stock.

Premanufactured Tubular Panels

Equestrians commonly use premanufactured metal panels to construct horse enclosures at home. The lightweight, inexpensive panels are a popular substitute for steel pipe in corrals, arenas, and round pens. It is easy to construct temporary enclosures like the one shown in figure 10–8. An advantage of these panels is their somewhat forgiving nature. Horses and mules are less likely to be injured if they kick or collide with a panel than with a permanent fence.

Figure 10–8—Building a corral is quick and easy with

premanufactured metal panels.

The safest tubular fence panels are connected with hinged rods, but these panels are difficult to install on uneven terrain. Panels with loose pin connectors are easier to install on uneven surfaces, but stock may be able to catch a leg or tail in the gap between panels (see figure 10–62). Panels with rounded corners may appear safer for stock but they are actually more dangerous. If an animal rears higher than the rail, the rounded corner can funnel the animal's hoof or head into the gap between panels. A square corner with edges that have been ground smooth is better. Other fasteners include bolt clamps and rubber connectors to secure the panels solidly. Stock can rub on the protruding fasteners, which may give way, releasing the panel and freeing the horses.

If the recreation site budget does not cover steel pipe, vinyl, or wood for enclosures, consider using tubular fence panels—but use them with caution. Occasionally an agitated animal will knock the panels down and escape. Sometimes riders tie stock to panels when preparing for a ride. The unsecured panel may move if something spooks the tied animal and it pulls back. Frightened by the panel's unexpected movement, the animal may run off, dragging the panel behind it. There are several solutions:

- Install permanent posts in corrals, arenas, and round pens.

- Place hitch rails near horse areas, arenas, or round pens.

Wire Fences

A horse or mule is more likely to challenge materials it can lean over or push through. Because wire fence materials stretch, they are not suitable for corrals, arenas, round pens, or gates. Horses also can get their feet or heads caught in the wires. If they are constructed properly, wire fences may be used to secure a site perimeter. Smooth wire fences with four strands are generally adequate to discourage fleeing stock. Fences with five or six strands are even more secure.

A leaning or running animal can loosen wire fences—install materials on the inside of the posts for maximum strength. Avoid using T-posts for wire and wire-mesh fences, because stock may impale themselves on the posts. Pressure-treated wood is a sturdier—and safer—solution.

High-tensile, smooth wire of at least 12.5 gauge can be used instead of barbed wire. High-tensile wire coated with vinyl or plastic is safer—although it costs more than uncoated high-tensile wire. Coated, smooth wire costs less than post-and-rail construction and does not rust, stretch, or fade. When installed properly, coated wire provides an effective perimeter fence. Coated smooth wire is strong, somewhat flexible, and easier for stock to see than uncoated smooth wire. If stock do run into coated wire, they have less chance of injury than with barbed wire. When using smooth wire for a perimeter fence, consider adding a steel, wood, or vinyl top rail so that stock can see it easily. Using smooth wire instead of barbed wire doesn't eliminate the possibility that stock might get tangled in the strands.

Horse Sense

Barbed Response

In some areas, perimeter fences keep cattle out of the recreation site while keeping stock inside. The traditional cattle fence incorporates multiple strands of barbed wire, an unsafe practice for horse fences. When horses and mules catch a leg or hoof in fences, they often struggle vigorously to free themselves and sustain serious injuries. Barbed wire is generally not recommended for horse fences—many alternatives are safer. When barbed wire must be used, a compromise is to use smooth wire or wire mesh for the bottom of the fence, and a single strand of barbed wire at the top (figure 10–9). Do not use barbed wire for interior fences.

Figure 10–9—Barbed wire discourages cattle from leaning over

and breaking down a fence, but can be dangerous for horses and

mules. Choose an alternative fencing material in recreation sites.

