Crop Wild Relatives

What are crop wild relatives?

A crop wild relative is a plant species occurring in the "wild" that is the congener (species from which the crop was domesticated) or a closely related species (in the same genus) to a particular domesticated crop species. Crop wild relatives may contribute genetic material to the crop species, which may provide for increased disease resistance, fertility, crop yield or other desirable traits. Almost every species of plant that we humans have domesticated and cultivate has one or more crop wild relatives.

Plant characteristics that are valuable to humans are selected for by breeding those that show these characteristics. During the process of domestication, changes occur in the genes (genotype) of the plant. How the plant looks on the outside (phenotype), and some of its internal processes are altered.

Plants are modified through cultivation to suit our needs. When we find a cultivar with characteristics we like such as the color, taste, or texture, we maintain it though cultivation. Occasionally we abandon use of the crop wild relatives and in most cases, this ancestor continues to grow in the wild.

For a list of some of the native species of crop wild relatives and wild utilized plants found in the United States, see Native Crop Wild Relatives of the United States Related to Food Crops (PDF, 172 KB).

Grapes

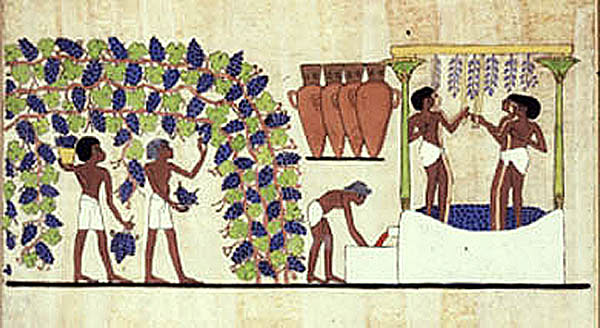

Grapes are one of the oldest cultivated plants, initially cultivated in the Mediterranean area and spreading across Europe and Asia, for which the wild relative still exists. Scientists have found grape vine fossils over 60 million years old. Humans have used grapes for food and wine since the earliest times.

The wild crop relative of grapes used in wine making came from only one species Vitis vinifera native to the Mediterranean and Asia. Most of the other 50 or so grape species in the world are from North America. Early French colonists in Florida tried many times to introduce and successfully establish Vitis vinifera vineyards. Each time there was a complete crop failure and these failures were repeated many times in colonial America. These early French viticulturists never discovered the cause of the crop failure.

American botanists and naturalists were sending many different species of North American grapes to Europe, especially France. Viticulturists were developing numerous horticultural cultivars. In the mid to late 1850s and the early 1860s, thousands of North American grape vines where being shipped to Europe. A North American aphid, the grape phylloxera, made its way to Europe by 1863. The grape phylloxera attacked Vitis vinifera in a manner never observed on North American grape species. On most North American grape species, this aphid feeds on grape leaves forming galls. In Europe, the grape phylloxera attacked Vitis vinifera by feeding on its small roots. The aphid injects saliva into the roots and then sucks up the sap. The aphid’s saliva is toxic to Vitis vinifera. However, the mystery of why the grapes were dying was not discovered until 1868 when Professor Planchon and his colleagues dug up healthy, dying, and dead Vitis vinifera vines. On the “healthy” vines, they discovered grape phylloxera attached to the roots. It was discovered that by the time the vines were observed dying the aphids had already moved on to their next meal. By this time, nearly 40 percent of French vineyards had been destroyed. Eventually, it was discovered that grafting Vitis vinifera scions on to the phylloxera resistant rootstock of the American species Vitis riparia that the grape phylloxera was defeated.

By the late 1870s and 1880s it was generally accepted that grafting Vitis vinifera scions onto an American rootstock, Vitis riparia was the “cure” to keeping Vitis vinifera vines alive, healthy and productive. Thus began the tremendously large and expensive program of reconstituting all the grape vines in France and other European countries by grafting Vitis vinifera cultivars on to Vitis riparia rootstock.

Today, populations of Vitis riparia are managed in situ (in place) throughout its range in the United States to maintain its genetic diversity so that when called upon again scientists will have a crop wild relative to draw upon.

Winemaking in ancient Egypt: grapes were harvested and the juice pressed by stomping. Photo courtesy Purdue Horticulture & Landscape Architecture.

Winemaking in ancient Egypt: grapes were harvested and the juice pressed by stomping. Photo courtesy Purdue Horticulture & Landscape Architecture.

Fun Fact

In the book, “The Great Wine Blight” the author George Ordish points out that there was a Spanish decree from 1524 that required all grape vine cuttings from Spain to be grafted onto native rootstocks in Mexico to bring the vines to maturity sooner.

There are thousands of varieties of grapes! Photo courtesy Forestry Images.

There are thousands of varieties of grapes! Photo courtesy Forestry Images.

