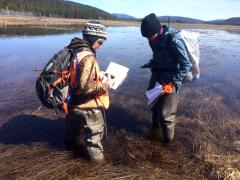

Picture an IMAX-style aerial film of a high-elevation wetland complex boasting every shade of green, from lime to emerald to olive, amid its vast landscape. Behind this image is Forest Service hydrologist Kyle Wright, his feet firmly on the ground, operating an unmanned aerial system or “drone” over this portion of Big Marsh in Oregon’s Little Deschutes River Basin.

Landscape restoration has a new aerial view thanks to this scientific tool. Drones, which have been used traditionally on fire management projects, are now telling important resource stories to help scientists inform other kinds of projects, from stream restoration to timber management.

“Drone use is a way to help tell our story for these projects so the public can better understand the actions that we are taking,” said Wright, district hydrologist on the Crescent and Bend Ranger Districts of the Deschutes National Forest. “This storytelling is going to be a proactive use of this technology, to share the actions that we are taking to protect resources and to restore our collective Forest Service land.”

Mapping, before and after a project, is used to document resource conditions, but drone footage adds details and paints a richer picture of conditions on the ground. Wright, who is also a UAS pilot for the Forest Service, said, “Drones have the advantage over other remote sensing techniques to acquire imagery at high resolution.”

On a summer day in July 2022, Wright flew a drone over the 2,250-acre Big Marsh to acquire footage for a forest partner—the Upper Deschutes Watershed Council—to document accomplishments. Wright has watched the footage multiple times to assess monitoring elements and each time the imagery’s beauty makes him pause, saying: “That is so cool.”

Central to the project’s purpose has been focus on one of the smaller marsh creatures—the Oregon spotted frog. The reddish-brown frog with black spots requires wetland habitats with a variety of water depths to support all its life stages. The aquatic frog is rarely found more than 6 feet from water.

Due to declines in population, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) listed it as a threatened species in 2014 and designated its critical habitat in 2016, per the Endangered Species Act. FWS created a seven-minute video to highlight its frog conservation efforts. Big Marsh is known to have one of the largest concentrations of the Oregon spotted frog, which ranges from northern California to the border with British Columbia.

Within the frog’s life cycle, adults move into shallow breeding sites to spawn as snow melts in the spring and then retreat to deep pools as water recedes in the fall. Frogs overwinter in pools where flow still occurs, oxygenating the water.

Carina Rosterolla, a wildlife biologist on the Crescent Ranger District, reflects on how the Forest Service strategically manipulated the ditches to allow flow across the marsh. “The main goal was to get the majority of water into the marsh, while creating, with some retention, over-wintering and breeding habitat,” she said.

Improving connectivity within the marsh improves the wetland ecosystem the frog needs for survival. Without it, shallow water can become disconnected, and egg masses can become stranded where hatchlings have nowhere to go. The project’s results have far surpassed what the scientists expected. “Overall water levels have increased, recharging areas of the marsh that have been dry for decades, as evident by the vegetation. There has been an increase in both over-wintering habitat and breeding habitat,” she said.

The wildlife biologist appreciates how drone footage shows if an area is ready to be surveyed or if more time is needed for snow melt. That timing is critical in documenting Oregon spotted frog data.

“We go out March through May and survey for egg masses,” she said. “Softball-size masses sit just below the surface of the water, often layered on top of each other. During some surveys, in prolific and warm areas, there can be around 200 egg masses.”

Other work toward restoring Big Marsh has included removal of reed canary grass, an invasive grass planted decades ago for cattle forage. In an effort to pinpoint its location, the Forest Service hired a contractor who flew a drone to map areas where reed canary grass was growing.

“The mapping of reed canary grass was extremely helpful to see how far it has spread and where pockets were,” Rosterolla said. “Using the imagery, the botanist knows where she needs to go to treat instead of wasting time searching for the areas.”

Wright is eager to fly a drone again over Big Marsh. This time he hopes to have camera sensors attached to take the temperature of the air, water, and — potentially — get imagery under the water. The Oregon spotted frog breeds in different areas depending on water level and water temperature. Thermally mapping the water could help scientists hone-in on breeding habitats to find where egg masses exist.

“Drone use has the potential to help us better monitor and evaluate our projects, and we’ll get there,” Wright said.