Spruce Needle Casts and Blights

Lirula macrospora (Hartig) Darker

Lophodermium piceae (Fuckel) Hӧhn

Rhizosphaera pini (Corda) Maubl. or Rhizosphaera kalkhoffii Bubák

Host(s) in Alaska:

Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis)

white spruce (P. glauca)

black spruce (P. mariana)

Lutz spruce (P. glauca x P. sitchensis)

Habitat(s): spruce needles

Three fungi that cause needle casts and blights of spruce occur throughout much of Alaska (Detection Map), although they are rarely noticeable. Elevated Rhizosphaera needle blight symptoms were noted again this fall in Southeast Alaska near Juneau and Wrangell. Disease caused discoloration and needle loss in the interior and lower crowns of affected trees. The Capitol Christmas tree was sourced from the Wrangell Ranger District in 2024, and an alternative tree was harvested because the original selection was symptomatic. Work continues to verify the species of Rhizosphaera on spruce in Alaska.

2024 Ground Detection Survey Observations: 11 total observations of L. macrospora: 1 near Anchorage, 1 near Cordova, 2 near Juneau, 3 near Wrangell, and 4 near Ketchikan. Four observations of L. piceae, all near Wrangell. Five observations of Rhizosphaera sp., all near Juneau. These diseases were not recorded during aerial detection surveys in 2024.

2024 iNaturalist Observations: There was one research grade observatoin of L. macrospora near Anchorage.

These diseases can be distinguished based on the fungal fruiting structures on needles, and (when severe) also on the pattern of foliage discoloration. Symptoms are often most severe in the lower and interior tree crown, where persistent needle wetness promotes foliage disease. Rhizosphaera and Lirula needle casts are considered more damaging than Lophodermium needle cast in Alaska.

Lirula: Fruiting structures are black and elongated on the undersides of needles. Spores are released from mature fruiting structures on infected two-year-old needles in spring to infect newly emerging foliage during shoot elongation. Red-brown foliage discoloration symptoms become apparent one year after infection, with needles turning tan-brown after two years. This results in a distinctive pattern of green new growth, red-brown one-year-old needles, and tan two-year-old needles, often interspersed with healthy foliage. Although usually not necessary, chemical control* is effective when applied around bud break. Thinning and pruning trees to increase air movement in the crown can reduce infection. Smaller trees are often more severely affected than large trees.

Lophodermium: Fruiting structures are black and elliptical, often with black zone lines crossing needles. Symptoms generally appear in older groups of adjacent needles. Damage may be more common on large trees compared to smaller trees in young-growth stands.

