Discover History

The history of the Dakota Prairie Grasslands is a story of human and natural change spanning thousands of years, from prehistoric Native American cultures to European settlement and beyond. The grasslands were initially home to diverse Native American groups who lived as hunters and gatherers and later practiced agriculture and developed distinct cultural traditions. Following the arrival of Europeans, the area became a site of fur trading, then a rich agricultural land, and continues to be a region of farms and ranches.

Native American Presence in the Grasslands

For thousands of years, various Native American groups inhabited the Dakota Prairie Grasslands. Evidence of their presence dates back around 11,500 years Before Present (BP), with sites indicating Paleoindian, Plains Archaic, and Plains Woodland cultures.

Figure 1. A prehistoric painting of humans hunting a bison with a spear on a sandstone.

(Licensed photo by rdonar/AdobeStock photo.)Paleoindians, 11,500 to 7,500 years BP

Paleoindians were the first humans to inhabit North Dakota, arriving roughly 11,000 years ago at the end of the Ice Age. They were hunter-gatherers, primarily big game hunters who followed large herds of animals like mammoths and bison (Figure 1). Paleoindian artifacts, including finely crafted Clovis points, have been found in North Dakota, indicating their presence.

The Plains Archaic, 5,500 B.C. to 400 A.D.

The Plains Archaic period in North Dakota, roughly 5,500 BC to 400 A.D., represents the region's early stage of human civilization. These people descended from the Paleoindians and developed distinct cultural practices and tools, including using Knife River flint. They adapted to the Great Plains environment by hunting and gathering, leaving cultural evidence in stone tools and other artifacts.

Plains Woodland, 600 A.D. to 1200 A.D.

The Plains Woodland cultures in North Dakota represent an early civilization characterized by hunting, gathering, and agricultural practices. They are broadly categorized as Early, Middle, and Late Plains Woodland, the latter beginning around 600 A.D. to 1200 A.D., which shifted towards more permanent settlements, established villages, and agricultural practices. Women cultivated crops like corn, beans, and squash.

Equestrians and the Fur Trade, 1780 to 1880

Figure 2. A plains Native American hunts bison on horseback.

(Licensed illustration by Mannaggia/AdobeStock photos.)The Great Plains experienced significant cultural and economic transformation during the 18th and 19th centuries when Europeans introduced horses and initiated the fur trade.

The introduction of horses revolutionized Native American culture, improving bison hunting, a crucial food, clothing, and shelter sources. They also made the movement of goods and people over vast distances easier, increasing trade opportunities and connecting different tribes. Horses also contributed to developing a more nomadic lifestyle among some Plains tribes (Figure 2).

The fur trade introduced European goods like beads, knives, and blankets in exchange for Native American pelts. European traders competed, establishing trading posts and relying on Native American supplies.

Gold Rushes, Railroads, Mid-to-Late 1800s

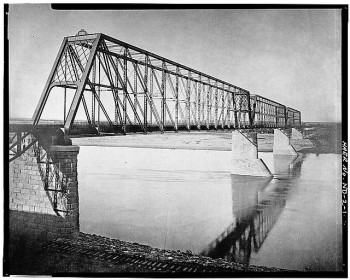

Figure 3. The 1883 Bismarck Bridge was a significant structure built by the Northern Pacific Railway (NPRR) to connect the railroad's east and west sides of the Missouri River and was the first bridge across the river in the Bismarck-Mandan area in Burleigh County, North Dakota.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress)During the mid-to-late 1800s, gold rushes and railroads brought miners, traders, and homesteaders to the region, transforming the landscape and culture.

Railroads played a crucial role in facilitating westward expansion by providing transportation and cheap land, attracting settlers, and promoting bonanza farming, which refers to large-scale, commercial wheat farming operations.

The Bismarck Bridge railway crossing was crucial for opening up the northwestern United States and facilitating westward expansion. Built by the Northern Pacific Railway between 1880 and 1883, it connected Bismarck and Mandan across the Missouri River. The bridge was a key component in the railroad's westward push, enabling the movement of goods and people and contributing to the growth of towns along the tracks (Figure 3).

The western expansion pushed the Northern Plains tribes into ever smaller remnants of their former homelands. Treaties between the government and resident tribes were made and broken by unscrupulous government agents and traders who often cheated and mistreated Native Americans.

Sibley, Sully, and the Sioux, 1862 to 1863

Figure 4. Brigadier General Henry Sibley shown here.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-14964.)The Sioux and other tribes responded to European exploitation and maltreatment with increasingly militant attempts to defend their homes and cultures. Tensions peaked in August 1862, and the resulting uprising in Minnesota Territory left 450 – 800 settlers and soldiers dead.

Governor Alexander Ramset sent Brigadier General Henry Sibley (Figure 4) with 1,400 soldiers to suppress the uprising. Many Santee were captured, and some fled west to join other Sioux bands.

The military, led by Sibley and Brigadier General Alfred Sully, pursued the Santee into the Dakota Territory, where Sibley fought several battles in July and August 1863. In September, Sully's attack on a Sioux village at Whitestone Hill resulted in more Native American deaths than any other conflict on the Northern Plains.

