Yellow-Cedar Decline

Effective beginning 06/04/2025: This website, and all linked websites under the control of the agency is under review and content may change.

Yellow-cedar decline is caused by fine root freezing injury. It occurs on sites with shallow soils and low snowpack. Yellow-cedar is uniquely vulnerable to this form of injury.

Tree Species Impacted in Alaska:

Yellow-cedar (Callitropsis nootkatensis (D. Don) Oerst. ex D.P. Little; formerly Chamaecyparis nootkatensis)

Damage: Yellow-cedar trees are killed by fine root freezing injury where there is insufficient snowpack to insulate roots from lethal cold temperatures during early spring cold events. Root and foliar tissue prematurely deharden in spring.

Summary

Click to access interactive map

- This interactive map displays the extent of yellow-cedar decline mapped across Southeast Alaska 1986-2024, including forests impacted earlier in the 1900s. The datasets used to produce the map are available for download to meet a variety of user needs.

- A Climate Adaptation Strategy for Conservation and Management of Yellow-cedar in Alaska synthesizes the ecology, value, taxonomy, and silvics of yellow-cedar; the causes of decline; active management opportunities; and the current and projected status of yellow-cedar in 33 management zones.

- Many affected yellow-cedar forests established under the colder climate of the Little Ice Age (1400-1850). Elevated mortality began in the late 1800s, spiked in the 1970s and 1980s, and continues today.

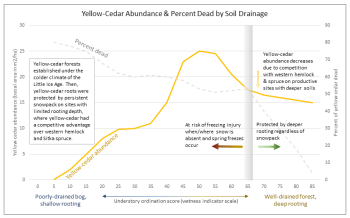

- Yellow-cedar is most competitive on wet sites, where open canopy conditions and concentrated rooting near the soil surface translate to greater exposure to soil temperature fluctuation in early spring. Fine root freezing injury occurs in the absence of insulating snowpack when surface soil temperatures drop below 23 °F (-5 °C).

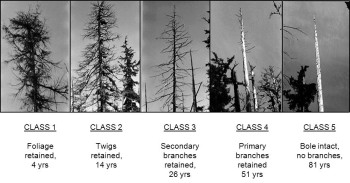

- Trees frequently survive 10-15 years after decline symptom onset. Impacted forests contain a mix of old dead, recently dead, dying, and live yellow-cedar trees.

- In severely affected forests, 20-30% of the yellow-cedar basal area survives. Residual cedars are presumably protected by microsite and/or tree genetics.

- Mortality may lead to diminished populations, but not extinction. Yellow-cedar has low rates of natural regeneration and recruitment.

- Yellow-cedar can be promoted through selective thinning and planting on sites with deep soils and persistent snowpack. Deer browse can limit regeneration.

- The durable decay resistance of yellow-cedar snags presents opportunities for salvage harvest.

- Yellow-cedar is not protected under the Endangered Species Act: view the full decision and species status assessment.

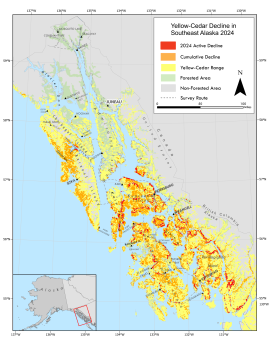

Current (2024) and cumulative yellow-cedar decline mapped by aerial detection surveys in Southeast Alaska with the modeled range of yellow-cedar.

(USDA Forest Service map by Robin Mulvey)- In 2024, 14,400 acres of active yellow-cedar decline were mapped during aerial detection survey. Crown discoloration and mortality from yellow-cedar decline was elevated this year in both unmanaged, old-growth forests and several young-growth stands, mostly in central and southern Southeast Alaska.

- In Prince William Sound, a few suspected dead yellow-cedar trees were mapped along Cedar and Granite Bays. These areas will be monitored and ground-checked when possible to verify the tree species and cause of death.

- In recent years, very small patches of yellow-cedar mortality have also been observed along the outer coast of Glacier Bay National Park near La Perouse Glacier, Finger Glacier, and Icy Point, but this area could not be aerially surveyed this year because of bad weather and has not been visited on the ground due to difficult access.

