Why is Pollination Important?

Virtually all of the world’s seed plants need to be pollinated. This is just as true for cone-bearing plants, such as pine trees, as for the more colorful and familiar flowering plants. Pollen, looking like insignificant yellow dust, bears a plant’s male sex cells and is a vital link in the reproductive cycle.

With adequate pollination, wildflowers:

- Reproduce and produce enough seeds for dispersal and propagation.

- Maintain genetic diversity within a population.

- Develop adequate fruits to entice seed dispersers.

The Simple Truth: We Can’t Live Without Them!

Pollination is not just fascinating natural history. It is an essential ecological survival function. Without pollinators, the human race and all of earth’s terrestrial ecosystems would not survive. Of the 1,400 crop plants grown around the world, i.e., those that produce all of our food and plant-based industrial products, almost 80% require pollination by animals. Visits from bees and other pollinators also result in larger, more flavorful fruits and higher crop yields. In the United States alone, pollination of agricultural crops is valued at 10 billion dollars annually. Globally, pollination services are likely worth more than 3 trillion dollars.

- More than half of the world’s diet of fats and oils come from animal-pollinated plants (oil palm, canola, sunflowers, etc.).

- More than 150 food crops in the U.S. depend on pollinators, including almost all fruit and grain crops.

- The USDA estimated that crops dependent on pollination are worth more than $10 billion per year.

Environmental Benefits of Pollination

Clean Air (Carbon Cycling/Sequestration)

Flowering plants produce breathable oxygen by utilizing the carbon dioxide produced by plants and animals as they respire. Levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere have been rapidly increasing in the last century, however, due to increased burning of fossil fuels and destruction of vital forests, the “earth’s lungs.” Pollinators are key to reproduction of wild plants in our fragmented global landscape. Without them, existing populations of plants would decline, even if soil, air, nutrients, and other life-sustaining elements were available.

Water and Soils

Flowering plants help to purify water and prevent erosion through roots that holds the soil in place, and foliage that buffers the impact of rain as it falls to the earth. The water cycle depends on plants to return moisture to the atmosphere, and plants depend on pollinators to help them reproduce.

Reference: Flowering Plants, Pollinators, and the Health of the Planet (Marinelli, 2005): Plant. 2005. Janet Marinelli, Editor in Chief. First American Edition. Dorling Kindersley Limited (DK Publishing, Inc.). New York. 512 Pages.

Cultural Importance of Pollination

Native Peoples traditionally recognized the importance of pollinators:

- Cultural symbolism

- Food plants

- Medicinal plants

- Plant-based dyes

We explore only a few examples of culturally important pollinators or pollinated plants here. To learn more about culturally important plants and pollinators:

Cultural Symbolism

Butterflies

- Raven’s spokesperson - Haida (Pacific NW).

- Messenger (in dreams) from Great Spirit - Blackfoot.

- Earth’s fertility - Hopi “Bulitikibi” harvest dance.

- Flame, Teotihuacan (Palace of the Butterfly) - Ancient Mexicans (Olmecs, Toltecs, later Aztecs).

- Ancestor - Sumatra, Naga (Madagascar), Pima (N. America).

- Related to Morning Star - Arapaho, Mexecal.

Moths

- ‘Tun tawu = “goes in and out of fire” - Cherokee (North America).

- Symbol of knowledge, guardians of gold dust of eternity - Yaqui (Mexico).

- Powder - insanity (moth-crazy, sexual excess, incest, aphrodisiac) - Navajo (North America).

- Guardian of tobacco (caterpillar of Sphinx moth) – Navajo (North America).

