Preview Draft Assessment

Help Shape the Future of the Bridger-Teton

The Bridger-Teton National Forest is seeking public input on its draft assessment and potential species of conservation concern. We invite you to participate in this open comment period which ends on August 24, 2025.

What is an Assessment?

The draft assessment marks the first step in updating the Forest plan and provides a "state of the Forest," summarizing current ecological, social, and economic conditions and trends affecting the Bridger-Teton National Forest. It provides the foundation to inform the next steps in the forest planning process.

It is not a decision document and is the first step in the three-tiered forest planning effort: Assessment, Plan Revision, and Monitoring.

The central question is: Do you think the draft assessment provides sufficient information to help identify where the Forest should focus on updating its Forest plan?

Process & Open Comment Period

Three documents are available for review and comment on the Bridger-Teton Planning webpage:

- Draft Assessment

- Supplemental Assessment Information for the Bridger-Teton

- Potential Species of Conservation Concern

How do I access the documents?

The documents are available via the links above, by scanning the code, or by visiting the Bridger-Teton Planning webpage at https://www.fs.usda.gov/r04/bridger-teton/planning (also linked below).

Where can I provide comments?

You can submit comments on the Draft Assessment, Supplemental Assessment Information for the Bridger-Teton, and Potential Species of Conservation Concern via the Bridger-Teton Planning webpage or https://cara.fs2c.usda.gov/Public/CommentInput?project=63628 (also linked below).

How can I see what other people are commenting?

A public comment reading room is available, where you can view all comments that have been submitted for the Draft Assessment, Supplemental Assessment Information for the Bridger-Teton, and Potential Species of Conservation Concern via the Bridger-Teton Planning webpage or https://cara.fs2c.usda.gov/Public/ReadingRoom?project=63628 (also linked below).

View Public Comment Reading Room

When is the comment deadline?

We invite you to participate in this open comment period which ends on August 24, 2025.

What input would be helpful?

Do you think the Draft Assessment provides sufficient information to identify what the Forest should focus on as management direction is updated? Does the information on the status and trends for various topics seem accurate?

Forest Plans provide comprehensive, strategic, and integrated resource direction. They function like a county comprehensive plan and are used to guide all decisions about future projects and uses on the National Forest.

Why update the Plan?

Much has changed ecologically, socially, and economically since 1990. With these changes, an update of the forest plan is needed.

What changes have you noticed since 1990?

(Click image to view Map)

| Desired Future Conditions (DFC) | Theme | Acreage | % of Forest | Did we make progress? What has changed since 1990? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1B: Substantial commodity resource development with moderate accommodation of other resources | Managed for timber harvest, oil and gas and other commercial activities with many roads | 182,993 | 5.3% | Nine oil and gas wells have been drilled since 1990. 48% of all timber harvest units on the Forest occurred in this DFC. |

| 2A, 2B: Non-motorized and motorized recreation areas | Managed to give a quiet, almost primitive recreation experience (2A). Managed to give a motorized recreation experience (2B) | 199,079 | 5.8% | Most of the 2A area retains a primitive or semi-primitive recreation setting and is managed for non-motorized recreation in the summer. Most of the 2B area is managed for motorized recreation in winter and provides a semi-primitive motorized setting in the summer. |

| 3: River recreation | Managed to give a river and scenic recreation experience | 74,258 | 2.1% | Eligible rivers in the amended 1990 plan have retained their identified values and many rivers originally eligible are now congressionally designated as wild and scenic rivers. |

| 4: Special emphasis area for municipal water supply | Managed to protect municipal water supply | 43,118 | 1.2% | While municipal water supplies have largely been protected, not all standards have been implemented. Afton and Stary Valley Ranch have recently begun to treat their water. |

| 6A-6D, 6S: Wilderness, Wilderness Study Areas, and Wild Rivers | Mostly pristine areas where the presence of people is rarely or never noticed | 1,409,570 | 40.8% | The wilderness character of existing areas has largely been preserved with increasing summer recreation a growing concern (Bridger Wilderness). The bio-physical character of the WSAs has been maintained but snowmobile and mountain bike use have become more contentious. |