- Decline was first observed in young-growth stands managed for timber in 2013. To better understand the impacts of yellow-cedar decline in managed stands, monitoring plots were installed in 2018 in five young-growth stands with substantial decline symptoms on Zarembo, Kupreanof, and Wrangell Islands. The plots were remeasured in 2023 and 2024. Across 41 study plots, 6% of yellow-cedar trees were dead, up from just 2% in 2018. The highest mortality rate was observed in the stand on Kupreanof Island, where the percentage of dead yellow-cedar trees increased from 8% in 2018 to 30% in 2024. A further 16% of the live yellow-cedar trees in our plots had pronounced crown discoloration symptoms and are not expected to recover.

- More than 710,000 acres of yellow-cedar decline have been mapped across Southeast Alaska. See the table of cumulative yellow-cedar decline, with the total acreage of aerially mapped decline by ownership type, geographic area, and National Forest Ranger District.

- Our partners are also conducting important work related to yellow-cedar:

- Benjamin Gaglioti and Daniel Mann (University of Alaska Fairbanks) collected tree cores from healthy, unhealthy, and dead yellow-cedar at Fick Cove on Chichagof Island. Study goals are to establish when tree growth impacts become evident in tree ring records and to identify drought indicators in wood cells associated with fine root loss. (2023)

- Forest Service Ecologists Sean Cahoon (PNW Research Station) and Kate Mohatt (Chugach National Forest) launched a project to document growth, mortality, and population characteristics of yellow-cedar at the northern edge of its range in Prince William Sound. (2023-2024)

Gavin McNicol and Max Berkelhammer (University of Illinois Chicago) and Benjamin Gaglioti and Hélène Genet (University of Alaska Fairbanks) received a grant from the U.S. Department of Energy Environmental System Science program to study the effects of yellow-cedar decline on coastal temperate rainforest biogeochemistry and biometeorology. They are coordinating site selection with local USDA-FS specialists Robin Mulvey, David D’Amore, and Jacqueline Foss. (2024-2025)

A managed stand on Kupreanof with abundant discolored yellow-cedar crowns from yellow-cedar decline fine root freezing injury.

(USDA Forest Service photo by Dr. Paul Hennon.)Young-growth yellow-cedar decline is an emerging issue, particularly where soils are wet or shallow. The problem was first observed in young-growth forests on Zarembo Island in 2012; before that, decline had only been observed in old-growth forests. To facilitate young-growth yellow-cedar decline monitoring, we compiled a database of 338 managed stands on the Tongass National Forest with yellow-cedar, but more remain to be added. Alongside the database, low-altitude aerial imagery and aerial detection surveys are used to identify stands with discolored tree crowns and suspected decline, which are then inspected on the ground. In 2023 and 2024, intensifying mortality and crown discoloration symptoms of decline were noted in several stands on Zarembo and Wrangell Islands through aerial detection and ground-based plots. To date, decline has been ground-verified in 33 young-growth stands on Zarembo, Kupreanof, Wrangell, Mitkof, and Prince of Wales Islands. Affected stands are typically 27- to 45-years-old, precommercial thinned between 2004 and 2012, and occur on sites with south to southwest aspects and wet or shallow soil.

A yellow-cedar crop tree on Zarembo Island impacted by yellow-cedar decline.

(USDA Forest Service photo by Robin Mulvey.)

In 2018, we installed 41 permanent plots in the five most severely affected stands on Zarembo, Kupreanof, and Wrangell Islands to quantify the impacts of yellow-cedar decline. The mortality rate for yellow-cedar was just 2% overall, yet far exceeded negligible mortality of associated tree species. All plots were remeasured in 2023 and 2024, and we found that 6% of yellow-cedar trees were dead, up from just 2% in 2018. The highest mortality rate was observed in the stand on Kupreanof Island, where the percentage of dead yellow-cedar trees increased from 8% in 2018 to 30% in 2024. A further 16% of the live yellow-cedar trees in our plots had pronounced crown discoloration symptoms and are not expected to recover.

Now that yellow-cedar decline is known to occur in young-growth stands, hydrology and soil temperature should be considered before precommercial thinning and other management activities occur, particularly in stands that are not expected to retain persistent snowpack in decades to come. Yellow-cedar planting sites should be carefully selected with both snowpack and deeper rooting depth in mind, promoting yellow-cedar where it is expected to thrive long-term.