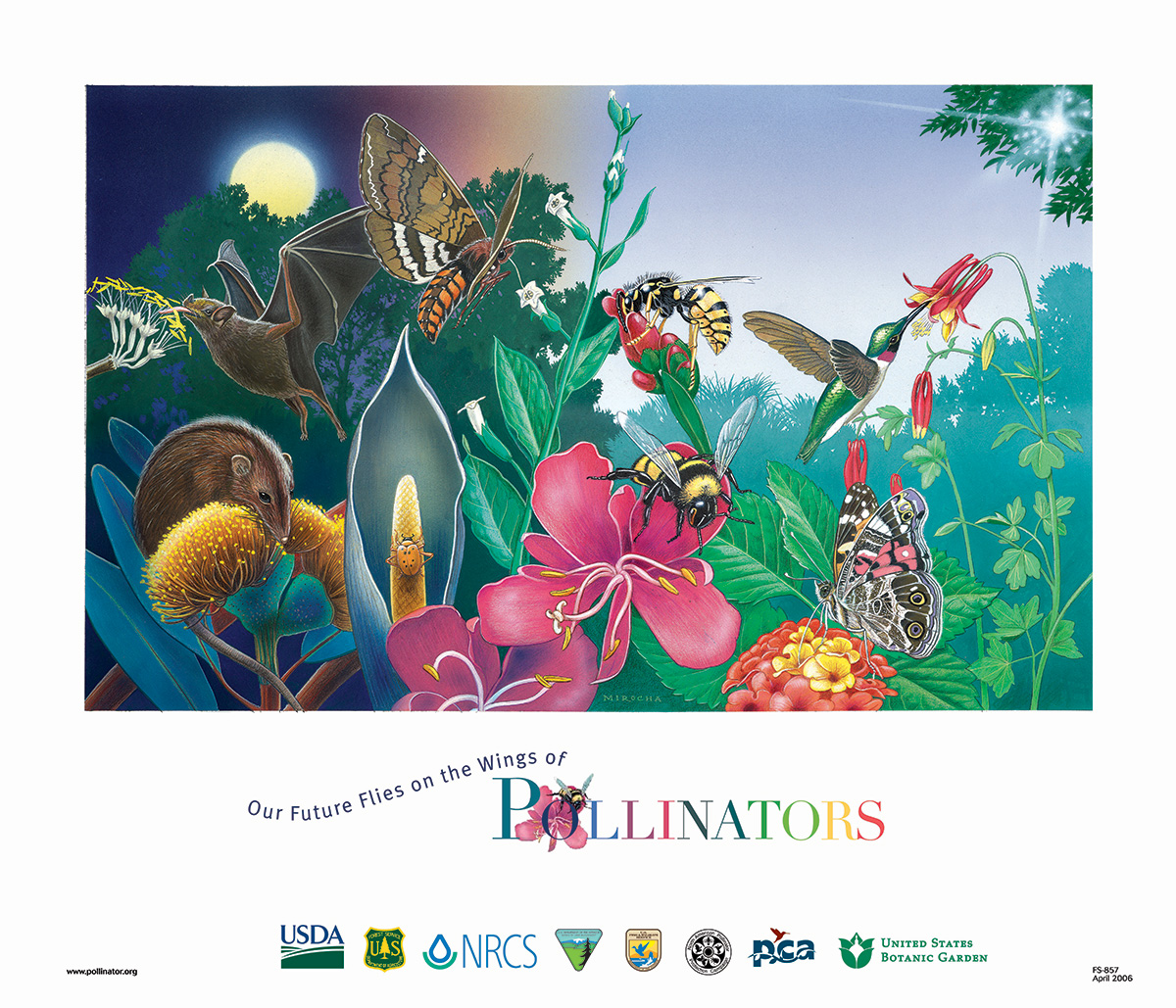

"Our Future Flies on the Wings of Pollinators"

This poster is made available by the U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Land Management, Natural Resources Conservation Service, U.S. Botanical Gardens, and the NAPPC (North American Pollinator Protection Campaign).

Artist: Paul Mirocha

Plant Pollination Strategies

Plant Pollination Strategies

Pollination occurs when birds, bees, bats, butterflies, moths, beetles, other animals, water, or the wind carries pollen from flower to flower or it is moved within flowers. The successful transfer of pollen in and between flowers of the same plant species leads to fertilization, successful seed development, and fruit production. Other factors such as drought, extreme temperature shifts, or diseases may prevent full fruit and seed production. For more information, also see The Birds and the Bees.

Morphological Adaptation

Flowering plants have co-evolved with their pollinator partners over millions of years producing a fascinating and interesting diversity of floral strategies and pollinator adaptations. The great variety in color, form, and scent we see in flowers is a direct result of the intimate association of flowers with pollinators. The various flower traits associated with different pollinators are known as pollination syndromes. Flowering plants have evolved two pollination methods: 1) pollination without the involvement of organisms (abiotic), and 2) pollination mediated by animals (biotic). About 80% of all plant pollination is by animals. The remaining 20% of abiotically pollinated species is 98% by wind and 2% by water.

Wind

Plants that use wind for cross-pollination generally have flowers that appear early in the spring, before or as the plant's leaves are emerging. This prevents the leaves from interfering with the dispersal of the pollen from the anthers and provides for the reception of the pollen on the stigmas of the flowers.

In species like oaks, birch, or cottonwood, male flowers are arranged in long pendant catkins or long upright inflorescences in which the flowers are small, green, and grouped together, and produce very large amounts of pollen. Pollen of wind-pollinated plants is lightweight, smooth, and small.

Plants that are wind pollinated generally occur as large populations so that the female flowers have a better chance of receiving pollen. For more information, see Wind and Water Pollination.

Water

The small percentages of plants that are pollinated by water are aquatic plants. These plants release their seeds directly into the water. For more information, see Wind and Water Pollination.

Animals

Flowering plants and their animal pollinators have co-evolved where the forces of natural selection on each has resulted in morphological adaptations that have increased their dependency on one another. Plants have evolved many intricate methods for attracting pollinators. These methods include visual cues, scent, food, mimicry, and entrapment.

Likewise, many pollinators have evolved specialized structures and behaviors to assist in plant pollination such as the fur on the face of the black and white ruffed lemur or a bat. Animal pollinated flowering plants produce pollen that is sticky and barbed to attach to the animal and thus be transferred to the next flower.

Flowering Time

Plants have evolved differing flowering times that occur throughout the growing season to decrease competition for pollinators and to provide pollinators with a constant supply of food. From the first hints of warmth in late winter through spring and summer, until last call in autumn, flowering plants are available to their pollinators providing pollen and nectar in exchange for the pollination service.

in autumn, flowering plants are available to their pollinators providing pollen and nectar in exchange for the pollination service.

February: skunk cabbage.

Photo by Charles Peirce.

March-May: white trillium.

Photo by Charles Peirce.

March-May: red columbine.

Photo by Larry Stritch.