| 7A, 7B: Grizzly bear habitat recovery (with scheduled timber harvest in DFC 7A) | Managed to provide forage and security for recovery of grizzly bears with some resource development in 7A | 73,436 | 2.1% | Three timber harvest units have occurred in the 7A area since 1990. Grizzly bear population has improved dramatically in both areas. |

| 8: Environmental education about integrated multiple use | Managed to provide conservation and EE; study of resources/forest management | 22,039 | 0.6% | This area was established for education and resource studies through Teton Science Schools. A field camp was initially set up, but the focus of the school later changed. |

| 9A, 9B: Developed and admin sites, special use recreation areas | Managed for campgrounds, admin sites (9A). Managed for permitted recreation sites such as ski areas (9B) | 14,970 | 0.4% | Some campgrounds and guard stations have been improved but ability to maintain older facilities and water systems has declined. Substantial investment in improvements has occurred at JHMR and Snow King resorts. |

| 10: Simultaneous development of resources, human experiences, big game and wildlife support | Managed to allow for some resource development and roads while having no adverse and some beneficial effects on wildlife | 767,214 | 22.1% | 280 timber harvest units have occurred in this area since 1990 with 12% of projects also including a wildlife habitat improvement purpose. |

| 12: Backcountry big game hunting, dispersed recreation, wildlife security | Managed for high-quality wildlife habitat and escape cover, big game hunting opportunities, dispersed recreation | 680,886 | 19.6% | Opportunities for public and outfitted big game hunting have been maintained. Seasonal winter and motorized travel restrictions, Path of the Pronghorn are examples of projects in this area. |

The Draft Assessment is the first step in the multi-year process to update direction to the 1990 Forest Plan. Given the length of the process, patience and perseverance are crucial.

(Click image to view Infographic)

Infographic Text:

Forest Plan Revision Sequencing

- Draft Assessment & Proposed Species of Conservation Concern

- Need for Change

- Wild & Scenic Rivers Eligibility

- Wilderness Inventory & Evaluation

- Proposed Forest Plan

- Draft Environmental Impact Statement

- Final Environmental Impact Statement & Draft Decision

- Objection Process

- Final Record of Decision

Overview of Draft Assessment & Potential SCC Content

Chapter 1 - Introduction

- Forest Setting

- Distinctive Roles and Contributions

- Management Constraints and Opportunities

Chapter 2 - Ecological Sustainability and Diversity of Plant and Animal Communities

- Ecosystem Drivers and Stressors

- Connectivity

- Terrestrial Ecosystems

- Aquatic, Wetland, and Riparian Ecosystems

- Watersheds and Water Resources

- Air Resources

- Diversity of Plant and Animal Species

- Geological Resources and Hazards

Chapter 3 - Socioeconomic Elements and Multiple Use

- Social and Economic Conditions

- Areas of Tribal Importance

- Fire Management

- Recreation Lands and Access

- Scenic Character

- Roads, Trails and Facilities

- Land Ownership

- Production of Natural Resources (Forest Management, Range Management, Energy and Minerals)

- Protected Lands and Resources (Congressionally Designated and Administratively Protected Areas, Cultural Resources)

References

Identifying Species of Conservation Concern (SCC) is part of the 2012 Planning Rule approach to meet the requirement to “provide for diversity of plant and animal communities based on the suitability and capability of the specific Forest.”

For a species to be considered a Species of Conservation Concern they must be native and known to occur within the Forest. They also must have best available scientific information that indicates substantial concern regarding long-term persistence in the Forest.