Bioevaluation reports are available from work on young-growth yellow-cedar decline on Zarembo Island (Mulvey et al. 2013, updated 2015) and Kupreanof Island (Mulvey et al. 2015) and from our effort to quantify decline impacts in the most severely affected young-growth stands on Kupreanof, Wrangell and Zarembo Islands (Mulvey et al. 2019).

Yellow-cedar young growth database with the level of decline detected.

(USDA Forest Service map by Robin Mulvey)

Yellow-cedar decline functions as a classic forest decline and has become a leading example of the impact of climate change on a forest ecosystem. The term forest decline refers to situations in which a complex of interacting abiotic and biotic factors leads to widespread tree death, usually affecting one tree species or genus over an extended period of time. It can be difficult to determine the mechanism of decline, and the causes of many forest declines worldwide remain unresolved. Hennon et al. (2012) provide a detailed summary of the interdisciplinary research approach at multiple spatial and temporal scales that unraveled the complex causes of yellow-cedar decline.

Temporal patterns include the timing of yellow-cedar forest development and favorable climate (based on tree age), long-term linkages between climate patterns and pulses of decline, and fine-scale study of air and surface soil temperatures in research plots to identify temperature thresholds and mortality events. Most of the trees that have died within the last century, and continue to die, regenerated during the Little Ice Age (1400-1850). Heavy snow accumulation is thought to have occurred during this period, giving yellow-cedar a competitive advantage on low-elevation sites in Southeast Alaska. Trees on these sites are now susceptible to exposure-freezing injury under warmer climate conditions. An abnormal rate of yellow-cedar mortality began around 1880, accelerated in the 1970s and 1980s, and continues today. These dates coincide with the end of the Little Ice Age and a warm period in the Pacific Decadal Oscillation. On a finer temporal scale, recent analysis of 20th century weather station data from Southeast Alaska documented increased temperatures and reduced snowpack in late winter months, in combination with the persistence of freezing weather events in spring (Beier et al. 2008). From the time crown symptoms appear, it takes 10 to 15 years for trees to die, making it difficult to associate observations from aerial surveys to weather events in particular years. Mortality has subsided somewhat in the last three decades.

Spatial patterns of decline range from landscape level (latitude and elevation, patterns of snow persistence), to site level (mortality concentrated where hydrology or bedrock restricts rooting depth and snowpack does not persist in early-spring), to tissue level (sensitivity of yellow-cedar to freezing injury in spring). Recent mortality is most dramatic on the outer and southern coast of Chichagof Island (Peril Strait) and at higher elevations, indicating an apparent northward and upward spread that is consistent with the climate patterns believed to trigger mortality. At the southern extent of decline in Alaska (55-56° N), mortality occurs at relatively higher elevations, while farther north, decline is restricted to relatively lower elevations. Yellow-cedar forests along the coast of Glacier Bay and in Prince William Sound appear healthy, though small pockets of mortality have recently been detected in Glacier Bay National Park. These northerly parts of the range are presumably protected by deeper and more persistent snowpack. In 2004, a collaborative aerial survey with the British Columbia Forest Service found that yellow-cedar decline extended at least 100 miles south into British Columbia. Since that time, continued aerial mapping around Prince Rupert and areas farther south have confirmed more than 120,000 acres of yellow-cedar decline in BC.

Over 710,000 acres of decline have been mapped in Southeast Alaska through aerial detection survey since surveys began in the 1980s, with extensive mortality occurring in a wide band from the Ketchikan area to western Chichagof and Baranof Islands. The cumulative estimate includes forests mapped in the 1980s that were killed since the turn of the century. The hypothesis that has emerged is consistent with the observed patterns: conditions on sites with exposed growing conditions and inadequate snowpack in spring are conducive to premature root tissue dehardening, resulting in spring freezing injury to fine roots and gradual tree mortality. The temporal patterns help to explain why yellow-cedar occurs on many sites where it is currently maladapted. Yellow-cedar is protected by persistent snowpack and deeper soils.

See Sheila Spores' Alaska Yellow-Cedar Moves North (2009) for more insight.