Wire Mesh Fences

Wire mesh is made of woven wire or welded wire and is commonly used for horse fences. The bottom portion of the pasture fence in figure 10–9 is constructed of wire mesh. Woven wire is a better choice than welded wire, because aging welds can burst, resulting in sharp projecting ends. Although wire mesh is the least expensive fence material, it is not safe for use on horse corrals. When some horses and mules are kept in wire mesh enclosures, they try to climb or step on the wire grids. They can easily catch a hoof or horseshoe in the wire. Wire mesh is suitable for perimeter fences, arenas, and round pens because horses are not loose there for long.

Wire mesh stretches when a horse hits it, distributing the impact over a wide area and reducing injuries and damage. The mesh should be attached to a post-and-rail fence made of wood or steel (figure 10–10). As with all enclosures, secure the boards and wire to the inside of posts. For horse fences, V-mesh woven wire, a more costly variation, generally is safer than rectangular woven wire. Table 10–1 lists suggested materials for horse fences and gates. Table 10–2 compares characteristics of materials suitable for fences in equestrian recreation sites.

Figure 10–10—Attaching wire mesh to post-and-rail fences

makes the fence more resilient. Stock also can see it better.

Horse Sense

Electric Solutions

Many riders travel with portable electric corral kits that include posts, fasteners, stakes, a gate, synthetic wire, a tester, and a battery-operated fence charger. Horses and mules are very sensitive to small electrical shocks. One shock is usually enough to convince stock to stay away. When stock have been conditioned to electric fences, they generally don't test or challenge them, but if a horse or mule perceives a real or imagined predator, an electric fence will do little to deter the animal's flight. Animals, people, or property can be hurt. Other domesticated animals and wildlife may not respect electric fences, whether they are set up with single or double strands. This guidebook recommends using other fence options for equestrian recreation sites.

Cattle Guards, Gates, and Latches

Perimeter fencing by itself is not enough. To complete the continuous barrier around the recreation site, install gates at trail access points and roads. Within the recreation site, provide appropriate gates and latches for corrals, arenas, and round pens. Often a cattle guard is required by land management agencies, but most riders do not like them.

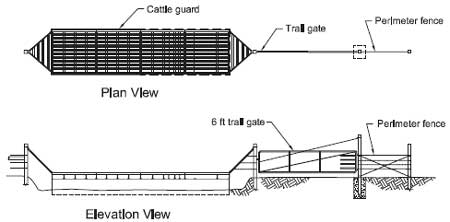

Cattle Guards

Many agencies require cattle guards on access roads to keep cattle out of recreation sites. Cattle guards are dangerous for horses and mules—whether they are loose or under saddle. They may try to walk or jump over the cattle guard or walk around its ends. They can trap a hoof or leg in the cattle guard, severely injuring themselves. Figure 10–11 shows a cattle guard that has objects and barbed wire in the angled side wings, creating hazards for all users. If a cattle guard is required, install a vehicle gate between the recreation site and the cattle guard to contain loose stock. If a gate is not feasible, consider painting bold, white parallel stripes on the pavement between the recreation site and the cattle guard. Some horses and mules are reluctant to cross these highly visible markings, and the sight may temporarily distract a fleeing animal. Cattle guards generally are subject to the MUTCD or the governing agency's sign requirements.

Figure 10–11—Some stock attempt to go around cattle guards.

Pieces of wood stuck in the wings of this cattle guard discourage

passage, but are safety hazards for all users. Find another

solution. Cattle guards must be marked according to the MUTCD

standards.

Road Gates

A gate provides a safe barrier that will be respected by loose stock. Provide gates at entrances to campgrounds and trailheads and at each loop road. Even though the loops may not be fenced, gates can help if access must be restricted for any reason, including maintenance and renovation. Entrance road gates should remain closed except when a rider opens and closes them for vehicle access. Plan for turnaround areas when placing gates, so gate closures do not create dead ends. Figure 10–12 shows the perimeter fence and gates in a campground with loops and turnarounds.

Figure 10–12—Fencing and gates in an equestrian recreation site.