Proposed Species of Conservation Concern (SCC), Bridger-Teton National Forest

- 6 wildlife species (sage grouse, western toad, Columbia spotted frog, black rosy finch, Gillette’s checkerspot, western bumblebee)

- 5 fish species (Colorado cutthroat trout, Snake River fine-spotted cutthroat trout, flannelmouth sucker, northern leatherside chub, roundtail chub)

- 14 plant species (Payson’s milkvetch, particular moonwort, scalloped moonwort, beautiful sedge, woolly fleabane, fragile rockbrake, Wyoming tansymustrad, fourpart dwarf gentian, Vasey’s rush, mountain wild mint, Greenland primrose, pink campion, Teton wirelettuce, largeflower triteleia)

Nearly 200 species were evaluated as part of this process and can be reviewed below. Comments on the proposed list are encouraged.

(Click image to view Map)

Water and snow are one of four qualities that make the Bridger-Teton distinctive within the larger region.

- Headwaters of our nation’s most relied upon river systems – Snake (Columbia), Green (Colorado), Yellowstone (Missouri)

- Stronghold for native fisheries (4 out of the 6 native cutthroat trout species)

- Abundant snowfall and glaciers; snow predicted to persist longer on the Bridger-Teton than elsewhere

- 5,548 miles of perennial streams

- 344 lakes, 5 reservoirs

- Unique springs, waterfalls, Parting of the Waters

Water resources serve important socio-economic needs:

- 707 active water rights

- 21 Wyoming state zone 1 protection areas that include water systems that serve Alpine, Pinedale, and Afton

- Important irrigation, stock-water, ranching uses

- The types of water uses today are similar to 1990 but demand for water use has increased

Wyoming State Class 1 designation to protect water quality include waters within designated Wilderness, the main stem of the Snake River above Highway 22, the main stem of the Green River above New Fork River, the main stem of Sweetwater River above Alkali Creek, Granite Creek, Fish Creek (near Wilson), and Fremont Lake. Water quality is considered good but sections of eight streams downstream of the Forest are impaired.

(Click image to view Map)

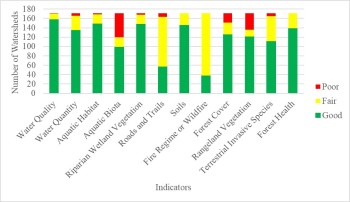

Of the 171 watersheds on the Forest, 157 are functioning properly, 14 are at-risk, and none are impaired. Aquatic ecosystems are generally functioning within the natural range of variation but climate change (warming temps, drought), along with roads/trails, recreation, wildfire, invasive plants, non-native fish, grazing, and increasing water demand are stressing aquatic ecosystems and fisheries.

The majority of remaining cutthroat trout habitat exists in high-elevation, headwater portions of their historic range, mostly on the National Forest. An intact native fish assemblage is an indicator of aquatic system function and health and supports a robust recreational fishery. The Bridger-Teton is considered to possess the most intact habitat for boreal species and cold water fisheries.

Wildlife and fisheries are one of four qualities that make the Bridger-Teton distinctive within the region.

- The Bridger-Teton supports most of the mammal and bird species that were present before the 1880s.

- Healthy populations of predator species – a strong indicator of a productive ecosystem.

- 74 mammal species, 355 bird species, 12 reptiles and amphibians, 25 fish species.

- Four core herds of bighorn sheep, which account for 85% of state’s bighorn population.

- Numerous long-distance ungulate migration corridors including the first federally designated corridor (Path of the Pronghorn). Connectivity models reveal important movement corridors for forest specialists are present throughout the Bridger-Teton.

- Only home for the endangered Kendall Warm Springs dace.

- Center for much of the wildlife research in the U.S., wildlife galleries, filming, National Museum of Wildlife Art.

(Click image to view Map)

Rocky Mountain Subalpine Dry-Mesic Spruce-Fir Forest and Parkland is the dominant ecosystem type on the Bridger-Teton, occupying 35.4% of the acreage. The ecological integrity of ecosystems is assessed by looking at the natural range of variation (NRV). The NRV does not necessarily constitute a desired condition but ecosystems that are within their natural range of variation are assumed to be more resilient to current and future stressors.