Symptoms: Symptoms of yellow-cedar decline include yellow-red-brown foliage discoloration (affecting greater than 15% of the tree crown) and crown dieback, which results from damage to the fine roots. Root-freezing injury often kills individual trees slowly over more than a decade, causing the tree crown to gradually thin and discolor. Some trees remain alive for decades with only 5-10% of the original foliated tree crown, having lost most of the biological and ecological function of a live tree. Affected forests often contain trees at various stages of decline. Research on seasonal cold tolerance of yellow-cedar has demonstrated that yellow-cedar trees are cold-hardy in fall and mid-winter, but are highly susceptible to spring freezing. Yellow-cedar roots are more vulnerable to freezing injury, root more shallowly, and de-harden earlier in the spring than other conifer species in Southeast Alaska (Schaberg et al. 2005).

Associated Damage: Trees weakened by freezing injury may die rapidly if they are attacked and girdled by secondary bark beetles. Comprehensive assessment of pathogens and insects associated with declining trees found that Phloeosinus bark beetles (Phloeosinus cupressi) and Armillaria root disease play only minor roles in yellow-cedar mortality, attacking trees stressed by fine-root freezing injury (Hennon 1986, 1990a). Although it is not possible to see dead fine roots with the naked eye, it is possible to see dark-colored necrotic (dead) tissue moving up from dead coarse roots when the bark around the roots and root collar is removed.

Ecological Impacts: Yellow-cedar is an economically and culturally important tree. Yellow-cedar decline changes stand structure and composition (Oakes et al. 2014). Snags are created, and succession favors other conifer species. In some stands, where decline has been ongoing for up to a century, understory shrub biomass increases significantly. Nutrient cycling may be altered, especially with large releases of calcium as yellow-cedar trees die. The creation of numerous yellow-cedar snags is probably not particularly beneficial to cavity-nesting animals because its wood resists decay, but may provide branch-nesting and perching habitat. On a regional scale, excessive yellow-cedar mortality may lead to diminished populations (but not extinction). The loss of yellow-cedar in some areas may be balanced by increases in yellow-cedar in others, such as higher elevations and parts of its range to the northwest. Yellow-cedar is preferred deer browse, and deer may significantly reduce regeneration where their populations are high and spring snowpack is insufficient to protect seedlings from early-season browse.

A new study has been published that evaluated the economic returns and ecological impacts of salvage logging on forest succession (Bidlack et al. 2022). They found that small-scale salvage harvest did not impact forest succession or yellow-cedar abundance, and that economic returns were small to moderate but varied by location. Bidlack et al. also completed a final report on this topic in 2019.

Dr. Ben Gaglioti (University of Alaska- Fairbanks) and others used a dendrochronology approach to date when long-dead yellow-cedars had died alongside La Palouse Glacier. They estimated that all but one had been standing for more than a century (Gaglioti et al. 2021). It is unknown whether these very old mortality events at this location were caused by yellow-cedar decline or other factors related to glacial change.

Salvage recovery of standing dead yellow-cedar trees in declining forests can help produce valuable wood products and offset harvests in healthy yellow-cedar forests. Cooperative studies on mill-recovery and wood properties of yellow-cedar snags that have been dead for varying lengths of time (Kelsey et al. 2005) showed that all wood properties are maintained for the first 30 years after death. At that point, bark is sloughed off, the outer rind of sapwood (~0.6" thick) is decayed, and heartwood chemistry gradually changes. Decay resistance is altered somewhat due to these chemistry changes, and mill-recovery and wood grades are reduced modestly over the next 50 years. Remarkably, wood strength properties of snags are the same as that of live trees, even after 80 years. Localized wood decay at the root collar finally causes snags to fall about 80 to 100 years after tree death. The large acreage of dead yellow-cedar, the high value of its wood, and its long-term retention of wood properties suggest promising opportunities for salvage.

Appearance, characteristics, and mean time-since-death for the five dead tree (snag) classes of yellow-cedar (Hennon et al. 1990b).

(Hennon et al. 1990b)

See also: Yellow-Cedar Salvage Logging in Southeast Alaska: Case Studies Reveal Large Variation in Producer Efficiency and Profitability (Spores, 2019).

See the annotated bibliography of yellow-cedar (Hennon and Harris 1997), and Literature Cited sections of Hennon et al. (2016, 2012).

Click here for full list of yellow-cedar pubs (links to full text)

Hennon, P. E ; Harris, A. S. 1997. Annotated bibliography of Chamaecyparis nootkatensis. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-413. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 119 p. Available here.

Hennon, P. E.; D'Amore, D. V.; Schaberg, P. G.; Wittwer, D. T.; Shanley, C. S. 2012. Shifting climate, altered niche, and a dynamic conservation strategy for yellow-cedar in the North Pacific coastal rainforest. BioScience. 62: 147-158. Available here.