Cotton

Cotton (Gossypium spp.) grows in warm countries around the globe. Asian cotton originated in Africa and India and was cultivated for over 5,000 years. In the 1500s, explorers discovered that cotton plants were also being grown and used in the Americas.

The American cotton had longer fibers and was easier to spin into thread. Because of this, it was re-introduced back to Africa where it replaced traditional cultivars. Further domestication modified the cotton plant from its wild relative.

Cotton plants were cultivated to get the longest, softest fibers for making cloth. Photo by Howard F. Schwartz, Colorado State University.

Cotton plants were cultivated to get the longest, softest fibers for making cloth. Photo by Howard F. Schwartz, Colorado State University.

Cotton boll. Photo Wikipedia, Public Domain.

Cotton boll. Photo Wikipedia, Public Domain.

Did you know?

- The white fibers attached to the cottonseed that are spun together to make thread are each a single cell.

- The USDA began a cotton-breeding program in 1910 on the Gila River Pima Indian Reservation in Sacaton, Arizona and developed the luxurious, long-fiber cotton now famous worldwide as “Pima” cotton.

Filberts (Hazelnuts)

European Filberts or hazelnuts (Corylus avellana) are larger and have thinner shells than their North American cousins, beaked hazelnut (C. cornuta) and American hazelnut (C. americana). However, the European hazel is less cold hardy and is susceptible to “filbert blight”. Plant breeders have worked to crossbreed the best qualities of the European to its American cousins. This has produced a superior hazelnut cultivar that is resistant to the filbert blight.

The European/Turkish hazelnut or filbert (Corylus avellana). Photo courtesy Forestry Images.

The European/Turkish hazelnut or filbert (Corylus avellana). Photo courtesy Forestry Images.

The American Hazelnut (Corylus americana) is hardier than the European. Photo courtesy Forestry Images.

The American Hazelnut (Corylus americana) is hardier than the European. Photo courtesy Forestry Images.

Corylus avellana ripe nuts. Photo Simon A. Eugster, Wikipedia [CC BY-SA 3.0].

Corylus avellana ripe nuts. Photo Simon A. Eugster, Wikipedia [CC BY-SA 3.0].

Oregon and Washington produce almost all the filberts in the United States. Would you like to raise a crop straight from a wild relative? Find out how to obtain and grow your own delicious hazelnuts. See the National Arbor Day Foundation's publication, Hybrid Hazelnuts: An Agroforestry Opportunity (PDF, 1.0 MB).

Chiltepin Pepper: “the mother of all peppers"

A small, fiery, round pepper native to Mexico known as chiltepin (Capsicum annuum) is the single wild relative of hundreds of sweet or hot pepper varieties found in grocery stores today (jalapeno, poblano, mirasol, cayenne, bell, and others). Habanero and Tabasco are two peppers that did not originate from chiltepin.

Chiltepin are the oldest as well as the hottest wild pepper in the Americas. They grow on the rocky surfaces of steep slopes and are difficult to find because they grow in among other shrubs.

- The Coronado National Forest in Arizona has reserved 2,500 acres in the “Wild Chile Botanical Area”, that provides habitat for the largest population of chiltepin chile peppers (Capsicum annuum var. glabrisculum) north of Mexico.

- Birds cannot taste the hotness in peppers and they eat the fruits whole. Birds that eat many peppers are distasteful to predators!

- The Tarahumara Indians of the Sonoran Desert in Mexico believe that chiltepin were the greatest protection against the evils of sorcery. One of their proverbs holds, “The man who does not eat chile is immediately suspected of being a sorcerer.”

- There is a “heat index” for peppers measured in Scoville Heat Units starting at zero Scoville units for Bell Peppers. The “ghost pepper” of northeastern India was the hottest pepper on record for many years measuring 1,000,000 Scoville units. This record has been surpassed more than once by peppers developed in Australia and South Carolina measuring over 2 million Scoville units! How hot can it get? Pepper spray used by police weighs in at 2 million Scoville units.

- An ounce of chiltepin peppers sells for over five dollars in the United States. There is a great demand for these peppers, a demand that can exact its toll on wild populations.

Chiltepin pepper (Capsicum annuum) fruits are tiny but pack a punch! In Mexico, they are also called “chile” and sometimes “bird peppers”. Photo by Michael (trekr) on Flickr.

Chiltepin pepper (Capsicum annuum) fruits are tiny but pack a punch! In Mexico, they are also called “chile” and sometimes “bird peppers”. Photo by Michael (trekr) on Flickr.

These jalapeno peppers were domesticated from the chiltepin pepper. Photo courtesy Mountain Meadow Seeds.

These jalapeno peppers were domesticated from the chiltepin pepper. Photo courtesy Mountain Meadow Seeds.