The integrity rating for most of the terrestrial ecosystems on the Bridger-Teton is considered “moderate” and trending towards either “moderate” or “low” integrity into the future, mostly attributed to the influence of climate change. A primary current stressor is insect and disease related tree mortality, invasive species, and fire suppression.

Recreation and Wildlands are one of four qualities that make the Bridger-Teton distinctive within the region.

- 2.2 million annual visitors, most heavily visited forest in Wyoming.

- 2,807 miles of summer trails, 668 miles of groomed winter trails. Trail system miles have increased 17% since 1990 – more motorized trails, frontcountry trails, Nordic trails

- Largest outfitter-guide program in the region (220 permits). Winter outfitted activity increased 146% since 2012, summer/fall outfitted activity increased 6% but summer/fall use still dominates (180,000 service days vs. 20,000)

- Winter recreation (skiing, snowmobiling), trail-based activities, and wildlife-fish based activities are particularly distinctive

- Open road miles are very similar to 1990 (1,561 today compared to 1,539)

- Recreation activity generates the most jobs and contributes the most to local economy (56% of jobs, 90% of special use receipts from the Forest)

- The shifting nature of recreation has been more dramatic than sheer amount of use (technology, info sources, demographics)

- Huge deferred maintenance backlog for roads, trails, and facilities

The Challenge Ahead

- Easily accessed day-use areas, road-accessible camping areas, and key destinations popularized through social media will face increased pressure.

- Social conflict will be more challenging to address than ecological effects.

- Electric technology will blur the line between motorized and non-motorized use.

- Winter recreation planning to address non-motorized, motorized, and wildlife interests will be particularly challenging.

- A warming climate will increasingly affect recreation settings and opportunities.

The Forest Service uses the Recreation Opportunity Spectrum (ROS) to offer a range of recreation settings. Rather than disperse use, the goal is to provide a variety of opportunities, recognizing that not everyone seeks the same type of experience.

- Use is not evenly distributed and tends to be concentrated near road corridors, close to communities, adjacent to national parks, at resorts, and in nationally designated areas. Summer use is more dispersed than winter use.

- 74% of the forest offers a primitive or semi-primitive, non-motorized (undeveloped) setting in the summer, whereas 52% of the forest offers a semi-primitive, motorized (undeveloped) setting in the winter.

The Forest Plan Opportunity

Some Key Questions will be:

- What is the desired and sustainable mix of recreation experience settings both summer and winter?

- How much change is acceptable?

- What monitoring metrics would be most useful to track change?

(Click image to view map)

(Click image to view map)

(Click image to view map)

Congressionally designated areas reinforce the national significance of the Bridger-Teton's natural assets. The Bridger-Teton offers more area more than 3 miles from a road (primitive setting) than any other Forest in the region; backcountry areas larger than 5,000 acres exist on the Bridger-Teton but are rare elsewhere.

41% of Forest is Congressionally designated, (1.298 million acres Wilderness, 111,700 acres Wilderness Study Area, 315 miles W&S River, 231 miles of National Scenic and Historic Trails). The Teton and Bridger Wildernesses were two of the original 1964 Wildernesses.

41% of Forest is administratively protected, mostly as Inventoried Roadless Areas. Other administratively protected areas include the “Parting of the Waters” (NNL), the Gros Ventre Geological Area, 4 Research Natural Areas, 2 Special Interest Areas, 81 miles of scenic and backcountry byways, and 92 miles of National Recreation Trail.

Forest plan direction for Wilderness needs to be updated to incorporate the requirement to preserve wilderness character and address current concerns. Wild & Scenic River direction is current as of 2014. Direction for Wilderness Study Areas, National Trails and administratively protected areas are absent.

(Click image to view map)

Cultural connections: way of life is one of four qualities that make the Bridger-Teton distinctive within the region.