Hennon, P. E.; McKenzie, C. M.; D'Amore, D. V.; Wittwer, D. T.; Mulvey, R. L.; Lamb, M. S.; Biles, F. E.; Cronn, R. C. 2016. A climate adaptation strategy for conservation and management of yellow-cedar in Alaska. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-917. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 382 p. Available here.

Yellow Cedar Decline

United States Department of Agriculture

Prepared by

Forest Service Alaska Region

Leaflet

R10-TP-36

6/93

YELLOW-CEDAR DECLINE

Decline and mortality of yellow-cedar is the most spectacular forest problem in southeast Alaska. Yellow-cedar (Chamaecyparis nootkatensis), sometimes called Alaska-cedar, is the principal victim in this decline. Other tree species are largely unaffected. Yellow-cedar has extremely valuable wood; thus the problem has considerable economic impact. This tree species also has ecological importance and its wood and bark have long been used by Native people. Decline occurs in forests that have not been visibly altered by timber harvesting or other human disturbance. While the ultimate cause of yellow-cedar decline is still a mystery, this pamphlet provides information on the appearance of dying trees, describes the distribution of decline, highlights studies on possible disease organisms and ecological factors, and introduces ideas on possible causes.

Appearance of decline.

From a distance, forests suffering from yellow-cedar decline appear white or light grey due to the numerous dead trees (Fig. 1). These areas of dead trees can be as small as one acre or very expansive and contiguous covering miles along hillsides. A closer look reveals that most of the dead trees are yellow-cedars and even the ones that have been dead for many decades have pointed, unbroken tops. This appearance distinguishes them from other tree species which are more susceptible to wood decay and break off after being dead for a number of years. Yellow-cedar wood has a pleasant, characteristic smell that can be used to identify it long after tree death. On average, two-thirds of mature yellow-cedar trees are dead in areas of declining forests. Typically, declining yellow-cedar forests are composed of a dense concentration of dead yellow-cedars, some that died recently, others long ago; a smaller number of yellow-cedars that are currently dying; and some green trees of various species, including yellow-cedar (see cover photograph).

Declining cedar trees have a number of visible symptoms leading to death. Trees sometimes die quickly (e.g., 2-3 years) where crowns are full, but red or brown (Fig. 2). Other trees die much more slowly with crowns thinning for 15 years or more before death. Declining trees rarely, if ever, recover. Regardless of how rapidly crowns die, their root systems are always in an advanced stage of deterioration by the time crown symptoms appear. Death of the smallest roots is often the first indication that a tree is beginning to die of decline, followed by larger roots that die, and then death of inner bark in vertical streaks along the tree bole.

Once a cedar tree dies, it generally remains standing long after death, in some documented cases for more than a century!

Distribution of decline.

We have mapped the various locations of cedar decline from aircraft during the last decade (Fig. 3). More than 500,000 acres of decline have been identified in southeast Alaska. Decline is absent or not serious to the south in British Columbia or to the northwest towards the limits of yellow-cedar's range in Prince William Sound. Within southeast Alaska, the decline problem is common in forests where yellow-cedar is abundant on sites with poor moisture drainage at low or middle elevations. The common occurrence at remote and pristine locations indicates that cedar decline is a naturally-occurring phenomenon. Many of these areas are also visible from the air or water routes taken by tour ships or ferries where many people notice the poor condition of the forest and ask what's wrong.

Studies on disease organisms.

Our research has focused on organisms that are associated with dying cedars and could be the primary cause of tree death. We have found more than 50 species of fungi (Fig. 4), several insects and nematodes, and other organisms on dying cedars, but none has shown the capability of killing healthy seedlings or trees. Several fungi and bark beetles are weakly aggressive and probably speed the death of some trees, however. The primary cause now appears to be some non-living factor, probably associated with poorly drained soils.

In some areas, brown bears cause substantial damage to yellow-cedar trees each spring by tearing off the bark on their lower boles (Fig. 5). More than one half of cedars in some forests have this form of bole wounding, but its occurrence is independent from decline.

Ecological studies.

