Discover History

The history of the Ozarks is long and rich. Remnants of many different eras exist today on the Forest, including historic Civilian Conservation Corp constructions, spring powered mills, and silver mines. Take a tour of Missouri's recent past by visiting one, some or all of the sites listed.

Cultural Resources are the physical remains of past human activity. They can be sites or districts and are prehistoric or historic-they must be at least 50 years old, but the oldest sites in North America are upwards of 12,000 years old. Cultural Resources are important reminders of the ways people have lived and coped with their world through time.

They offer us a glimpse into the past. The Mark Twain National Forest manages cultural resources within the Heritage Resources Program, a comprehensive program of responsibilities related to past human interaction with the land. The purpose is to protect historic properties (cultural resources), share their values with the American people, and contribute relevant information and perspectives to natural resource management.

Many of the cultural resources are fragile, non-renewable and their locations kept confidential. However, some historic properties on the forest are interpreted, to share their value and history with our forest visitors.

The Mark Twain has several sites that are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The National Register of Historic Places is the official list of the Nation's historic places (districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects) that are significant in American history and worthy of preservation. It is part of a national program to coordinate and support public and private efforts to identify, evaluate, and protect America's historic and archeological resources.

Additional information about them is located on the Missouri State Historic Preservation Office’s National Register website.

Archaeological sites on National Forest System Lands are protected by a number of federal laws, including the Antiquities Act of 1906, the Archaeological Resource Protection Act of 1979, and the Secretary of Agriculture’s Regulations. It is illegal to disturb, alter, remove, or damage archaeological sites and objects that are on Federal lands.

For more information on some of the cultural resources located on the Mark Twain National Forest, select the links below.

Historic Locations that are Now Recreation and Interpretive Sites

Boze Mill Float Camp

Boze Mill Spring forms a sparkling blue pool which produces between 12-14 million gallons of water per day. Aquatic plants add many shades of green to the spring branch. The historical 1880’s turbine and hand-layered rock wall from the Lucas Boze grist mill still exists. Boze Mill is nestled in a beautiful glen beside the Eleven Point River just above Riverton, and was once an important center of commerce where farmers could get wheat and corn ground into flour.

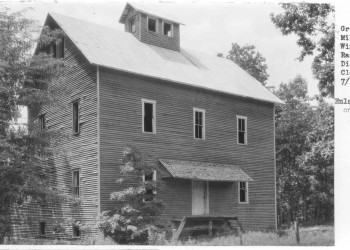

Greer Mill

First built in 1859, the gristmill was named for Captain Samuel Greer. The mill was destroyed during the American Civil War, and was rebuilt after the war. The mill changed hands several times until it ceased operation in 1922. The mill is still standing near the top of the east side of the gorge.

Falling Springs Picnic Area

The spring, known as Falling Spring because it pours out of the rock as a small waterfall, provided power for two mills. The second mill, which still stands, was built in the late 1920's. The water power was used to produce electricity, grind, corn, and make shingles. One of our most photographed areas, there is a wooden treadway to the old mill. Also located on the site is a log cabin over 100 years old.

Markham Springs and Fuchs House

This area gets its name from former owner, M. J. Markham, who acquired the property in 1901 and operated a lumber mill at the site until the 1930s. The Fuchs House, a five-bedroom concrete and native stone home, also sits on the property, along with a neighboring mill.

Located adjacent to the Black River, the recreation area contains a small pond that dates back to the 1800s.

Silver Mines Recreation Area

Silver Mines is located at a historic mining operation and is known for its Precambrian granite and felsite rocks. Silver Mines Recreation Area is named for the abandoned “Einstein Mine”, which was mined for Silver, Tungsten and Lead. The Einstein Silver Mining Company began mining in 1877, and mining ceased completely in 1946.

Ranger Station Historic Districts

Ava Ranger Station Historic District

The Ava Ranger Station Historic District is five frame and limestone buildings constructed by the Emergency Relief Administration (ERA) during 1936. The Pond Fork CCC Camp quarried the limestone used in the buildings and completed the landscaping around the buildings once they were completed. Very little of the buildings has been changed since their original construction in 1936.

Cassville Ranger Station Historic District

The Cassville Ranger Station Historic District was build by the Shell Knob CCC Camp in 1936. In addition to the five ranger district buildings, the CCC craftsman erected two stone carvings located to the east of the ranger's office.

Houston Ranger Station Historic District

The Houston Ranger Station Administrative Site was constructed during 1936-1937 by members of the Civilian Conservation Corps enrolled at the Lynchburg Camp (F-MO-15); the site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 4, 2003.

Winona Ranger Station Historic District

The Winona Ranger Station Historic District was constructed by the CCC in 1938 and 1939. The original ranger's office burned in 1957, and was replaced with a one-story frame building in 1960. The other four buildings, the dwelling, garage, warehouse and oil house, are much as they were when they were built. All of the original buildings are frame construction with wooden shingle siding. Buildings added in the 50's and 60's were designed to complement the original character of the district and also have wooden shingles.

Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears National Historic Trail was designated by Congress in 1987 in recognition of a significant chapter in American history, to remember and commemorate the survival of the Cherokee people despite their forced removal from their homelands in the Southeastern United States.

Over the winter of 1838-1839, the U.S. government removed at gunpoint most Cherokee Indians from their ancestral homelands and resettled them in Indian Territory west of Arkansas. The Cherokee round-up and removal were the most visible and publicized outcomes of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which authorized the relocation of nearly all eastern Indian tribes, including the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee Creek, and Seminoles.

In the case of the Cherokee, more than 15,000 people were systematically rounded up from their homes and held in detainment camps. They then were divided into detachments and forced to travel by foot, horseback, boat, and wagon across the southern U.S. to Indian Territory. More than 1,000 people died from exposure, illness, and exhaustion during the round-up and removal. The entire tragic event became known as the “Trail of Tears.”

The Cherokee traveled across water and land routes to reach their final destination in Oklahoma. The Water Route passes by Missouri along the Mississippi River in southeastern Missouri. The Northern Route, the Hildebrand Route, and the Benge Route are the three main land routes that cross Missouri. All three of these land routes pass through the Mark Twain National Forest.

Through all of the trials and tribulations encountered by the Cherokee during the removal process, the story of the Cherokee Trail of Tears is one of resiliency. Upon arrival in Indian Territory, the Cherokee reestablished their own system of government, and have managed to maintained their language, writing system, and tribal traditions for nearly 200 years.

The modern day descendants of the Cherokee are members Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma, as well as the Eastern Band of Cherokee, whose ancestors fled to the mountains of North Carolina during the forced removal.

Map of these routes in Missouri. In addition to the actual original Trail of Tears routes, there is an auto route across Missouri, so you can drive on modern highways that are located near, but generally not actually along, the original route.

Interpretive signs on the forest are located at Hazel Creek Recreation Area, the Potosi Ranger District Office, and the Mark Twain National Forest Headquarters in Rolla. To learn more about other locations in Missouri where the Trail of Tears is interpreted, visit the National Park Service website.

Learn more about the Trail of Tears by viewing the video produced by the National Park Service and the Cherokee Nation.

Surface varies with the section of the trail. The auto route through Missouri is asphalt, while most of the original route is unsurfaced, native material.