- Ancestral homeland for numerous tribes who hold a 12,000-year-old relationship with the land. Current tribal practices include gathering plants and teepee poles, hunting, fishing, and visiting sacred places. The forest is where tribes such as the Eastern Shoshone, the Shoshone Bannock, and other tribes, hunted, lived, traveled and called home, especially in the warmer months.

- Euro-American settlers arrived in the late 1880s with Big Piney the oldest permanent settlement.

- Counties encompassing the Forest have histories and socio-economic community character closely tied to ranching, wildlife (elk and beaver), recreation/ tourism, and resource use.

- Roughly 75% of annual visitor use comes from people who live less than 50 miles away from the forest and 48% visit the forest more than 50 times per year.

- 30% of local county residents report that 11% or more of their household needs are derived from the forest (firewood, hunting, fishing)

- The nationally recognized Green River Drift symbolizes the historic and on-going relationship between ranchers and the forest.

(Click image to view map)

93 active allotments, 15 forage reserves, 18 vacant unavailable allotments, and 29 closed allotments.

Large carnivore conflicts, permit waivers back to the Forest Service without preference, and separating domestic sheep from bighorn sheep are the primary drivers for the reduction in active allotments.

105 permittees graze 31,807 cattle and 39,945 sheep. Livestock numbers have declined since 1987 when about 40,000 cattle and 78,000 sheep grazed in the Forest.

Monitoring for 18 allotments in the Pinedale and Big Piney districts show an average of 12% utilization on key forage species and an average of 9’ stubble height on riparian plant growth; both metrics well within thresholds.

Monitoring for 13 allotments on the Kemmerer and Greys River District show 30% are trending upward, 60% are stable, and 10% are trending downward.

(Click image to view map)

The fire regimes on the Bridger-Teton National Forest are mostly characterized by moderate to long interval frequency fire (50 to 300 years); large stand-replacing fires are part of this fire regime.

With a warming climate, the trend is for large fires to happen more often and for fire seasons to be longer, especially in the fall.

Since 1952, 3,470 fires have been detected with 56% attributed to lightning and 44% human-caused, mostly due to campfires.

The Bridger-Teton adopted a prescribed burning program in 1974 and since then 85,000 have been treated; 14,000 acres have been mechanically treated.

The extent and complexity of the wildland-urban interface has increased creating challenges for fire fighters at all levels.

An interagency “all-lands” approach (with county CWPPs) is in place for all 5 counties. To prepare communities to live with fire, the future includes integrated fuels treatments, managing smoke, fire wise programs for structures, and fire prevention/outreach.

Role of forest management: restore and maintain forest structure

to be more resilient, reduce fuels at strategic locations, restore or enhance wildlife habitat, provide commercial and personal use products.

Between 2011 and 2018, approximately 36% of trees on the Forest died, primary from bark beetles, white pine blister rust, and fire.

Timber harvest has declined, as have the number of forest product manufacturing facilities (from 27 in 2000 to 14 in 2019).

Just under 12,000 acres has been harvested via commercial timber sales since 1990 along with about 114,000 acres treated to reduce hazardous fuels. 69% of commercial harvest acres were treated with thinning, sanitation, or salvage cuts with salvage cuts associated with insect and disease the most common recent treatments.

Firewood volume has increased with an average of 10,239 cords sold each year. Christmas tree permits average 2,348 per year but have been declining as have permits for tree transplants.

Table: Estimated annual mortality of trees, 2011-2018

| FIA Species Group | Number of Trees |

|---|---|

| Douglas-Fir | 469,823 |

| Subapline Fir | 2,044,923 |

| Engelmann and Blue Spruce | 897,186 |

| Lodgepole Pine | 3,374,706 |

| Whitebark and Limber Pine | 1,665,737 |

| Cottonwood and Aspen | 704,217 |

| Total | 9,156,591 |

Draft Assessment Public Overview Slide Deck

Preview the Draft Assessment with this public overview slide deck summary to learn about key findings included in the document, the forest planning process in general, and how you can provide public comments.