Road gates commonly range from 16 to 20 feet (4.9 to 6.1 meters) wide. Two-lane roads normally have two gates. Figure 10–13 shows a gate suitable for an area with a high level of development. A standard gate is preferred in areas with low to moderate development (figure 10–14). A farm gate is more appropriate for areas with low development (figure 10–15).

When trails or attractions are outside the recreation site, provide a smaller trail gate beside the road gate. The additional gate is necessary when a cattle guard blocks the exit (figure 10–16). Trail gates are easier for riders to open and close than large road gates.

Figure 10–13—This pair of gates is suitable for a recreation site

with a high level of development.

Figure 10–14—A gate commonly used by the Forest Service in

recreation sites.

Figure 10–15—Farm gates are used in some areas for horse trails.

Figure 10–16—A cattle guard with an adjacent trail gate.

Stepover Gates

A road gate can have a low section—or stepover—that keeps wheeled vehicles out, but allows pedestrians and equestrians to pass (figure 10–17). Gates with stepover bars are not effective perimeter closures because a loose horse or mule may walk or jump over the bars, as might wildlife or cattle.

Figure 10–17—This prototype road closure gate allows trail stock

and pedestrians to pass, while restricting many motor vehicles.

This trail gate is not accessible to people with disabilities because the bar

across the opening is higher than 2 inches. See Chapter

12—Providing Signs and Public Information for sign details. For long description

click here.

Trail stepover gates have a horizontal bar or other device placed across the tread to deter unauthorized use. Figure 10–18 shows a rural trail with a narrow V-gate and a stepover bar. Land managers commonly use stepover gates to discourage motor vehicles on nonmotorized trails. Stepover gates are not foolproof. While it is difficult to get an off-highway vehicle (OHV) across them, it is easy to lift motorbikes over them. Recreationists sometimes fill the gap between the ground and the bar with soil, creating a ramp for motor vehicles. One challenge facing land management agencies is designing a stepover gate that allows a person with disabilities to pass through the barrier while excluding OHVs.

Figure 10–18—Riders, pedestrians, and mountain bikers can pass

through this relatively narrow V-gate on a rural trail, but ATVs

are restricted. The gate is not accessible to people with disabilities

because it is narrower than the minimum width required for

passage of a wheelchair—32 inches—and the bar across the

opening is higher than 2 inches.

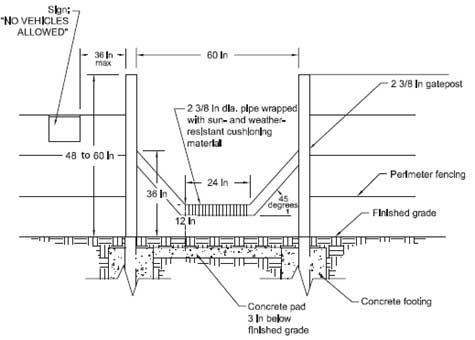

Many horses and mules routinely use stepover gates; others are hesitant to do so. Wrapping the bar with cushioning material will dampen the noise when an animal's hoofs contact the bar. The preferred height for the stepover bar is 12 inches (305 millimeters). The maximum is 16 inches (406 millimeters). When a bar is too high, stock may jump over it, unseating inexperienced riders. On horse trails where riders have limited experience, a bar lower than 12 inches (305 millimeters) may be appropriate. Tread surfaces on both sides of stepover gates wear down or become compacted over time, leaving the bar higher from the ground (figure 10–19). Short stepover bars accommodate trail compaction, but may allow unauthorized trail users to pass. Higher stepover bars may require frequent maintenance because of tread wear. To reduce tread wear at a stepover gate, install a concrete pad below grade and cover it with tread surface material (figure 10–20).

Figure 10–19—As heavy traffic wears the tread down, negotiating

stepovers may become more difficult for all users. This trail gate

is not accessible to people with disabilities because the bar across

the opening is higher than 2 inches.

Figure 10–20—A stepover gate for nonmotorized trail users. This trail gate is not

accessible to people with disabilities because the bar

across the opening is higher than 2 inches.