Cranberries

Native to North America, Europe, and parts of Asia, cranberries have not changed much from their wild relatives. Cranberries grow on low-trailing vines in sandy or peat marshes. Because cranberries, float, their marshes are flooded with water to aid harvesting. Some cranberry beds are over 100 years old and still producing! Native Americans discovered the wild cranberry's versatility as a food, fabric dye, and healing agent.

American and Canadian sailors on long voyages knew they could eat cranberries to protect themselves from scurvy; making them a cranberry counterpart to British “limeys.” Though early sailors did not know about vitamins, what protected them was the high level of vitamin C in the cranberries. The fruit is also high in vitamin A, potassium, and antioxidants.

- Small pockets of air inside the berry cause the cranberry to bounce and to float in water. Because of this, when the marsh is flooded, the berries float to the surface and can be gathered for harvest.

- Native Americans pounded cranberries into a paste and mixed with dried meat, and called this mixture “pemmican.”

- More than 94% of Thanksgiving dinners include cranberry sauce.

Cranberries cut open to show air pockets inside the fruit. Photo courtesy Wisconsin State Cranberry Growers Association.

Cranberries cut open to show air pockets inside the fruit. Photo courtesy Wisconsin State Cranberry Growers Association.

Cranberries grown commercially in large beds are harvested by flooding the field. Photo courtesy Wisconsin State Cranberry Growers Association.

Cranberries grown commercially in large beds are harvested by flooding the field. Photo courtesy Wisconsin State Cranberry Growers Association.

Cranberries are gathered with booms and rakes. Photos courtesy Wisconsin State Cranberry Growers Association.

Cranberries are gathered with booms and rakes. Photos courtesy Wisconsin State Cranberry Growers Association.

Complementary Conservation of Wild Cranberry

Wild cranberries, from which cultivated cranberries are derived, have been chosen as the first test case for a program to conserve the crop wild relative both in their natural environments (in situ) and in gene banks (ex situ) where they are available for use in research, breeding, and restoration. The large-fruited cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) is the commercially important species, while the small cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccos) is a close relative. The wild populations contain genetic diversity that may not be found in the cultivated varieties and could be important in breeding new varieties that can adapt to a changing climate and other environmental stresses.

Read more about complementary conservation of wild cranberry…

Sugar cane

Long ago, honey was the only sweetener in the countries beyond Asia, and all visitors to India were taken with the “reed which produced honey without bees”. What was that reed? Sugar cane was the reed.

Sugar cane (Saccharum spp.) is a tall grass that looks rather like bamboo. It was known in New Guinea for thousands of years. Sugar cane spread along human migration routes to Asia and India. Here it was crossbred with some wild sugar cane relatives to produce the commercial sugar cane we know today.

Explorer Christopher Columbus transported sugar cane from the Canary Islands to what is now the Dominican Republic in 1493. The crop was taken to Central and South America from the 1520s onwards, and later to the British and French West Indies.

Raw sugar.

Raw sugar.

Molasses.

Molasses.

- Brown-colored raw sugar is what is left when juice from the sugar cane is dried.

- In the 1400s in India, cows belonging to the Sultan of Mandu were fed sugar cane for weeks to make their milk sweet for use in puddings.

- Sugar cane juice is boiled down into a syrup called molasses.

- In 1919, “The Boston Molasses Disaster” tragically killed 21 people when a huge tank of molasses split open. It took weeks to clean up the sticky mess.

Conservation

It is important that we maintain our crop wild relatives. They contain genetic variability that may be crucial in the future.

Ethics in Plant Collecting in the Wild

Any plant that has value can be at risk for over-harvest. If you plan to pick things in the wild please follow these basic rules:

- Never collect all of the specimens in an area; take no more than 10%.

- If it is unusual or rare, leave it alone.

- Ask permission to pick or dig anything.

See Ethics and Native Plants for more information about plant collection.

Joint Strategic Framework on the Conservation and Use of Native Crop Wild Relatives in the United States

Recognizing the value of crop wild relatives (CWR) of native plants for crop improvement and providing for the current and future food security of the United States and the world, the Forest Service and Agricultural Research Service, agencies of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), developed a strategic framework for collaboration that will help ensure the conservation, evaluation, and use of native CWR occurring on National Forest System lands.

See the publication (PDF, 1.3 MB)…

For More Information

- Complementary Conservation of Wild Cranberry

- USDA Forest Service and Agricultural Research Service Crop Wild Relatives Partnership Projects: The Importance of Research Natural Areas, Wilderness Areas, and More (PDF, 224 KB)

- Native Crop Wild Relatives of the United States Related to Food Crops (PDF, 172 KB)

- Northern Research Station Research Natural Areas (RNAs)

- USDA Forest Service and Agricultural Research Service (ARS) Collaboration on the Conservation of Crop Wild Relatives (PDF, 3.3 MB) - a presentation by Karen A. Williams, USDA ARS.