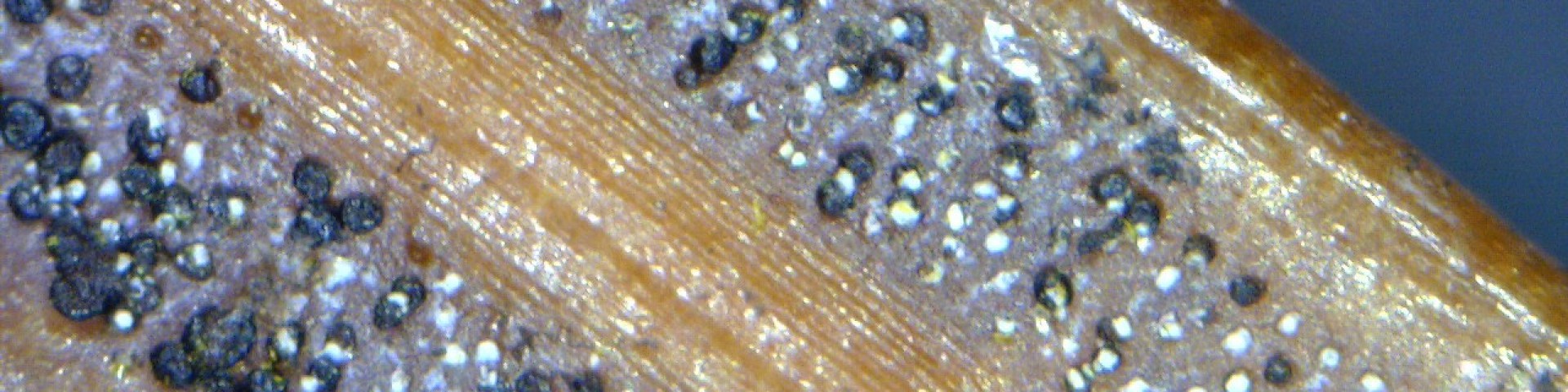

Rhizosphaera: Small black fruiting structures occupy pores for gas exchange (stomata) on needles (generally requires a hand lens for identification). Spores are rain-splash dispersed from fruiting bodies in spring (and summer if conditions are suitable), primarily infecting new needles. Red-brown foliage discoloration and premature needle shed symptoms become apparent in late summer and fall, 1.5 years after infection. Severely defoliated trees can lose nearly all of their >1-year-old needles, but associated tree mortality is rare. Outbreaks may develop when temperature and moisture conditions are favorable for dispersal and infection for multiple consecutive years.

*CAUTION: Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish or other wildlife-if they are not handled or applied properly. Use all pesticides selectively and carefully. Follow recommended practices for disposal of surplus pesticides and pesticide containers. Mention of a pesticide in this publication does not constitute a recommendation for use by the USDA, nor does it imply registration of a product under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act, as amended. Mention of a proprietary product does not constitute an endorsement by the USDA.

Between 1972 and 1984, spruce needle cast caused by Lophodermium piceae was the only spruce needle cast pathogen implicated in annual Forest Health Conditions in Alaska reports. It was said to be common in Southeast Alaska (1972), and noticeable north of Icy Bay and on the Kenai Peninsula, especially Homer (1982-1984).

From 1985 to 1991, spruce needle cast caused by Lirula macrospora occurred at moderate to high levels in coastal Alaska, prompting study of spore dispersal and symptom development (Hennon 1990). This disease was considered the most damaging of the three needle cast diseases. Elevated disease levels were noted on Sitka spruce in Southeast Alaska, white and Lutz spruce on the Kenai Peninsula and north of Anchorage, and Sitka spruce on Kodiak Island. In 1991, a fungicide study demonstrated that chemical control was effective when applied soon after bud break (though chemical control is not usually warranted). It was observed that disease is often most severe in stands in which spruce grows with red alder, perhaps due to soil nutrition. Lirula also caused moderate damage in 1994 (coastal Alaska), 1997 (Afognak Island across an estimated several thousand acres; at moderate to high levels in most areas in the range of Sitka spruce). In 2015 and 2016, damage from Lirula was noted at several locations in coastal Alaska (e.g., near Juneau, Kake and on the Kenai Peninsula).

Needle cast caused by Rhizosphaera sp. was observed on Sitka spruce throughout Girdwood, Twenty-mile and Portage Valleys south of Anchorage in 1992, but was thought to cause negligible damage in natural forest settings (problematic in nurseries and plantations; offsite plantings). However, in 1993-1994, Rhizosphaera occurred at damaging levels in coastal Alaska, killing lower and inner crowns of Sitka spruce near Juneau. Rhizosphaera needle cast returned to endemic levels until 2009, when it became epidemic on Sitka spruce for one year in many areas of Southeast Alaska: “the largest and most intense outbreak in memory.” Elevated disease levels were also observed from 2013 to 2015. Forest Health Protection is hoping to confirm the species identity of Rhizosphaera in Alaska, which may be R. pini or R. kalkhoffii.

Detection of spruce needle cast diseases is usually based on informal ground-assessments and permanent monitoring plots. Fall symptom development and lower crown symptoms preclude consistent detection during aerial survey.

Hennon, P. E. 1990. Sporulation of Lirula macrospora and Symptom Development on Sitka Spruce in Southeast Alaska. Plant Disease 74:316-319. Available here.

Juzwik, J.; O Brien, J. G. 1990. Premature Needle Loss of Spruce. NA-PR-01. [Radnor, PA]: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Area State & Private Forestry.

flickr Photo Gallery

Content prepared by Robin Mulvey, Forest Pathologist, Forest Health Protection, robin.mulvey@usda.gov.