Paradise Lost

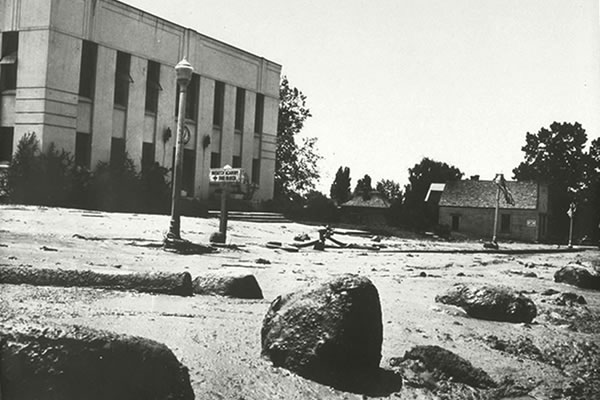

Loss of topsoil on the Wasatch Plateau.

Loss of topsoil on the Wasatch Plateau.

“A wild natural region…a perfect flower garden" is how famed naturalist Henry Fairfield Osborn described Utah's subalpine Tall Forb meadows when he first visited the area in 1877. To his dismay, by 1904 the same mountain landscape had been substantially degraded into "the most thoroughly devastated country I know of…”

Migration and Settlement

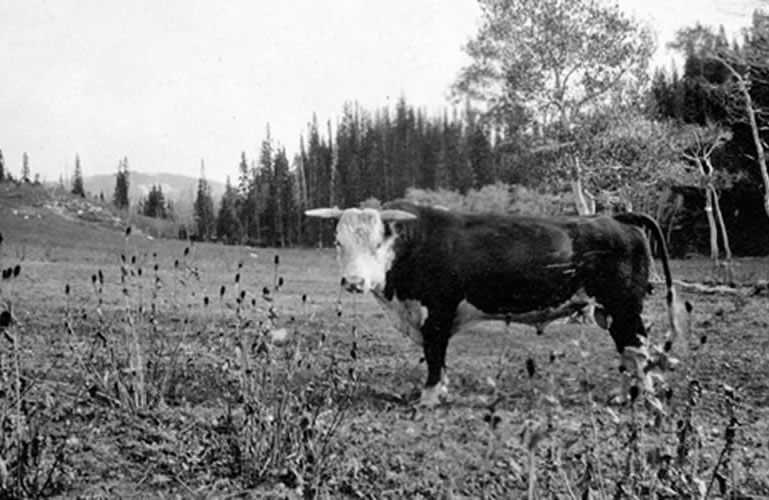

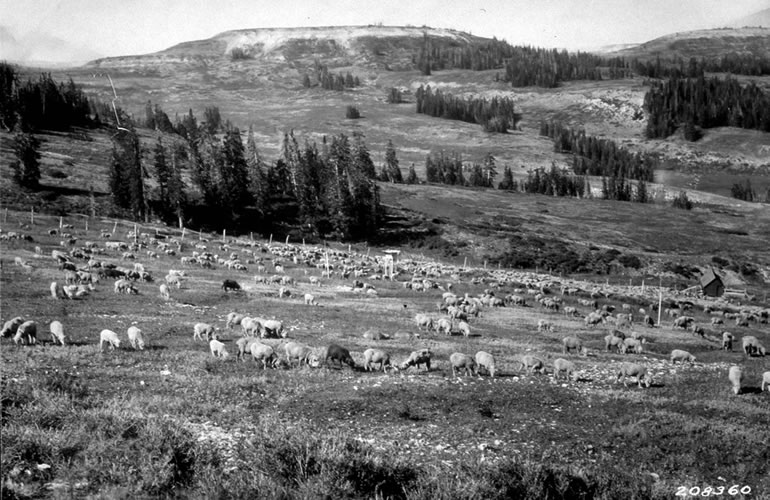

When settlers first came into the western mountains of the United States during the mid-1800s, they encountered a young land with an abundance of lush pastures available for grazing domestic animals. Not long after, as arable lands became rapidly settled and put into domestic production, many farmers turned to ranching and the raising livestock. Large numbers of cattle and sheep were herded into the mountains and spent their summers grazing on the high Wasatch Plateau's seemingly inexhaustible flower-filled pastures. It is estimated that between 1887 and the early 1900s, nearly two and a half million cattle and sheep had grazed atop Utah's high elevation rangeland plateaus. Sadly, within a short span of 50 years many of the pristine mountain forb lands became so heavily overgrazed and degraded that the bloom from the western range had mostly vanished.

Without protective cover provided of the tall, native forb species the rich, fertile topsoil became rapidly lost, resulting in severe erosion throughout the Wasatch Plateau. Subsequently, frequent and torrential summer thunderstorms washed away mountains of topsoil and regularly flooded the valley towns of Manti, Ephraim, Mt. Pleasant, and many others located below the plateau Rim. Between two and four feet of topsoil eroded or was scoured off the mountaintops in many areas, according to some accounts. Consequently, by the turn of the century over half of the Tall Forb sites became permanently lost.

Many luxuriant tall forb species disappeared from the landscape by the late 1890s or became rapidly replaced by grasses and plants adapted to dryer, poorer soil conditions such as mule's ear (Wyethia amplexicaulis), low larkspur (Delphinium nelsonii) or worse yet, by weedy, annual species like mountain tarweed (Madia glomerata). Ecologists today consider the few, original pristine remnant Tall Forb sites to be among the rarest plant communities in the Interior West.

Effects of Settlement of the West

When gold was discovered in California in the late 1840s, large numbers of people surged into the West. With further successive migrations and increased settlement of Mormon pioneers into the Interior West, it took less than 50 years for the mountains to become overrun by vast numbers of cattle and sheep.

Throughout the Wasatch mountains and high plateau country livestock were herded into the mountains for their bountiful summer ranges. Unfettered sheep and livestock grazing combined with intense summer thunderstorms resulted in deteriorated watersheds causing great flood damage and large-scale soil loss, devastating villages and towns below the rim.