Battle of the Badlands, August 1864

Figure 5. Pictured here is Brigadier General Alfred Sully.

In June 1864, another expedition under Brigadier General Alfred Sully (Figure 5) left for Rice, Dakota Territory, to punish the Sioux further and establish military posts in the region; this was the first expedition to traverse the badlands.

Sully's column included:

- 2200 soldiers (Cavalry, mounted infantry, and artillerymen).

- 70 white and Native American scouts.

- 400 freight wagons.

- A cattle herd.

The procession was trailed by two civilian wagon trains of settlers bound for Montana and Idaho gold fields.

Sully's detachment engaged the Sioux (a coalition of Lakota, Yanktonai, and Dakota Native American tribes) at Killdeer Mountain on July 28th, then followed what is now called Sully Creek to the Little Missouri River.

On August 8, 1864, Sully's troops were spread across the Northern Plains in a long column stretching nearly three miles and began receiving Sioux sniping fire along the procession throughout the day. They stopped and camped for the night at a waterhole to resupply with water and fought of repeated Sioux incursions. The field is now the location Sully's Waterhole Interpretive Site.

Over the next three days, Sully fought a series of skirmishes with the Sioux that became known as the Battle of the Badlands on near Square Butte.

Although the battle was not described as overly violent or bloody, it did result in casualties on both sides. Sully estimated approximately 100 Native American warriors were killed (he may have exaggerated). Three US soldiers were killed, and an additional ten were wounded. Sully also destroyed the Native American encampment, including tipis and food supplies.

The Battle of the Badlands Interpretive Site now stands to commemorate the events. It's a 1,220-acre site within the Little Missouri National Grassland that features interpretive displays explaining the battle's events. The site also preserves portions of military trails from 1864 and 1876 and the 1876 Custer's Snow Camp (a nearby interpretive site) as he marched toward his final and ill-fated battle at Little Bighorn.

Northern Pacific Railroad Surveys, 1871 to 1873

Figure 6. Colonel David Stanley in an early photographic image.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-72683.)In 1864, the Northern Pacific Railroad promoted a railway plan to link the Great Lakes and Puget Sound. The Sioux, having witnessed the decimation of bison herds brought by railroads farther south, were determined to prevent the construction of rail lines west of the Missouri River. Their attacks made military protection of railroad survey parties necessary.

Major Joseph Whistler accompanied Northern Pacific Railroad surveyors on their 1871 reconnaissance to locate the best route across the northern Dakota Territory into the Montana Territory. This expedition is thought to have followed Davis Creek to its confluence with the Little Missouri River.

In 1872, Colonel David Stanley (Figure 6), accompanied by 600-foot soldiers, formed a survey party that attempted to avoid the badlands by traveling about 25 miles south of Whistler's route. The southerly route was even worse than the 1871 route, so they returned east via Davis Creek.

In 1873, Stanley's force of almost 2,000 men (including Custer's 7th Cavalry), 275 wagons, and a cattle herd escorted a third survey party on Whistler's 1871 route west from Fort Abraham Lincoln (across the Missouri River from Bismarck) into South Dakota's Black Hills.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, June 1876

Figure 7. George Armstrong Custer, in uniform, seated with his wife, Elizabeth "Libbie" Bacon Custer, and his brother, Thomas W. Custer, standing in the rear.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-114798.)The US government ignored the 1868 treaty to get the Lakota Sioux to cede the Black Hills (South Dakota) to gold seekers pouring into the area. The Sioux were told to report to their Indian agencies by January 1876 or be considered hostile. When the order was ignored, the government sent the military to enforce it.

In May, Brigadier General Alfred H. Terry headed west from Fort Abraham Lincoln with 1,108 officers and enlisted men, 45 Native American scouts and interpreters, and 190 civilian employees, as well as a wagon train, pack train, spare horses, a cattle herd, and a heavy weapons platoon. The detachment included most of Brigadier General Custer's 7th Cavalry.

They entered the badlands on May 27 near Easy Hill, continued down Davis Creek, and ascended Custers Wash before reaching the uplands above the Little Missouri River. However, on May 30, 1876, an unexpected snowstorm dropped six inches of white sloppy snow, which delayed Custer and his men for three days. The area is now known as Custer Snow Camp. Later, they continued west into Montana toward an ill-fated encounter at Little Bighorn.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, aka Custer's Last Stand, occurred on June 25-26, 1876. Custer's 7th Cavalry Regiment engaged the combined forces of Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes. Custer and all the men under his immediate command were killed, marking a major turning point in the relationship between the US and Native American tribes.

The Custer Trail Auto Tour is a scenic self-guided tour through the Little Missouri National Grasslands that follows the path of historical military expeditions, including George Armstrong Custer (Figure 7) and the 7th Cavalry.