Our studies on the ecological aspects of cedar decline suggest that extensive tree mortality began a little over 100 years ago in about 1880. Our evidence also suggests that decline began at about the same time on all sites where it now occurs --thus it has not spread to any new sites since onset. The boundaries of decline have spread slightly at some sites, but typically by not more than 300 feet in the last century. Where decline has spread locally, its spread has been out of bogs (muskegs) upslope to trees growing on somewhat better drainage. Cedar decline is highly specific to certain sites, characterized by having poor drainage. Less commonly, cedar decline occurs on steeper hillsides where soils are very shallow and underlaid by bedrock. But yellow-cedar trees growing with other conifers on more productive sites with better drainage away from bogs have not experienced cedar decline. We predict that the problem will not develop in such forests.

The ages of most trees that die are in the range of 100-400 years old with some considerably older. These ages do not represent old age for a species such as yellow-cedar that has great potential longevity -- well over 1,000 years. We are currently studying the natural succession that is occurring on sites impacted with decline. As most of the yellow-cedar dies in the overstory while other tree species are less affected, yellow-cedar stands appear to be giving way to forests dominated by western hemlock and mountain hemlock.

Possible causes.

Our studies suggest that cedar decline is naturally-occurring and is caused by some environmental stress. Possible stresses include soil toxins and freezing damage. Organic toxins could result from natural anaerobic decomposition in the wet, highly organic soils where decline is so common. Perhaps yellow-cedar is more sensitive to such toxins.

Alternatively, cold temperatures could damage the fine root systems of yellow-cedar trees because roots are very shallow and are left unprotected during periods of frigid weather in winter when there is no snowpack to provide insulation. The onset of cedar decline coincided with the beginning of a warming trend in Alaska. Perhaps insulating snowpacks were more consistent at low elevations during winters 100 years ago before the climate warmed slightly changing more winter precipitation from snow to rain. More research is needed to test these ideas and to determine if associated climate change is responsible as a triggering mechanism. The lack of any contagious agent causing cedar decline suggests that foresters can have confidence in managing this valuable species without threat of it spreading to sites that do not already have decline.

Cedar Regeneration.

At most decline locations, yellow-cedar is not reproducing successfully. To replace yellow-cedars lost by the forest decline and timber harvesting, the Tongass National Forest has initiated a program of seed collection, seedling production, and planting. We have been studying the survival and growth of planted yellow-cedar seedings since 1986 on Etolin Island with the Wrangell Ranger District. When seedlings are planted in areas of adequate light and drainage, we found that they have excellent survival and early growth (Fig. 6). We are now experimenting with methods of attaining natural regeneration without planting by leaving mature trees as a source of seeds in harvested areas.

Conclusions.

There are different perspectives from which to think about yellow-cedar decline. One is the commercial loss and potential salvage opportunities of a very valuable tree species. Another is the loss of a tree that yields materials used by local people. The loss of yellow-cedar in declining forests may also represent a reduction in biological diversity as yellow-cedar gives way to the more common hemlock forests. Some biologists view cedar decline as the slow passing of one species from an ancient family of trees (the cedars and cypresses). Clearly, yellow-cedar decline is a naturally-occurring phenomenon --its early onset in about 1880 and occurrence in remote and pristine areas suggest that it has developed independently from human activities. As the story of yellow-cedar decline unfolds, it may provide a valuable lesson of the demise of a forest type under conditions where human involvement is minimal. Thus, it may help us to understand that forests are naturally dynamic and are always undergoing change even in areas largely unaffected by humans.

We are not alone in our efforts to try and solve the puzzle of forest decline. There are several dozen tree declines in different forests scattered all over the world; for almost all, scientists have not assigned adequate explanations as to their causes. Summarized below is some of what we do know about yellow-cedar decline.

- Covers more than 500,000 acres

- Occurs on wet poorly drained sites at lower and middle elevations

- Principle victim is yellow-cedar, a tree species which has ecological, cultural, and economic importance

- Many organisms are associated with dying cedars, but none is the primary cause

- Began about 100 years ago, apparently without subsequent long-distance spread

- Yellow-cedar is not reproducing effectively on many sites

- Some declining cedar forests are converting to hemlock-dominated forests

- Primary cause is still a mystery; researchers are currently investigating the role of soil and climate factors

Yellow-cedar decline

by Paul E. Hennon

Forest Pathologist, USDA Forest Service Alaska Region, State and Private Forestry

August 1993

Content prepared by Robin Mulvey, Forest Pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, robin.mulvey@usda.gov.