The Battle of Slim Buttes, September 1876

Figure 8. A wounded man is carried away from The Battle of Slim Buttes on a horse drawn stretcher.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-DIG-stereo-1s00439)Brigadier General George Crook was also sent to Montana that summer to pursue the Lakota Sioux, who refused to go to the reservation. From there, his unit traveled east through the North Dakota badlands to South Dakota, where they engaged the Sioux in The Battle of Slim Buttes in September 1876.

The battle was the first military victory for the US Army during the Great Sioux War following Custer's devastating defeat at Little Bighorn. It demonstrated the army's ability to fight and, along with subsequent actions, contributed to the eventual demoralization of the Sioux and Cheyenne.

The battle was a turning point in the Great Sioux War, leading to further military actions and negotiations between the US government and the Sioux tribes.

The event featured a few notable figures from the US Army and the Lakota and Cheyenne nations. Crook faced off against Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, and other Sioux chiefs. Another key figure included General Phillip H. Sheridan (an American Civil War leader known for the Burning of the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia).

Three American soldiers were killed: two cavalrymen and one civilian scout (Figure 8). Additionally, there were likely more American casualties among the scouts, who were not all killed, but wounded or captured. An estimated least 10 Sioux were killed.

The Dust Bowl, 1920s to 1930s

Figure 9. Black Blizzards of the 1930s Dust Bowl were severe dust storms caused by drought and erosion that turned the sky black. Strong winds carried the dust, which covered everything in its path and was so thick that it reduced visibility to near zero. The image here is a Black Blizzard in Gregory, South Dakota, in 1934.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-95674 )Following the Great Sioux War, westward expansion increased, and the grasslands experienced a significant transformation. Initially, the grasslands were dominated by native grasses, supporting a diverse wildlife ecosystem. However, westward expansion led to agricultural development of the prairies.

Farmers plowed up large areas of the prairie, replacing the deep-rooted native grasses with shallow-rooted crops like wheat, making the soil more susceptible to wind erosion. The drought, combined with the lack of deep-rooted grasses, dried out the topsoil and became powdery, making it easy for the wind to carry away.

The erosion resulted in massive dust storms occurred during the period known as the Dust Bowl. These storms, often described as black blizzards (Figure 9) covered vast areas of the Great Plains, including North and South Dakota. The massive dust storms damaged crops and livestock and ultimately contributed to economic hardship and population decline in the region.

The federal government reacquired more than 11 million acres of submarginal land to stabilize the economy and restore devastated lands. Eventually, more than five million acres were transferred to the Forest Service.

Post-Dust Bowl, Denbigh, and Beyond

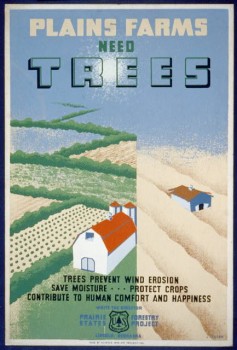

Figure 10. Shown here is a Work Projects Administration Poster that highlights the importance of trees to the farming community. The advert notes that benefit farmers by preventing wind erosion, saves moisture, protects crops and contributes to human comfort and happiness,

(Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-USZC2-815 )After the Dust Bowl, the Forest Service and other federal agencies managed the grasslands to prevent further soil erosion and improve their ecological conditions. They focused on controlling land use, establishing experimental forests like Denbigh, and implementing soil conservation practices.

The goal was to ensure the long-term health of the grasslands and prevent similar environmental disasters in the future. Programs like the Soil Erosion Service (later renamed Natural Resources Conservation Service) and the Prairie States Forestry Project focused on soil conservation and reforestation to prevent future erosion.

New techniques, such as crop rotation, contour plowing, and windbreaks, were implemented to help stabilize the soil. The government also provided financial assistance to farmers, offering payments per acre to adopt new conservation techniques (Figure 10).

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was established in 1933 and played a large role in forest management, planting trees on reforestation projects, managing fire prevention, and improving overall forest health. The CCC provided valuable jobs and economic stimulus, particularly for young, unemployed men during and after the Dust Bowl. They received a small paycheck, meals, housing, and educational opportunities. The CCC was terminated in 1942 as the United States entered World War II.

Figures 1 - 10 Photo Gallery

Click an image to view the photo gallery in full-screen size and read the descriptive captions.

Additional Historical Resources About the Grasslands

Prehistoric Periods in the Grasslands

The Prehistory on the Dakota Prairie Grasslands: An Overview, by Mervin G. Floodman MA, provides a more in-depth exploration of the prehistorical periods, including the Paleoindian (11,500-7,500 BP), Plains Archaic (7,500-2,400 Before Present), and Plains Woodland (2,400 BP-1200 AD).

Plains Villages to the 20th Century in the Grasslands

The History of the Dakota Prairie Grasslands - An Overview 2011 by Thomas J Turck MS, RPA, focuses primarily on the period from 1700 to 1950.

Archaeology and Cultural Resources

Archaeology and Cultural Resources

The Dakota Prairie Grasslands boasts a rich cultural history. Visit our Archeology and Culture Resources page for links to Historical Interpretive Sites in the Grasslands